- Invertebrates

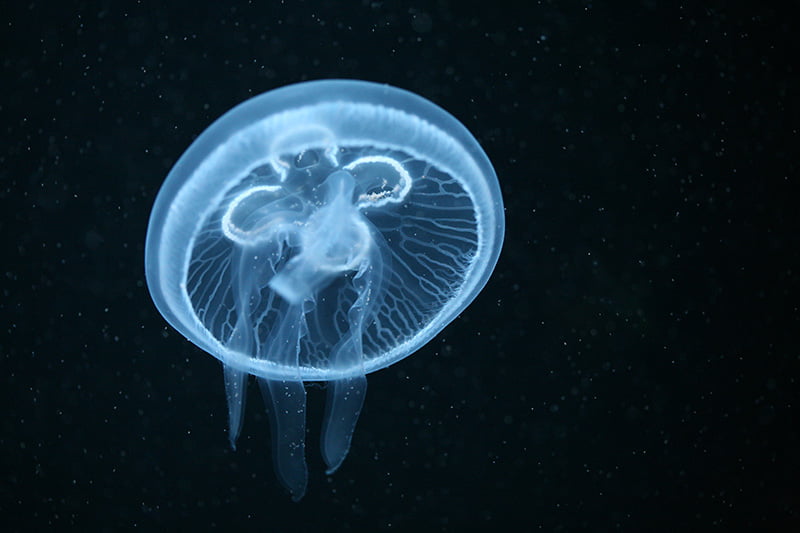

Jellies

Learn more about these ancient drifters of the sea!

Jellies have been around for hundreds of millions of years—since before dinosaurs roamed the Earth. They’re members of the phylum cnidaria, pronounced NYE-daria, from the Greek word for “stinging nettle.” Members of this group of invertebrates, meaning animals without backbones, have stinging capsules in the tentacles surrounding their mouths.

There are over 2,000 known jelly species worldwide, and scientists believe many more remain to be discovered. Here at the Aquarium, we have three jelly species in our care: moon jellies, commonly found in cooler, temperate waters like those of the Salish Sea; and two species found in the warmer, tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific—spotted lagoon jellies and upside-down jellies.

At the Aquarium

- Moon jelly habitat, Pier 59

- Jelly nursery and At Home in the Ocean habitat, Ocean Pavilion

A big, fascinating family

Jellies are related to a lot of interesting creatures, many of which can also be found at the Seattle Aquarium: sea anemones, sea pens, sea fans, sea whips, and soft and stony corals, to name just a few.

Jellies are plankton, really?

Many people think of plankton as microscopic creatures but they’re actually defined by their inability to swim against the current: they’re drifters and floaters. While jellies can pulsate their bells to move, the force isn’t strong enough to propel them against the current. So not only are jellies plankton, they’re the very largest form of plankton on Earth.

The mouth is also the…ewww!

It’s true: a jelly’s mouth also serves as its anus. That means they take in food—mostly plankton, crustaceans, fish eggs, small fish and even other jellies—and poop out waste through the same opening. Here’s another interesting fact: jellies are made up of 98% water. If they get washed up on the beach on a warm and sunny day, they can literally evaporate to almost nothing!

That said, if you happen upon a jelly on the beach, it’s best to leave it alone. It’s likely already dead—and can still sting. Jellies are also an important part of the food web for birds, crab and other scavenging animals.

About those stings

All jellies carry a sting—it’s what defines them as cnidarians. But the severity of that sting varies greatly from species to species. For instance, the sting of a box jelly, found in the waters around eastern Australia, can kill an adult human in less than three minutes!

None of the jelly species in our care are very dangerous but their stings can still cause pain and irritation. If you encounter a moon jelly in the waters of Puget Sound or are lucky enough to snorkel with spotted lagoon or upside-down jellies in the Coral Triangle, stay on the safe side and don’t touch them.

A mirror image

Another fascinating fact: jellies have what’s called radial symmetry. That means that if a jelly was divided through the center and across the bell in any direction, the two halves would be exactly the same.

You can make a difference for jellies everywhere

It starts with small, everyday choices. For example, using reef-safe sunscreen helps prevent damage to delicate marine ecosystems where jellies and other marine animals make their homes. And reducing use of fertilizers and pesticides helps keep chemicals out of the ocean. Interested in more ideas? Visit our Act for the Ocean webpage!

Quick facts

Jellies have been around since before dinosaurs roamed the Earth!

Jellies are the largest form of plankton.

These invertebrates have stinging capsules in the tentacles surrounding their mouths.