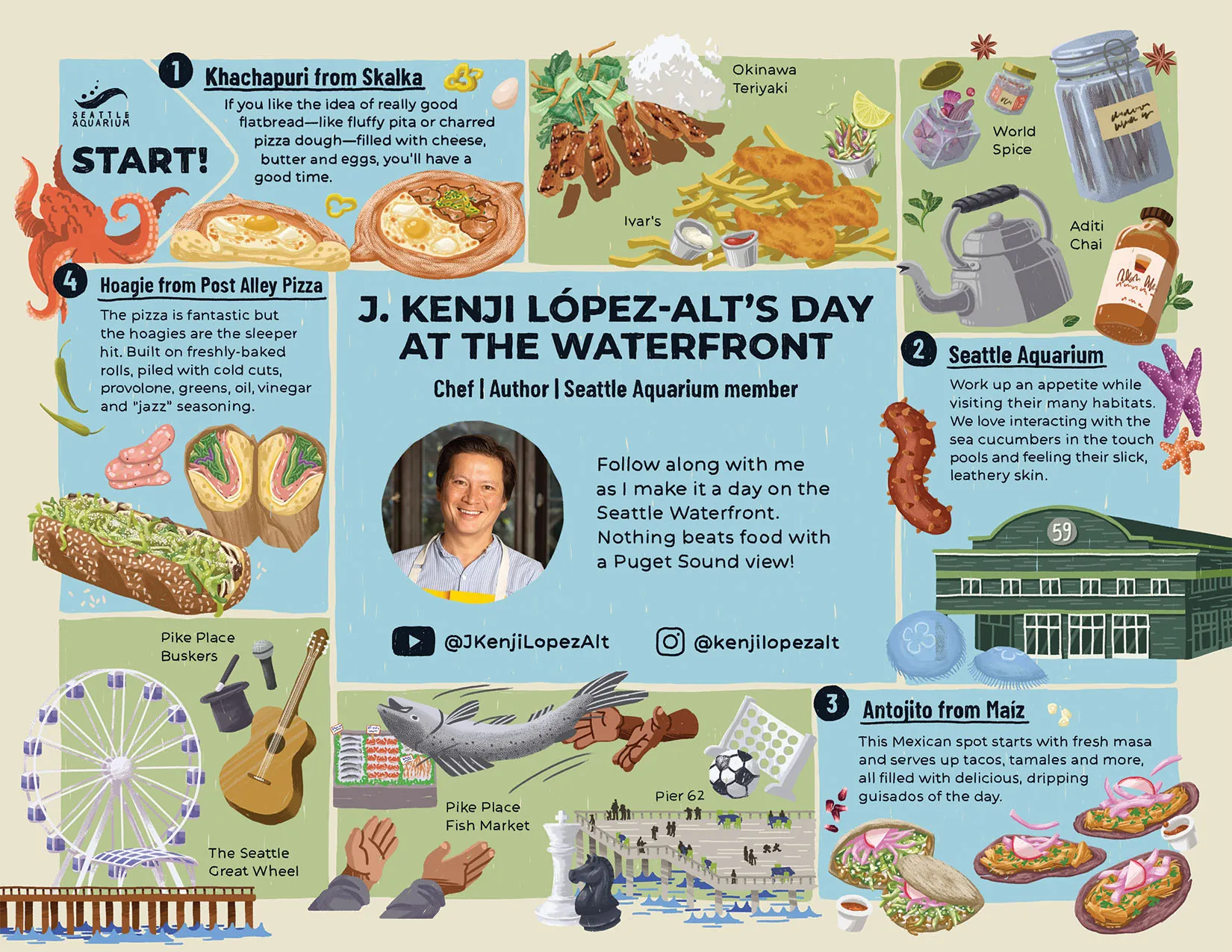

3, 2, 1…Ocean Pavilion!

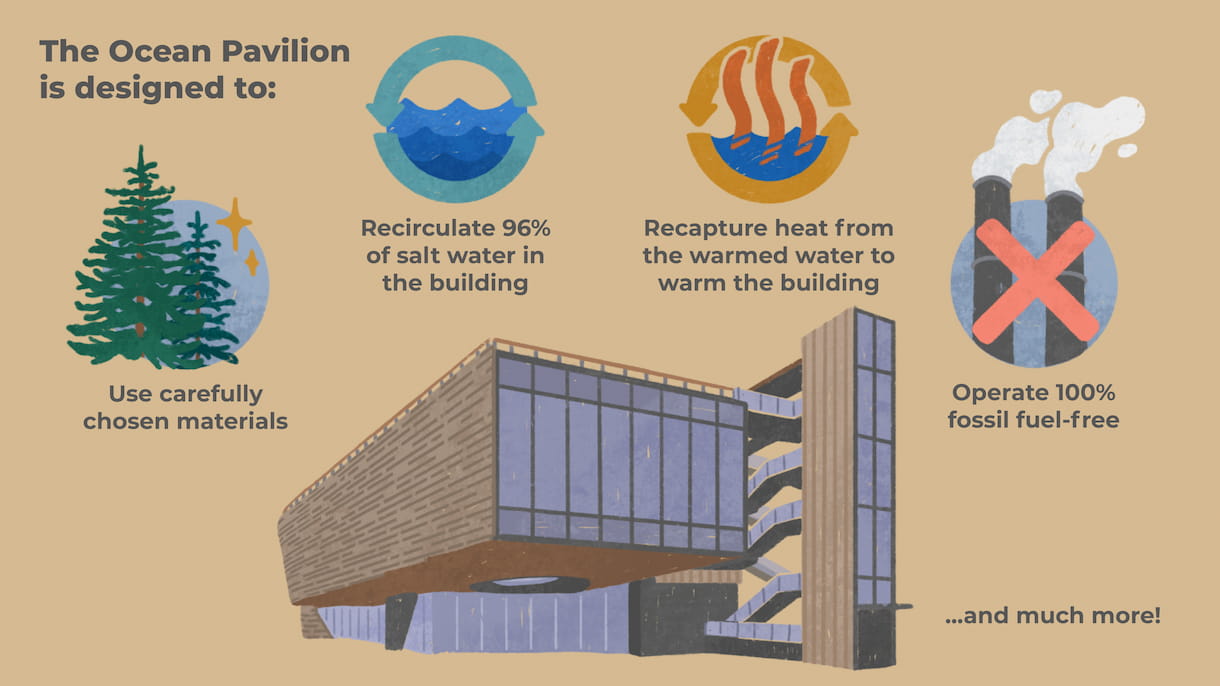

It’s the final countdown to opening the Seattle Aquarium’s Ocean Pavilion. This expansion of our campus and our mission has been over a decade in the making. Follow along as we prepare to open to the public on August 29!

- August 29, 2024

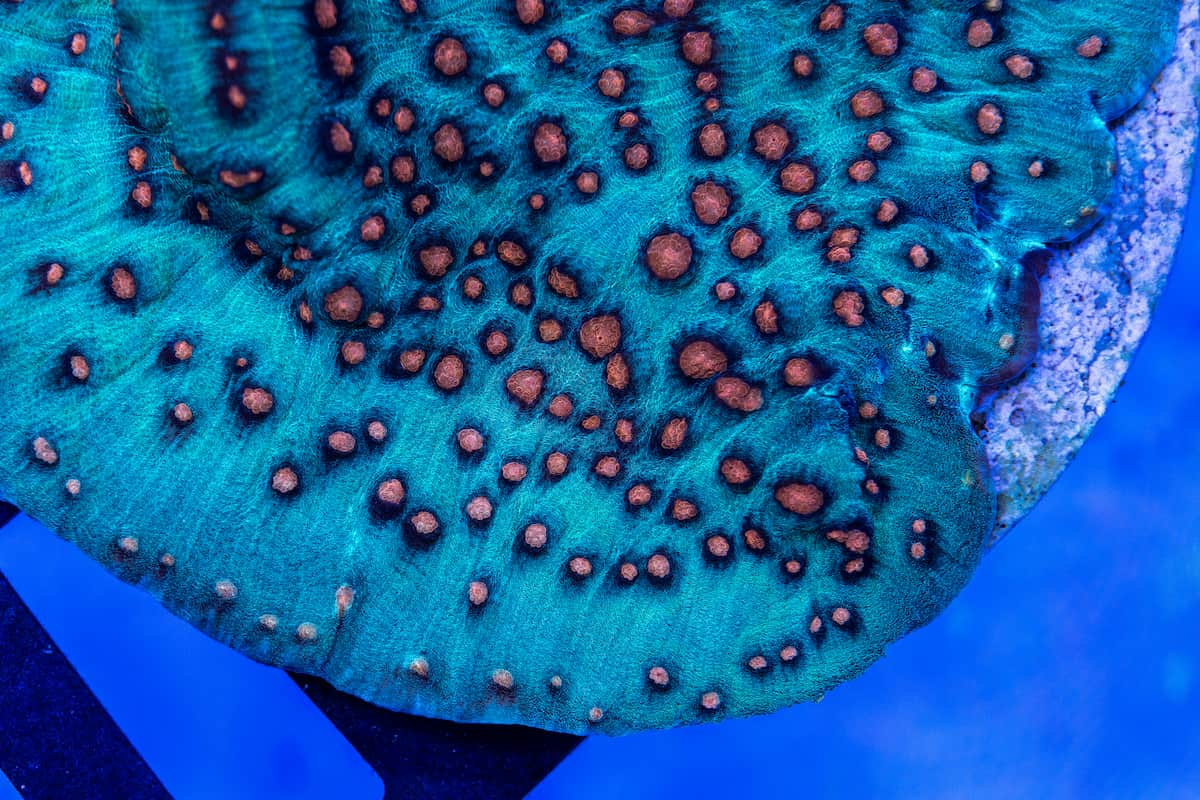

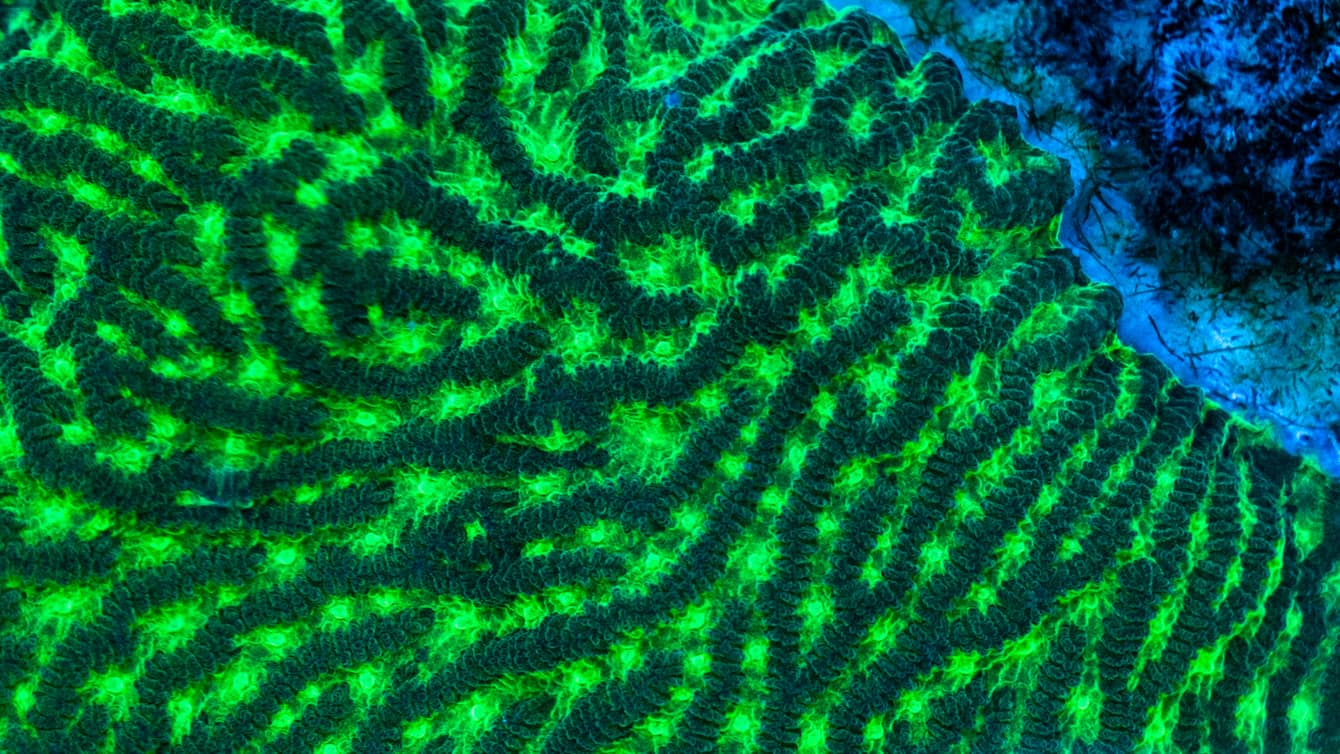

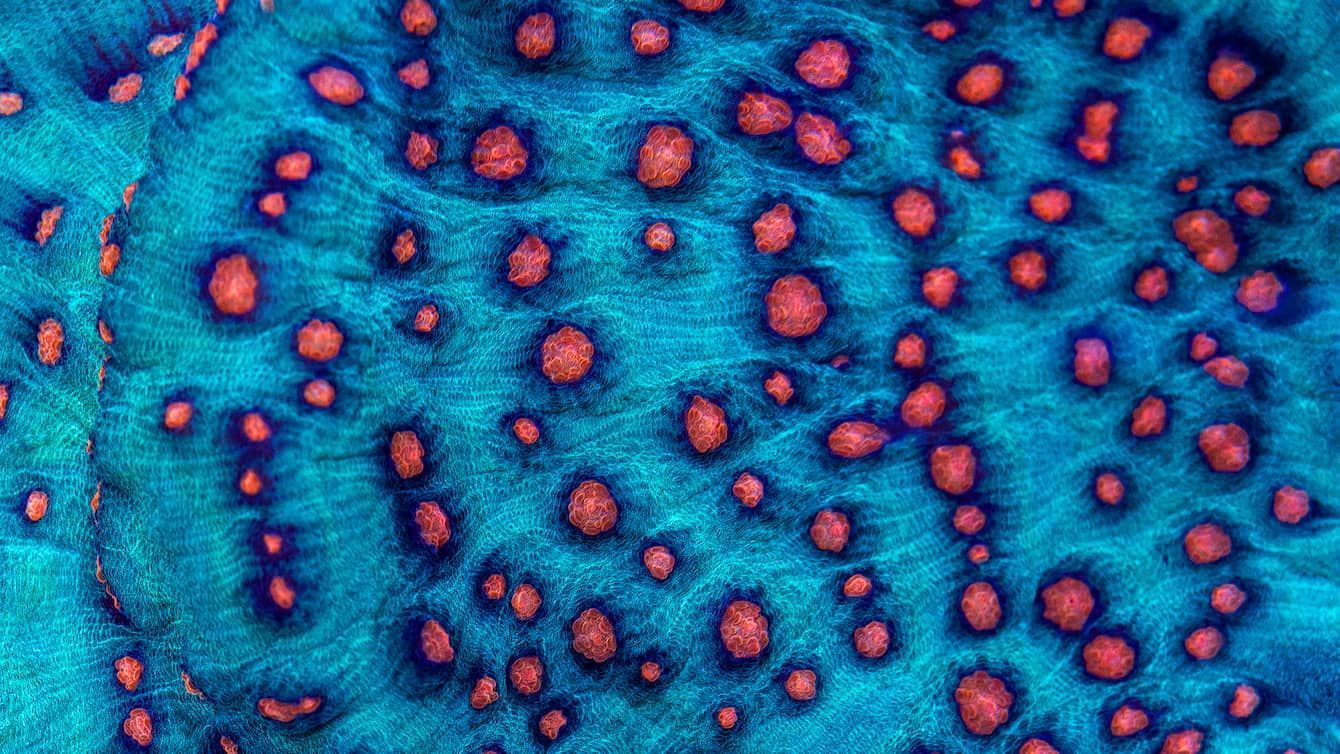

Wave hello to the open Ocean Pavilion!

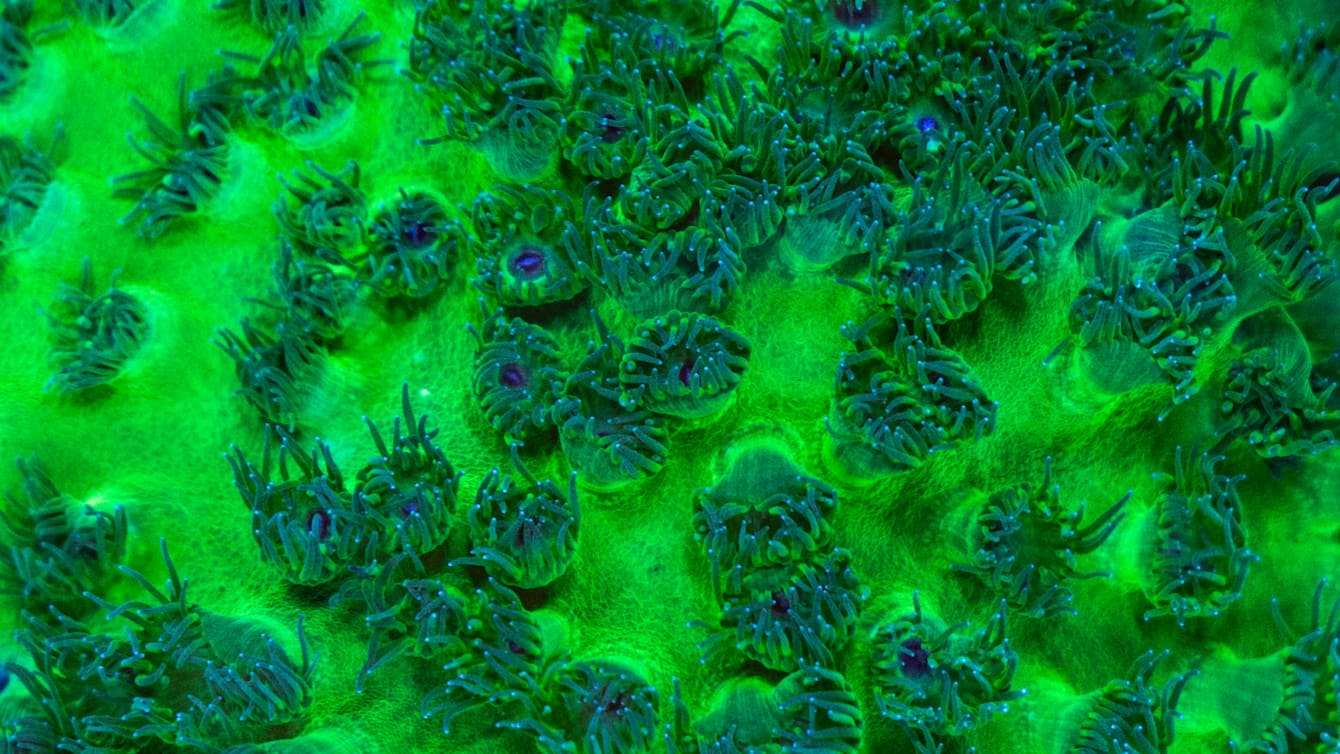

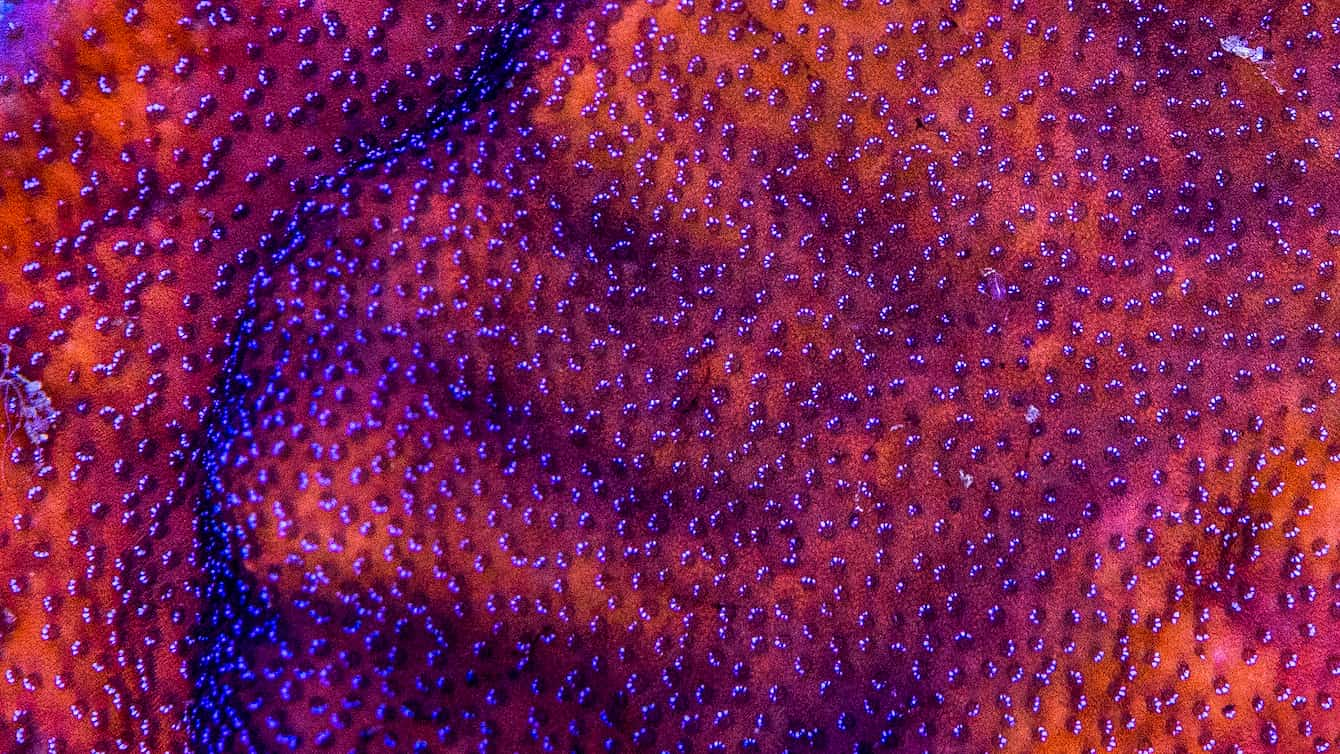

The day we’ve all been waiting for is finally here! Our Ocean Pavilion expansion welcomes its first public visitors today. We’re thrilled to share the vibrant underwater world of the Coral Triangle with guests. Plan a trip to see these immersive reef habitats for yourself.

- August 27, 2024

Wheel's in motion!

Visual artist Paige Pettibon (Confederated Salish and Kootenai) created this amazing seasonal round for the Ocean Pavilion. Depicting the cycle of life here, in the lands and waters of the Coast Salish people, it features beautiful illustrations of marine animals, phases of the moon, plants, people and more. Come give it a gentle spin when you visit!

- August 22, 2024

Speak of the devil

Meet the elusive devil scorpionfish, a new resident of our closer-look habitat, At Home in the Ocean. Scorpionfish are known for their venomous spines and the canny camouflage that helps them hunt. In the wild, their prey, including invertebrates and small fish, should keep an eye out for these ambush predators.

- August 19, 2024

You won't "belief" this playscape reef!

The Coral Reef Encounter at the Ocean Pavilion allows youngsters and families to explore what it might be like to live on a coral reef—discovering the sights, sounds and textures below the surface in a cozy, kid-size tunnel. You can even see what it’s like to be a clownfish, nestled within the tentacles of an anemone, in a colorful, cushioned nook! Learn more about the Ocean Pavilion’s habitats on our webpage.

- August 16, 2024

The tale behind this tail

Can you identify this species that recently moved into the Ocean Pavilion? Here’s a hint: He’s often spotted gliding through the building’s largest habitat, The Reef, with his tail trailing behind. Plan a trip to the Ocean Pavilion to see all of him for yourself!

- August 14, 2024

The view from her window

Not all Ocean Pavilion highlights are underwater. We’re also finishing “dryside exhibits,” as we call them, that tell stories about people inspiring hope and action for a healthy ocean. Can you guess which legendary marine scientist and ocean conservationist peered through this scuba mask decades ago? Hint: She famously said, “No water, no life. No blue, no green.”

- August 9, 2024

Who's new in The Reef

An Indo-Pacific leopard shark has glided into our largest habitat, The Reef. Once abundant in the Coral Triangle, these slow-swimming reef sharks are now nearly extinct due to overfishing and habitat loss. As a founding member of the international ReShark collective, we’re working with partners to restore their wild populations to marine protected areas.

- August 8, 2024

Going deep for healthy habitats

Our dive team is taking the Ocean Pavilion’s immersive experience to a whole new level. They’ve been cleaning The Reef habitat each day for weeks—even before any of the new animals had moved in—and will continue to do so after all the sharks, rays and schooling fish have settled in. Plan a visit to see the results of their hard work!

- August 7, 2024

Water you looking at? Fish in The Reef!

The first fish have entered The Reef, the largest habitat in our Ocean Pavilion expansion. These fish have been busy exploring their new space. We introduce animals, like this spotted sweetlips, to new habitats through a carefully-monitored method to ensure their safety. Learn more about that process (plus creating The Reef) in our recent web story.

Check back soon for more updates!