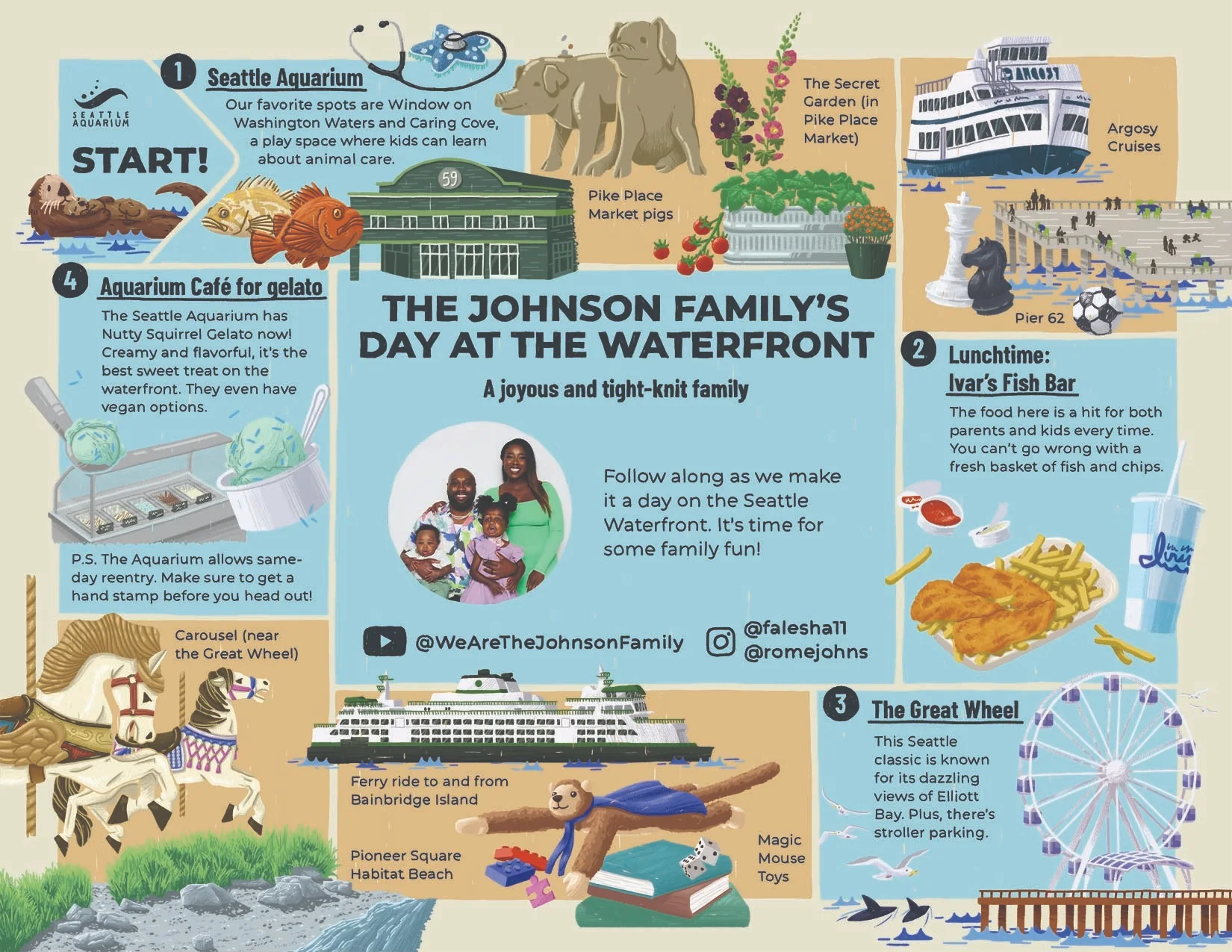

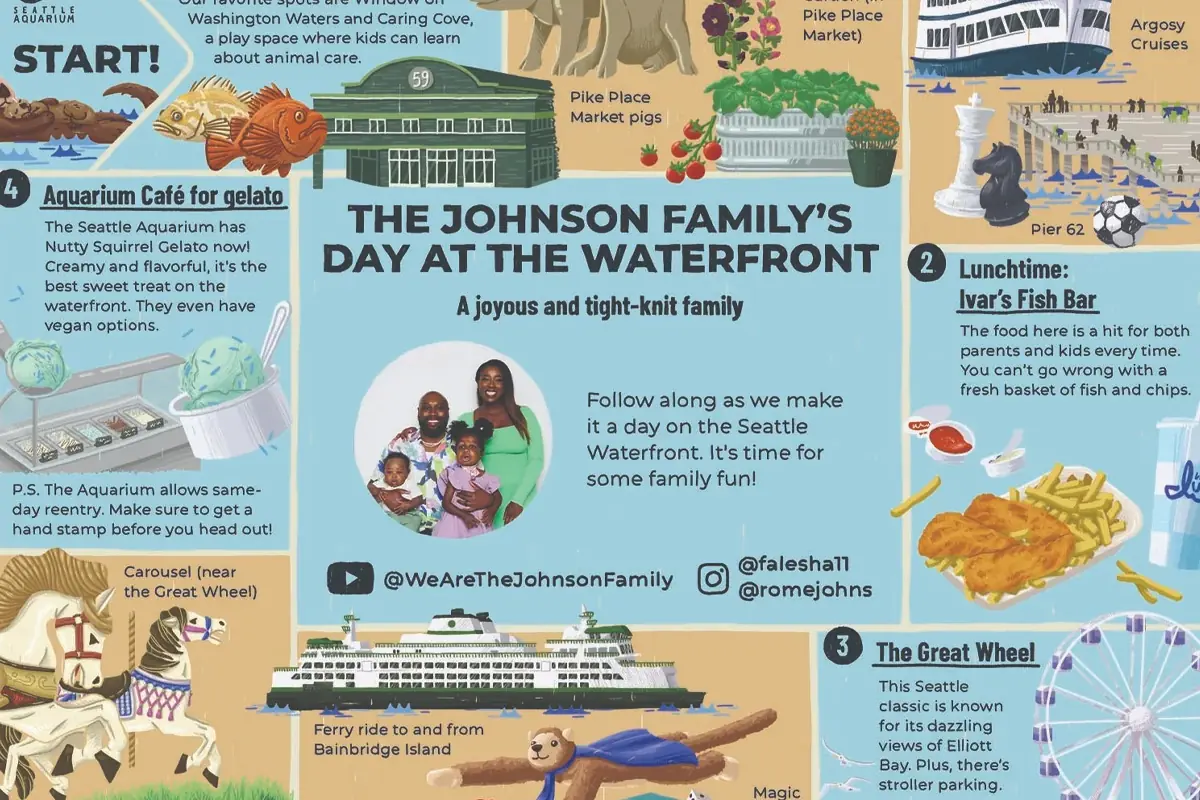

How the Johnson family makes it a day at the waterfront

The Seattle Aquarium teamed up with Rome and Falesha Johnson—parents to Caliyah Joy and Romen—for a day of family fun on the Seattle waterfront. Dive in to see their adventures!

Click the image below to see the full-size itinerary.

The Johnson family’s day at the waterfront

Follow along as we make it a day on the Seattle Waterfront. It’s time for some family fun!

1: Seattle Aquarium

Our favorite spots are Window on Washington Waters and Caring Cove, a play space where kids can learn about animal care.

2: Lunchtime: Ivar’s Fish Bar

The food here is a hit for both parents and kids every time. You can’t go wrong with a fresh basket of fish and chips.

This Seattle classic is known for its dazzling views of Elliott Bay. Plus, there’s stroller parking.

4: Aquarium café for gelato

The Seattle Aquarium has Nutty Squirrel Gelato now! Creamy and flavorful, it’s the best sweet treat on the waterfront. They even have vegan options. P.S. The Aquarium allows same-day reentry. Make sure to get a hand stamp before you head out!

More Seattle waterfront itinerary highlights

- Pike Place Market pigs

- The Secret Garden (in Pike Place Market)

- Argosy Cruises

- Pier 62

- Magic Mouse Toys

- Pioneer Square Habitat Beach

- Ferry ride to and from Bainbridge Island

- Carousel (near the Great Wheel)