Sturgeon, tufted puffins and dwarf cuttlefish: They’re just like us!

Do you know someone who’s full of surprises—and just when you think you’ve got them figured out, they do something entirely unexpected? Our summer SEAlebrities are like that, too! They’re not always what they seem to be, so look closely. Some change colors, others are showy birds that swim like fish. Check them out on your next visit to the Seattle Aquarium!

White sturgeon: fish with an identity crisis?

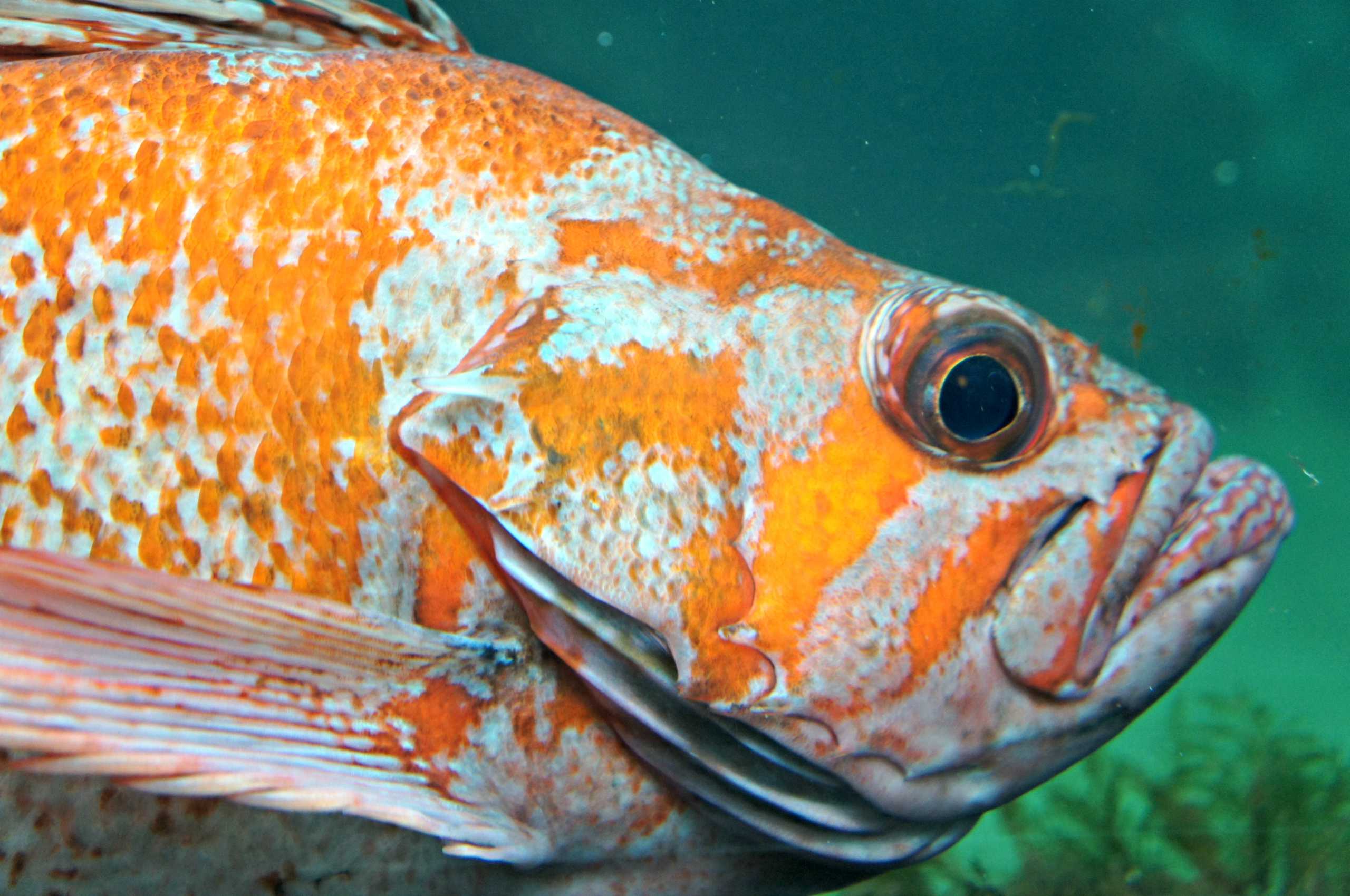

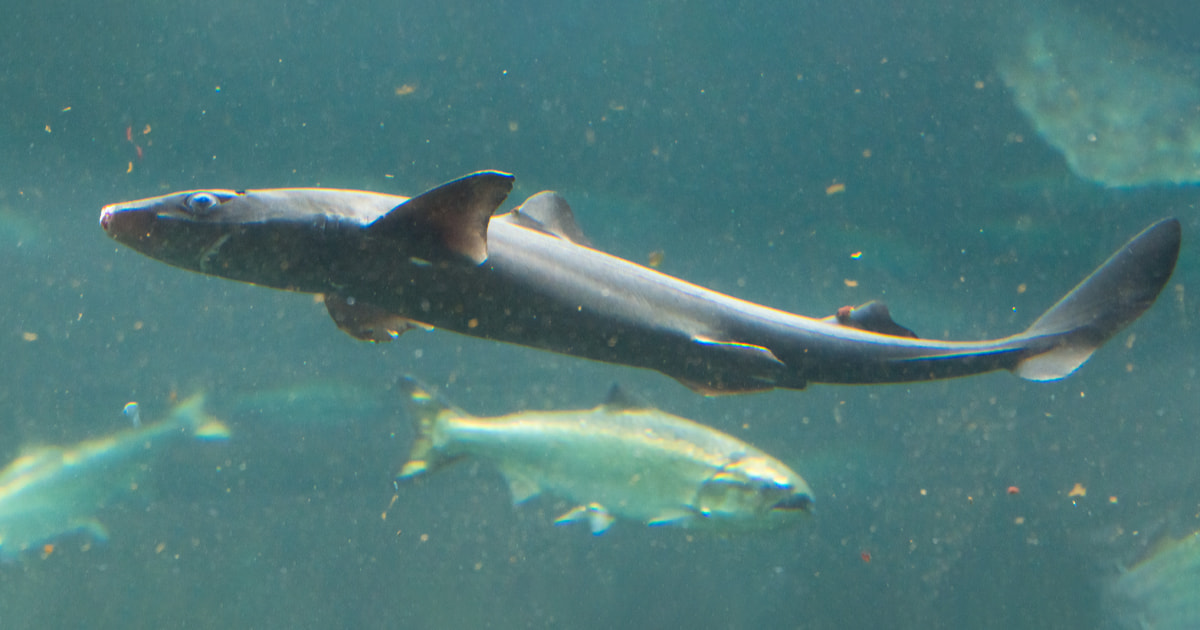

One glance at their long bodies, pointy snouts and dorsal fins and you might ask, “Who let the sharks in?” Often mistaken for sharks, white sturgeon, Acipenser transmontanus, are bottom-dwelling fish that live in the temperate waters of the Pacific Coast from Alaska to upper Baja California.

HOW ARE STURGEON JUST LIKE US?

They have what it takes to protect themselves.

Like sharks, sturgeon have been around since the time of the dinosaurs. They have smooth skin and a skeleton made of cartilaginous scutes, not bone. Reminiscent of scales, the rows of scutes protect the sturgeon’s vital internal organs. Unlike sharks (or us), sturgeon have no teeth. Smile!

They like to lay low and feel things out.

Sturgeon hover over sandy floors of the ocean and estuaries to forage for food with their barbels—long, whisker-like feelers above their mouths. They drag their barbels along the bottom, searching for shellfish, invertebrates (animals with no backbone) and small fish, then suck their prey into their mouths and swallow it whole.

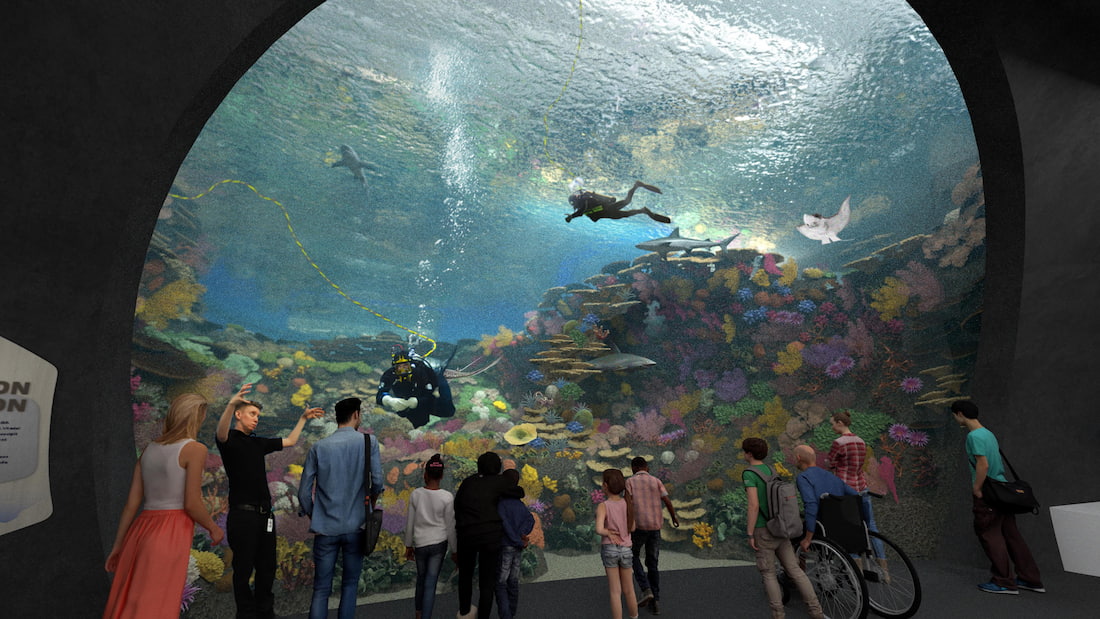

Can you spot a sturgeon? Test your observation skills at our Underwater Dome habitat.

Tufted puffins: parrots of the sea

Tufted puffins, Fratercula cirrhata, spend summers in remote island colonies and winters on the open sea. These diving birds (alcids) seem to fly through water as easily as air. Yet their webbed feet are also used to burrow into cliffs or slopes where they will build nests safely hidden from predators and food-snatching gulls.

HOW ARE TUFTED PUFFINS JUST LIKE US?

They dress for the season.

In summer, tufted puffins shed their dull winter feathers and bill coverings for a more colorful look. Legs and feet turn bright orange. An ornamental bill plate appears. Golden tufts accent a white “face mask.” That’s how they gain a mate—and the nickname “parrots of the sea.”

They search for love that lasts a lifetime.

Once they’re dressed to impress, courtship begins. Tufted puffins rub bills, strut and “skypoint” (pose with bills thrust upward, wings and tail raised). Couples then find a suitable spot for a home, dig a burrow, build a nest and take turns incubating their single egg. Bonded couples often form lifetime partnerships and return to the same area each year.

What are the tufted puffins wearing today? Check them out in our Birds & Shores habitat. (Phelps will be sporting an orange band on his right leg.)

Dwarf cuttlefish: now you see them, now you don't

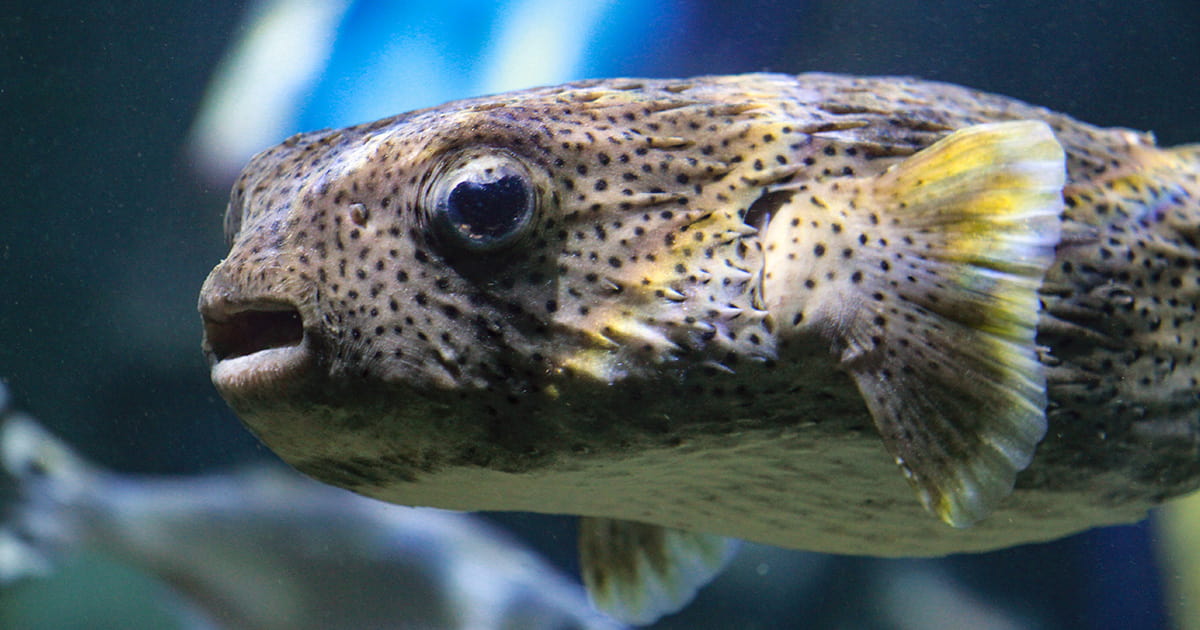

Dwarf cuttlefish, Sepia bandensis, are native to coral reefs of the Indo-Pacific region. Cousins to squids, octopuses and nautiluses, these tiny cephalopods have keen brains, three hearts and excellent vision that’s essential for hunting. They are often called “chameleons of the sea” for their skill at quick-change camouflage.

HOW ARE DWARF CUTTLEFISH JUST LIKE US?

They know when to fade into the background—and when it’s time to be seen.

Their small size makes dwarf cuttlefish easy prey, but their ability to quickly change color, skin texture and pattern makes them harder to spot. Conversely, a hungry cuttlefish disguised as a rock will find it much easier to sneak up on their next meal. And sometimes, male cuttlefish display female colors to get past bigger, stronger suitors.

They like to go out for a stroll.

Dwarf cuttlefish have eight arms encircling their mouth. They often appear to “walk” along the ocean floor using two of their eight arms. When a tasty morsel appears, their arms open quickly and two feeding tentacles shoot out, grabbing the prey and pulling it toward the cuttlefish’s beak and mouth.

See Cuttle Puddle and the other dwarf cuttlefish in action in our Pacific Coral Reef habitat!

Just like us, all of our SEAlebrities need healthy habitats to thrive. The threats to their homes are largely manmade. Find out what you can do to preserve the marine environment they—and we—depend on. Visit our Act for the Ocean page to learn more.