Get to know some of the Aquarium’s cutest “couples”

Valentine’s Day is just around the corner, making this the perfect time to introduce you to a few of the species in our care that form bonded—sometimes even lifelong!—pairs.

But before you get too starry-eyed…not surprisingly, relationships in the animal kingdom are quite different from human relationships. Animals may pair up for a moment, a season or a lifetime. Even when they mate for life, it’s not as romantic as it sounds.

Animals that choose to mate year after year do so for practical reasons: they’re busy establishing territory, incubating eggs and/or caring for young. Spending time and energy attracting a new mate every year would minimize reproductive time—so, in a sense, animals that form lifetime partnerships are just being practical.

That said, isn’t it fun to celebrate romance (even if it doesn’t follow the strictest definition of the word?). Please join us in saluting some species at the Aquarium that form twosomes—and be sure to blow them a kiss during your next visit!

Birds of a feather bonding together: tufted puffins

Tufted puffins tend to be monogamous and often form lifetime partnerships after they begin breeding at approximately three years of age. The parents-to-be return to the same burrow each year and prepare their home for the arrival of a chick. Females usually lay just one egg, which both parents take turns incubating until the chick hatches about six weeks later. Here at the Aquarium, over the years, we’ve witnessed the same shared incubation and feeding behaviors with the tufted puffins in our care.

“Billing” is the term for a courtship behavior commonly seen during the breeding season, in which puffins exchange taps on one another’s bills.

Fast fact: During the summer breeding season, tufted puffins display an ornamental bill plate, as well as brilliant orange legs, a white “face mask” and distinctive golden tufts above the eyes. In the winter, the color of their legs becomes dull, their brilliant white “mask” is replaced with dark feathers, their tufts disappear and their bill plate falls off.

Plenty of (yelloweye rock)fish in the sea

They may not be seen together year-round, but two large yelloweye rockfish in the Window on Washington Waters habitat often form a cozy twosome during winter and early spring. When that happens, they’re frequently seen swimming circles around each other (during which time the male turns very dark in color) in a fishy courtship dance.

Is this a look of love from a yelloweye rockfish? Only the intended mate knows for sure!

Fast fact: Rockfish have very long life spans compared to many of the world’s fish species—individuals of some rockfish species can live for 100 years or more! Those life spans mean that many don’t begin breeding until they’re about 20 years old. When they do breed, they don’t lay eggs like most fish species: instead, they give birth to live young.

Not a lone wolf (eel)

Wolf eels may mate for life or change partners from year to year. Regardless, both male and female care for eggs as they develop. The female lays her eggs—up to 10,000 of them!—in a den, then both parents guard them for the 13–16 weeks it takes for them to mature and hatch. The parents-to-be may even wrap their bodies around the egg mass to keep it safe from predators. During this period, only one parent at a time goes out to feed.

The Window on Washington Waters habitat here at the Aquarium is home to three wolf eels: two males and a female. If you’re lucky, you may see two of them hanging out together in a den!

Fast fact: Unlike the moray eels in our care in The Reef habitat at our new Ocean Pavilion, wolf eels aren’t true eels. They’re actually just long, skinny fish! But, like moray eels, adult wolf eels prefer enclosed spaces. Once they choose a den, they back their bodies into it, then stick their heads out to watch for prey.

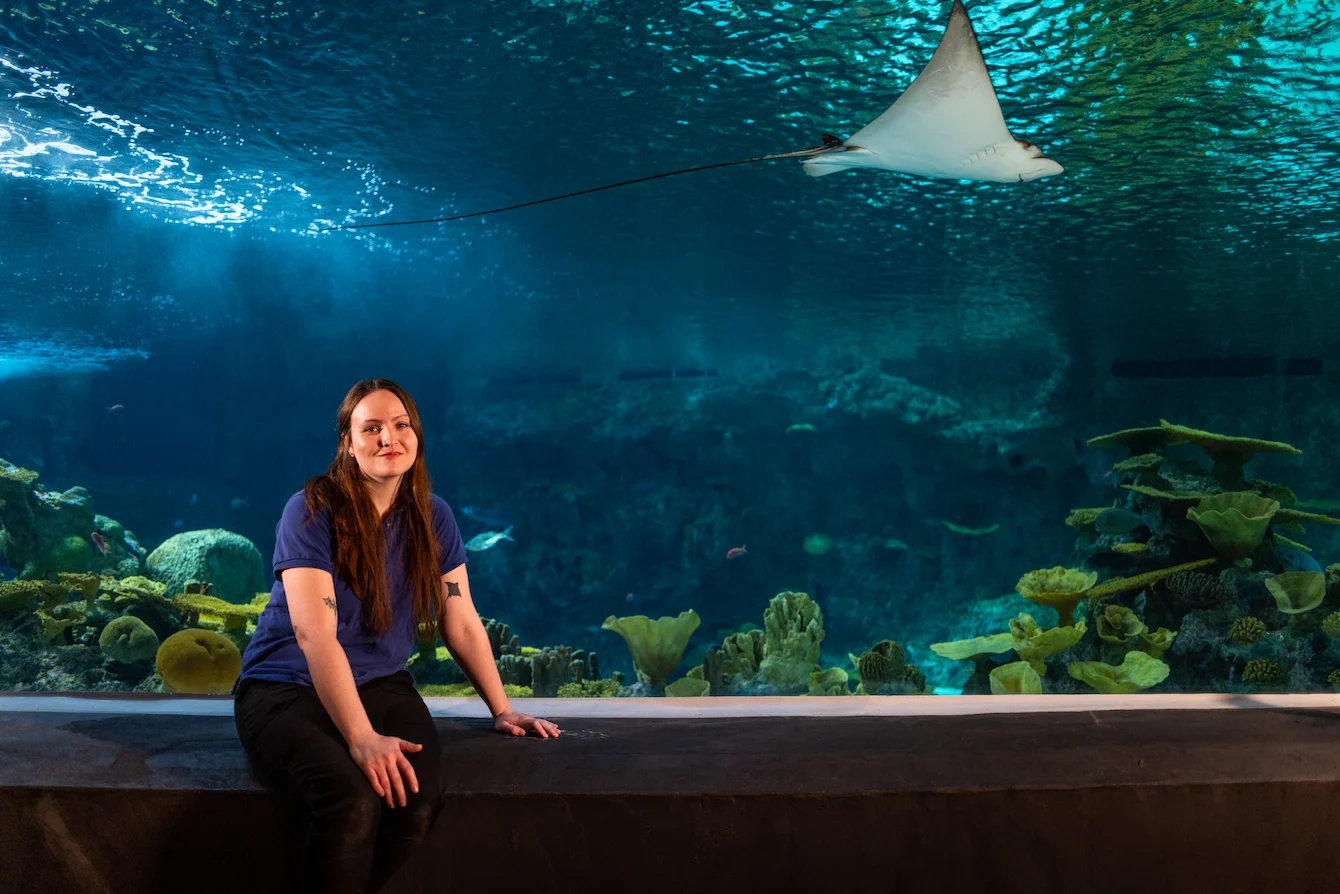

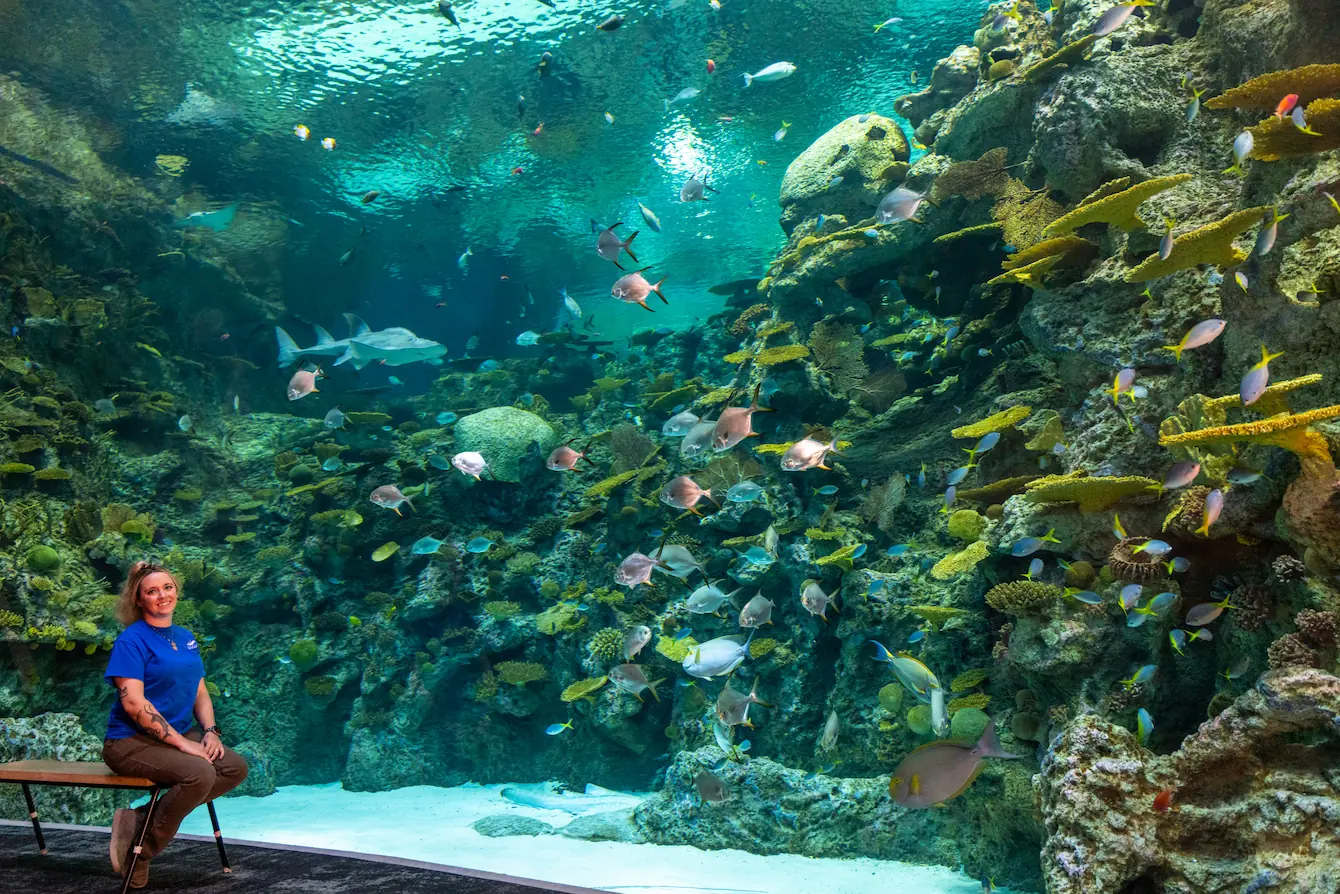

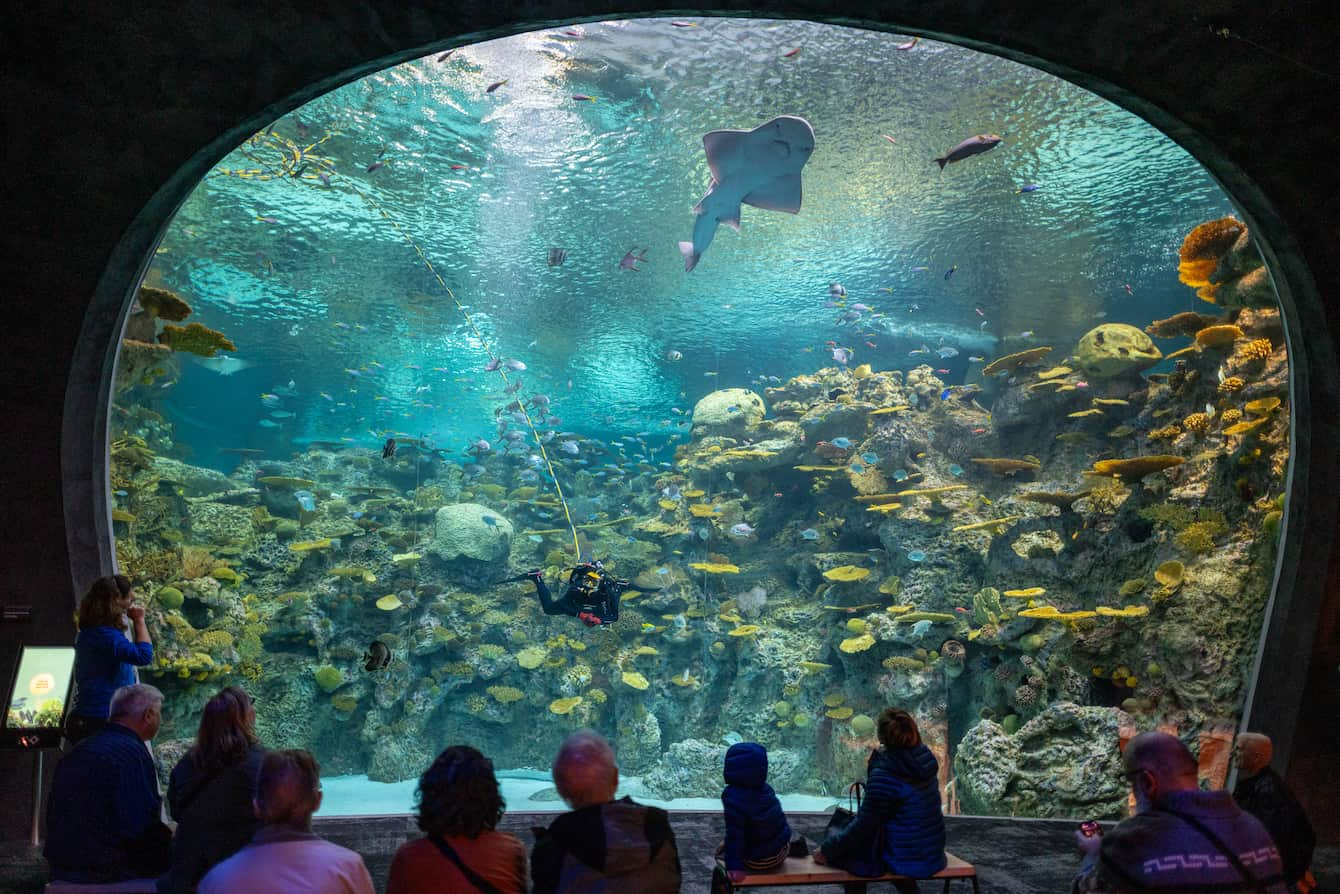

Check out our website to learn more about tufted puffins, rockfish and wolf eels. Even better, come see them in person at the Seattle Aquarium! And don’t miss the warm and bright Ocean Pavilion—a virtual trip to the tropics is the perfect antidote to a chilly, wet day here in the Pacific Northwest. Plan a visit today!