The densest fur of any animal on Earth: All about sea otters

How many hairs do you have on your head? Most humans have about 100,000, give or take a few. But sea otters have anywhere between 500,000 and 1,000,000 hairs per square inch of skin—meaning that one inch of a sea otter’s fur has between five and 10 times the number of hairs you have on your entire head!

Would you like fries and a shake with your 160 burgers?

Sea otters need their thick fur to keep warm because, unlike marine mammals such as harbor seals, they don’t have a blubber layer. Instead, they rely on their fur and extra-high metabolisms to do the job.

Those metabolisms require a lot of fuel, which leads us to another amazing sea otter fact: they eat about 25% of their body weight every day. (Think of your body weight. That’s how many quarter-pound burgers you’d need to eat, each and every day, to keep up with a sea otter! Put another way, a person weighing 160 pounds would need to eat roughly 40 pounds of food a day—can you imagine?)

Imagine eating 25% of your body weight every single day! Sea otters make it look pretty fun, don’t they?

Ecosystem superstars

Unfortunately, that dense fur is the reason that sea otters in the Pacific Northwest were hunted to extinction at the turn of the 19th century. The good news is that they’re now protected from hunting. And, after a repopulation effort in the 1960s, when many otters were collected from Alaska and re-released off the coast of Washington, they’ve made a recovery in our state.

That’s not just a good thing for the otters, it’s good for the entire ecosystem. Sea otters are what’s called a keystone species, which means they help hold the entire ecosystem together, and without them, the ecosystem would change drastically—and not in a good way. For instance, sea otters in the wild eat a lot of sea urchins. Sea urchins eat kelp, among other things. Without otters eating the urchins, there would be less kelp. And kelp forests provide a critical habitat for all kinds of animals, including endangered orcas, salmon and pinto abalone.

Bonus reading: Our research team monitors populations of key species, including sea otters; learn more on our marine populations webpage.

Check out this video of researchers, including folks from the Seattle Aquarium team, monitoring the sea otter population and ecosystem health on a spectacularly beautiful day along Washington’s outer coast.

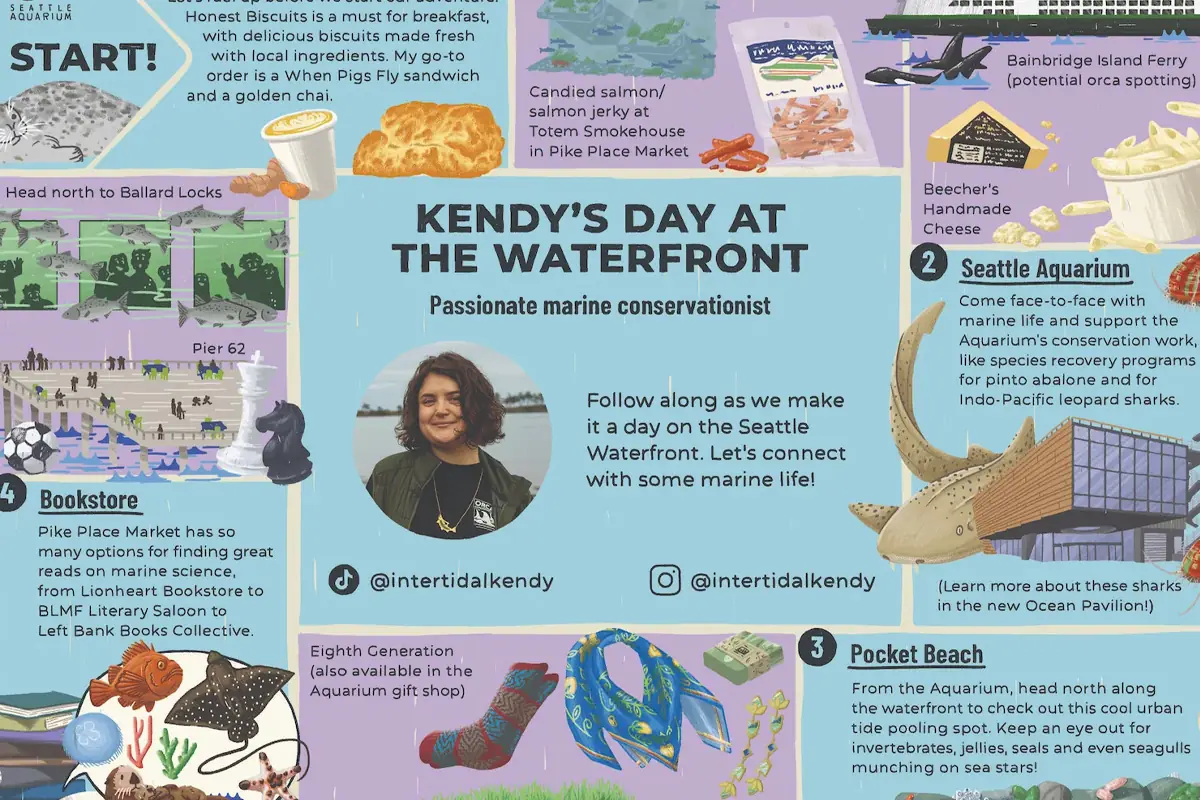

Come say hello to Sekiu and Mishka!

We have two female sea otters in our care at the Seattle Aquarium: Sekiu, who was born right here in 2012; and Mishka, who came to us in 2015 after being caught in a fishing net as a young pup and being deemed non-releasable by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (Another fast fact: every bird and mammal in our care was either born in a zoo or aquarium or rescued and deemed non-releasable—you can read more on our animal wellbeing page).

Want to learn more about sea otters? Explore our sea otter webpage. Better yet, plan a visit to the Seattle Aquarium to see Sekiu and Mishka in person! You can also make a difference for them, and for sea otters everywhere, by taking action on behalf of the marine environment. Even small changes can help the otters, their habitat and the one world ocean we all depend on. Explore our take action page to get started!

Mishka and Sekiu enjoying some well-earned relaxation after a day full of playing, eating and grooming.