“Like human nurses—but in the veterinary field:” All about vet techs at the Seattle Aquarium

This story is part of our series, The Doctor Is In—highlighting our veterinary team’s expertise in service of animal wellbeing.

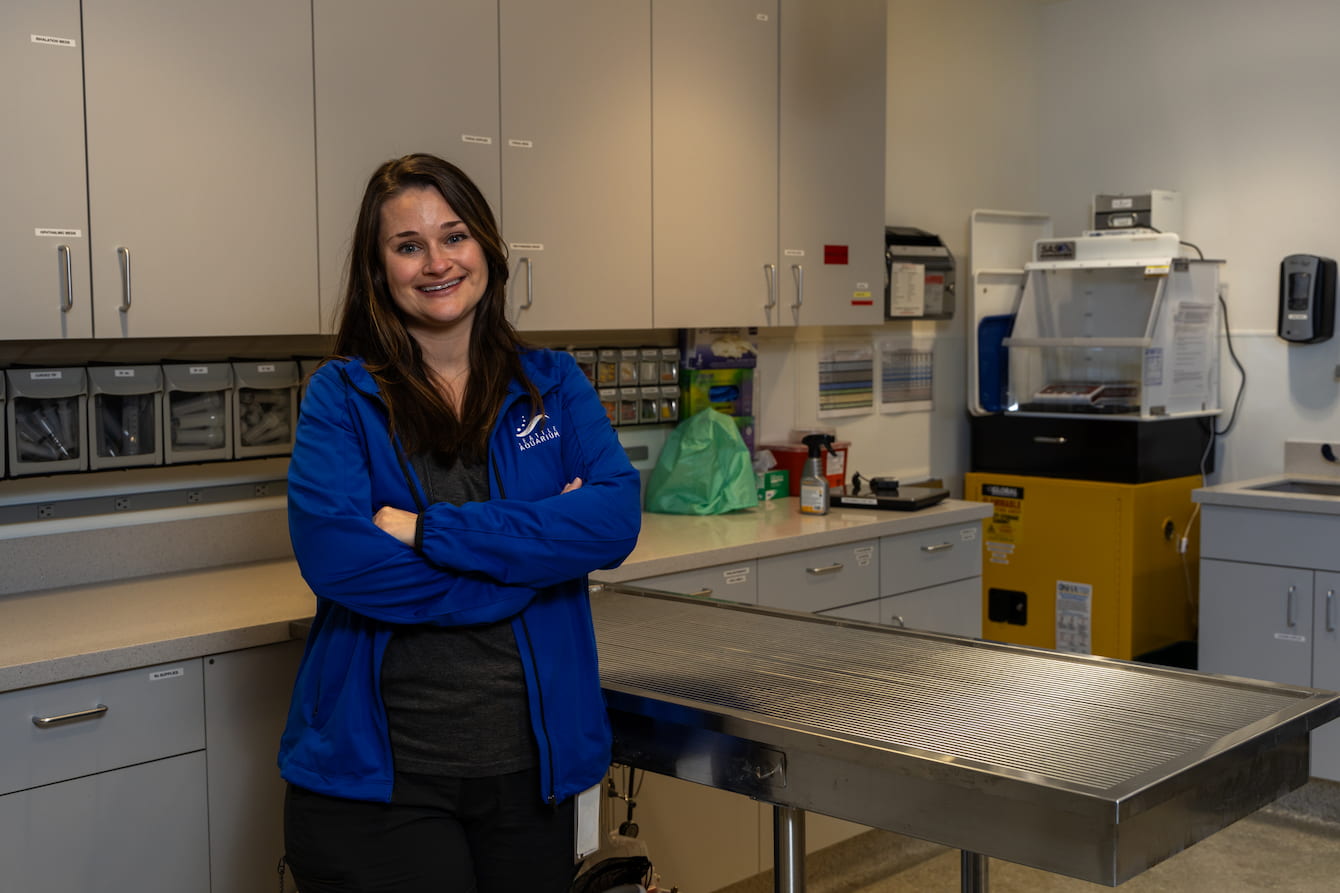

Veterinary technicians—or vet techs—are an integral part of the veterinary care team here at the Seattle Aquarium. But what does it mean to be a vet tech, and what kinds of education and experience are needed to work as a vet tech in an aquarium setting? Lindy McMorran, BS LVT Cert AqVN /T, and Erika Russ Paz, BS LVT, recently sat down with us to share some details.

First things first: What's a veterinary technician?

“It’s like a human nurse—but in the veterinary field,” explains Lindy. Similar to a nurse in a clinic or hospital, Lindy and Erika might spend a typical day at the Aquarium running anesthesia during a procedure, dispensing medications, taking x-rays, maintaining supplies and equipment for the Aquarium’s Veterinary Care Center and scheduling exams. They may also be found working with animal care staff to train behaviors that help with animal care, such as the ability to give an injection or take a blood sample with an animal’s cooperation.

Both women have Bachelor of Science (BS) degrees—Lindy’s in marine biology; Erika’s in marine science with a minor in biology—and licensed veterinary technician (LVT) credentials. Earning the credential requires about two years of full-time studies, followed by a national exam and state test. (Details, including alternative criteria, can be found on the Washington State Department of Health website.)

Most vet techs go on to work at the kind of veterinary clinic where you might take a pet dog or cat, so the curriculum focuses on their care. Although much of the core training applies to animals of all kinds, “there was no training that was specific to aquatic animals,” notes Lindy.

For vet techs in aquarium settings, that’s where hands-on experience, internships and/or additional courses—not to mention a passion for the marine environment—come in.

Says Erika, describing highlights of the path that brought to her to the Aquarium, “I worked as an educator and marine science camp counselor at an aquarium during college. I also interned at an aquarium and as a wildlife rehabilitator. And, after graduation, I spent time as an observer in Alaska, collecting data to help manage our fisheries. I worked with PAWS, caring for a wide variety of species from the Pacific Northwest, as well. ”

That’s in addition to seven years in a general veterinary practice before joining our team early this year. “A background in marine science and biology, along with a passion for the ocean and care of animals, ultimately led me to the Aquarium,” Erika comments.

Specialties: Not just for human nurses

“Human nurses can have specialties, like oncology or pediatrics. Veterinarians can have those same kinds of specialties,” Lindy says. “But for vet techs, specialties are less common.”

Like Erika, Lindy augmented her schooling by working with marine animals—for example, as a volunteer for SR3, a local organization focused on marine mammal rescue and rehabilitation, and here at the Seattle Aquarium. She’s been focused on aquatic animals since 2007: as an intern, a lab assistant, an instructor and more.

Through her years of specific experience with aquatic animals, Lindy recently earned a new credential, Certified Aquatic Veterinary Technician, from the World Aquarium Veterinary Medical Association (WAVMA). She’s just the second person in the continental United States to achieve the certification, which became available from WAVMA at the beginning of 2023, joining select others from around the world.

Put simply, the new credential recognizes Lindy’s expertise with marine animals. “It’s one of the only ways a vet tech in the aquarium field can prove their experience,” she notes. “For instance, there is no board certification specialty for vet techs in aquatic medicine, but there is one for zoos.”

Broad experience + passion = a well-rounded, expert team

“Growing our veterinary team and seeking people with diverse backgrounds and areas of expertise helps ensure that each animal receives the individual care they need, which benefits their wellbeing,” comments Lindy.

That adaptability, always important, is even more so as the Aquarium expands with the opening of the new Ocean Pavilion this summer. Interested in learning more about veterinary care at the Seattle Aquarium? Check out our web story devoted to the full team.