This site uses cookies. View our Cookie Policy to learn more about how and why.

This site uses cookies. View our Cookie Policy to learn more about how and why.

When people hear that Aina Hori grew up in Hawai‘i, invariably they assume she surfs. She chuckles at this fantasy, clarifying that yes, the beach was her playground, and no, she didn’t ride the waves. Nonetheless, she loved the ocean, and her appreciation grew on elementary school outings. “In Hawai‘i, a lot of field trips take you to nearby beaches,” recalls Aina. “They build an understanding of where we live and why we have to take care of our environment.”

It was on these excursions, as she interacted with volunteers, that Aina discovered she wanted to be connected to the sea. Her interest developed as she spent hours exploring tide pools and getting familiar with the ocean. Eventually, when she set off for the University of Washington (UW), unsure of her major, she heeded the wisdom of her parents, who advised her to study something she really enjoyed. Luckily, the UW had just established a new marine biology major, and in June 2022, Aina was among 50 students in the first in-person graduating class. This fall, she’s continuing her studies through the School of Marine and Environmental Affairs at the UW.

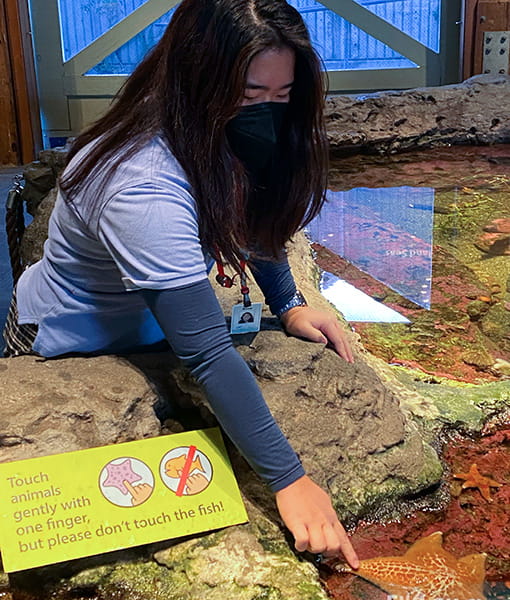

Aina heard about volunteering for the Seattle Aquarium from her classmates and decided she’d like applying her schooling to the real world. On her Saturday shifts as a habitat interpreter, she meets many families with children. Remembering how her experience with volunteers impressed her as a kid, she encourages those who are interested, letting them know a career in marine biology is possible.

What does she like most about her role? “It’s a pleasure to show visitors who’ve never experienced the Pacific Northwest ecosystem—let alone water because they’re from landlocked areas—that you can get an urchin hug…it has a mouth…it’s an animal…the amount of times that a person’s face ‘glows up’ never gets old!” she says delightedly.

Between graduate school and volunteering, Aina’s calendar is full. But she still makes volunteering at the Aquarium a priority, as she feels that in addition to increasing her aquatic knowledge, it also enhances her life skills, such as interpersonal communication and being at ease with people from all around the world. And she’s built a network of co-workers and supporters who she can rely on, wherever her future takes her.

Aware that balancing school and other responsibilities is challenging, she offers this advice for students contemplating volunteering: “Given the Aquarium’s requirements, if you want to help and are limited on time, let them know you’re interested along with your availability and they’ll work with you to find appropriate opportunities.” There are many prospects, including interpretation at evening events and seasonal needs like the Beach Naturalist and Cedar River Salmon Journey programs—positions that might not conflict with classes and other life obligations.

Aina’s commitment to the Aquarium is clear: she’s given more than 230 hours of service in her three years as a volunteer. One of the key reasons she loves being a habitat interpreter is that she helps visitors realize that each individual can make a difference to our environment. “I keep volunteering because, by sharing, I create a fascination so people care and want to help change the world for the better,” she says.

Ready to join Aina in sharing the Seattle Aquarium’s mission of Inspiring Conservation of Our Marine Environment? Register for our upcoming volunteer orientation today! You’ll find all the details on our volunteer webpage.

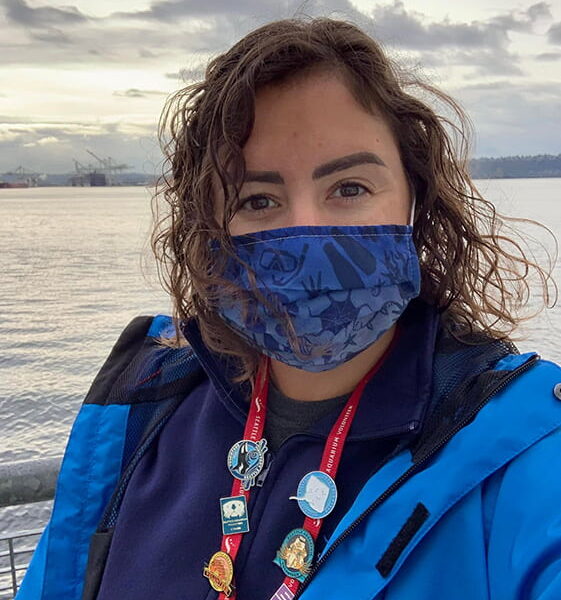

Whitney Golay started volunteering for the Aquarium in 2012 as a beach naturalist. In 2014, she added diving to the mix and, at last count, had logged more than 550 hours of service—all of them in our Pacific Coral Reef habitat. “It’s essentially a mini vacation where I can see tropical fish up close without having to go to Hawai‘i,” she says, “And I’m giving back at the same time.”

But Whitney’s appreciation for the marine environment isn’t limited to tropical waters. She studied marine biology at the University of Washington because of her love of the Salish Sea—a love she shares with her dad. “When I was growing up, my family would spend weekends on the Kitsap Peninsula, checking out all the tide pools and some of my favorite Salish Sea creatures, nudibranchs,” she says.

Whitney’s journey to becoming a diver started in 2010, while she was working in Friday Harbor, analyzing underwater rock wall photos on a computer. When a co-worker signed up for a scuba class, she decided to join. “And, a few months later, I was getting to look at all the underwater sights that I’d been staring at through the computer screen,” she comments. She got her dive masters in 2014 and started volunteering for us the same year.

Now, Whitney spends her volunteer shifts diving in the warm-water habitats at the Aquarium, where she feeds the fish, watches the antics of the porcupinefish (one for her favorites), cleans the habitat and waves to guests on the “dry side.” She especially loves waving to young girls, who she hopes are inspired to share her passion for the ocean and conservation.

When asked what she would say to someone who is considering becoming a volunteer diver at the Aquarium, her short answer is, “Do it!” She adds, “It’s a unique opportunity. You’re able to see some of the species up close that you are never going to see otherwise.”

Potential volunteer divers are required to have a minimum of 12 dives in local diving conditions within the last year and an advanced open water diver certificate. Divers must also commit to at least one three-hour shift at the Aquarium, every other week for at least a year. Interested in learning more? Visit the adult volunteer page on our website and fill out our diver experience form!

Introducing Crush the western snowy plover, one of our new Seattle Aquarium SEAlebrities! After being injured, she was rehabilitated at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California, then moved to make her home with us in 2019. You can find her in our Birds & Shores habitat.

At first glance, you might think that people don’t have a lot in common with Crush and her species, Charadrius nivosus. After all, humans can’t fly (at least, not unassisted) and human adults are pretty much guaranteed to weigh more than two slices of sandwich bread (or about 2 ounces, which is where adults of this species typically tip the scales). As it turns out, though, we share a lot of common ground!

During their breeding season, May to September, both males and females add a little extra flair: black stripes above their eyes, near their ears and along their necks (although these markings are less distinct on females).

The bodies of western snowy plovers are pale, sandy brown on top with a white underside. What else is pale, sandy brown? Sand, of course! And sandy beaches are where western snowy plovers make their homes, along the Pacific coast from Washington to northwest Mexico. Unless they’re in motion, their coloration and tiny size make them hard to spot in the wild.

Western snowy plover eggs hatch after an incubation period of 26–33 days. And then the chicks are literally off and running: They’re able to leave the nest and forage on their own within three hours! What are they looking for? Prey like insects, marine worms, crustaceans and invertebrates.

While their eggs are incubating, both male and female western snowy plovers may defend their nest and the surrounding area by posturing (or spreading out their wings), chasing and even fighting potential predators (such as gulls and falcons) or other perceived threats to their families-in-the-making.

Western snowy plovers make their nests on the sandy beach, in slight depressions on the dry ground (sometimes even in human footprints!). And they line those nests with just about anything they can scavenge: pebbles, shell fragments, fish bones, bits of driftwood and more.

Western snowy plovers have been listed under the Endangered Species Act since 1993, and their numbers are still declining. Unfortunately, human impacts are the main problem for this struggling-to-survive species. The good news is that we can be part of the solution too! Read our western snowy plover webpage for more details and to learn how you can help.

Sharks and rays are vanishing at an alarming rate due to fishing and habitat loss. When these keystone species disappear, their entire ecosystems collapse. For over two years, the Seattle Aquarium has been part of a global coalition devoted to changing the story and “resharking” the ocean.

In August 2022, the coalition—called ReShark—achieved a major milestone in its first project. Eggs laid by Indo-Pacific leopard sharks (Stegostoma tigrinum) in the SEA LiFE Sydney Aquarium were moved from Australia to a new shark nursery in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. Pups have already hatched and are growing quickly! When they’re mature, they’ll be released into their home waters to help bring back their species locally and safely within marine protected areas. And ReShark’s work will continue, with new eggs, new locations and new species to recover.

Dr. Erin Meyer, Director of Conservation Programs & Partnerships at the Seattle Aquarium, has helped build the coalition from its earliest days and chairs the project’s Steering Committee. She shared five key lessons from the first chapter of its work.

The first time I heard the idea for what would become ReShark was in early 2018, about a month after I got the job at the Aquarium. I then became part of a small group of colleagues from around the world that kept talking about the possibility over the next two years. Could we do it? If we did, how would it work? We formally launched the first project in February 2020. Then the pandemic began. Still, we kept going, working virtually with local leaders in Indonesia to get permits, building a nursery for baby sharks at the Raja Ampat Research & Conservation Centre, training aquarists in Indonesia, finding viable eggs to ship. Moving our first set of eggs in August took a huge amount of work behind the scenes by so many people. (See all ReShark partners involved in this work.) In August, I got to see the nursery for the first time in person—this amazing structure we’d all been working toward for two years. For me, that’s when it became very real.

70+ partners | 13 countries | 2.5 years of planning

Conservation is about people. And we are agents of change, both damaging and regenerative. Collaborative conservation is intentional, co-led and begins with a blank slate. ReShark’s first project is co-designed and co-implemented with the West Papuan government in Indonesia as critical partners in this coalition. It would not have been possible without local leadership. Doing cross-cultural conservation work in a way that centers the priorities and needs of the people in the country where the work is taking place is incredibly important for this project and for the future of conservation in general. I often hear in the environmental justice community that work like this moves “at the speed of trust.” It takes years to earn trust and seconds to break it. As ReShark grows to include more species and more locations, we will continue to center the perspectives and expertise of local partners, breaking the colonialist approach to conservation, challenging our biases and checking our privilege. Conservation requires leaning into uncomfortable spaces, and we’re not shying away from that.

I’m not a shark biologist; my expertise is in invertebrates, ecosystems and conservation action. I’ve learned that it’s a far harder thing to move eggs around than I ever thought it would be. It seems so simple! You get the right animals, the right habitat, they make eggs and then you move the eggs, right? Wrong. It’s incredibly complicated. Bringing people to the table with unique experience and expertise is how this project has gone as far as it has. And we will continue to bring new perspectives and new expertise to the table as we grow. So far, we’ve successfully moved eggs and seen pups hatch. These are huge milestones! And now we’re hopeful that the animals will thrive, that we’ll be tagging and releasing them in the coming months. But we don’t yet know the outcome of this work because nobody’s ever done this before.

When the Seattle Aquarium’s Ocean Pavilion opens in 2024, we will have the opportunity through that platform to show people these incredible animals that exist on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. We’ll also have a new platform to talk about this initiative to bring sharks and rays back from the brink of extinction: to not only tell people that there are almost 400 species of sharks and rays listed as endangered or critically endangered around the world, but also, here’s what we—all 70+ partners—are doing to turn that back around. I believe that will bring a sense of hope to people who visit.

And importantly, our visitors can take action in their daily lives to help sharks and rays throughout our one world ocean. We’re all connected.

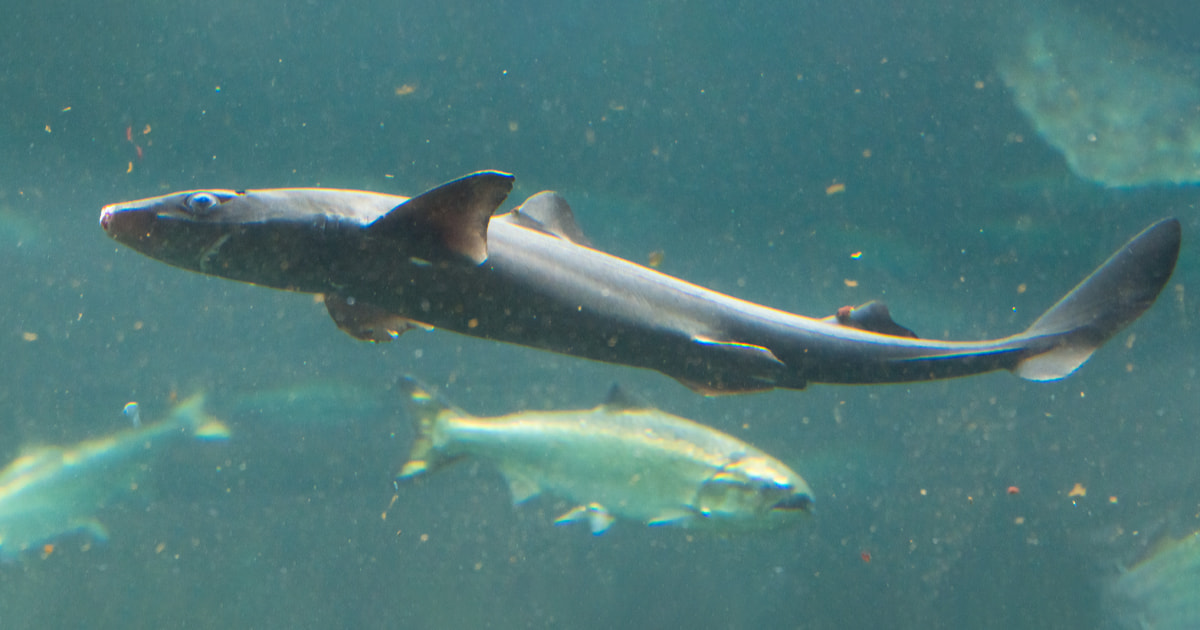

Senior Aquarist Chris Van Damme gingerly holds one end of a herring when feeding Elliott and the other Pacific spiny dogfish at the Aquarium. Dogfish—who are just as enthusiastic about meals as their furry namesakes—can chomp through their food with astonishing speed and force. As Chris shares in our interview, it’s just one of the many reasons these creatures inspire awe and affection from their caretakers.

Q: What do you find fascinating about dogfish?

A: You wouldn’t know it from their name, but dogfish are sharks. They’re a smaller species of shark, but like all sharks, they’re fast and sleek. They can turn on a dime. They’re immensely strong.

Dogfish are also record-setters. They have among the longest pregnancies of any animal: 22 to 24 months. (Fun fact: Dogfish pups are born ready to hunt!) They reproduce late in life—as late as their mid-30s for females—and they live long lives—80 years or more! They’re also remarkable travelers. One of my colleagues found a dogfish in California that had been tagged in Alaska.

Q: What surprises people when they visit dogfish at the Aquarium?

A: Visitors who hear there are sharks living in the Aquarium’s Underwater Dome sometimes mistake the sturgeon—a prehistoric-looking animal—for dogfish. Dogfish are understated. They can be hard to spot, and you’ve got to be patient.

Q: Where can you spot dogfish in the Underwater Dome?

A: In the mornings, unless it’s time to eat, you’ll often see them sitting on the sand at the bottom. At other times, you’ll see them swimming about midway up in the Dome.

Q: How does the Underwater Dome mirror how dogfish live in Puget Sound?

A: First, the water here comes directly from the Sound. Its temperature and salinity match their natural environment. Also, the Dome is a multi-species habitat just like in the wild. And, like in Puget Sound, there are open sandy bottoms where they can rest.

Q: What do dogfish at the Aquarium eat?

A: They eat a variety of herring, anchovy, clam, squid and shrimp. Their diet here mimics their diet outside the Aquarium, and that’s important to their health.

Q: Do they consider other fish in the Dome as prey?

A: No, we dive and target-feed them by hand every afternoon to minimize the possibility of that happening. (And since they are primarily scavengers, it’s a highly unlikely scenario anyway.) We also do a surface feed, where we drop larger pieces of food to the bottom for them.

Q: What is it like to hand-feed dogfish?

A: They have very sharp teeth, so it’s important to release the fish before they get too close!

Q: How do they eat outside the Aquarium?

A: They often hunt in packs like dogs—that’s why they’re called dogfish—and can eat their way through schools of fish. (Fun fact: Dogfish can hunt in packs of up to 1,000!)

Q: Are local dogfish populations healthy?

A: Thankfully, our local dogfish populations are healthy. In part that’s because we don’t have a targeted fishery here (meaning that we don’t eat them). Atlantic spiny dogfish, by contrast, are eaten in Europe. Our local dogfish populations are also managed by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration fisheries and by the Pacific Coast Management Fishery Council, which helps keep populations healthy.

That said, dogfish and all the animals living in our local waters are affected by what goes in our sewers and drains. (Tip: Learn how you can protect ocean health on our Act for the Ocean page.)

Q: What is a good pathway to a career like yours?

A: I studied oceanography at the University of Washington, which is a good field for studying the marine environment as a system. Oceanography combines physical, chemical, biological and geological science. If you’re specifically interested in working with sharks or helping to manage healthy shark populations, you should consider studying marine biology.

Q: As a diver, have you encountered dogfish outside of the Aquarium?

A: I can think of only a handful of times I’ve seen them while diving. Their senses are a lot better than ours. They see and hear us before we know they’re around, and they move fast.

They’re beautiful animals. It’s such a treasure and a treat to find one as a diver. It’s a gift.

Now that you’ve read Chris’s thoughts, check out our dogfish page to learn more about Elliott and the other dogfish at the Aquarium. On your next visit to the Aquarium, look carefully for Elliott in the Underwater Dome!

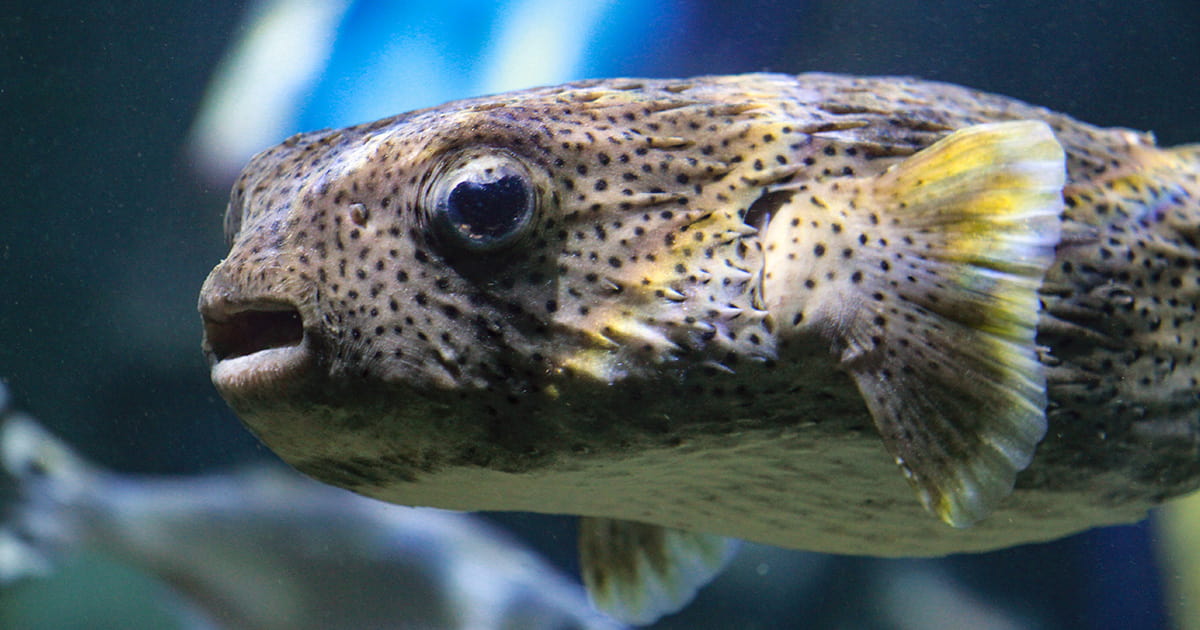

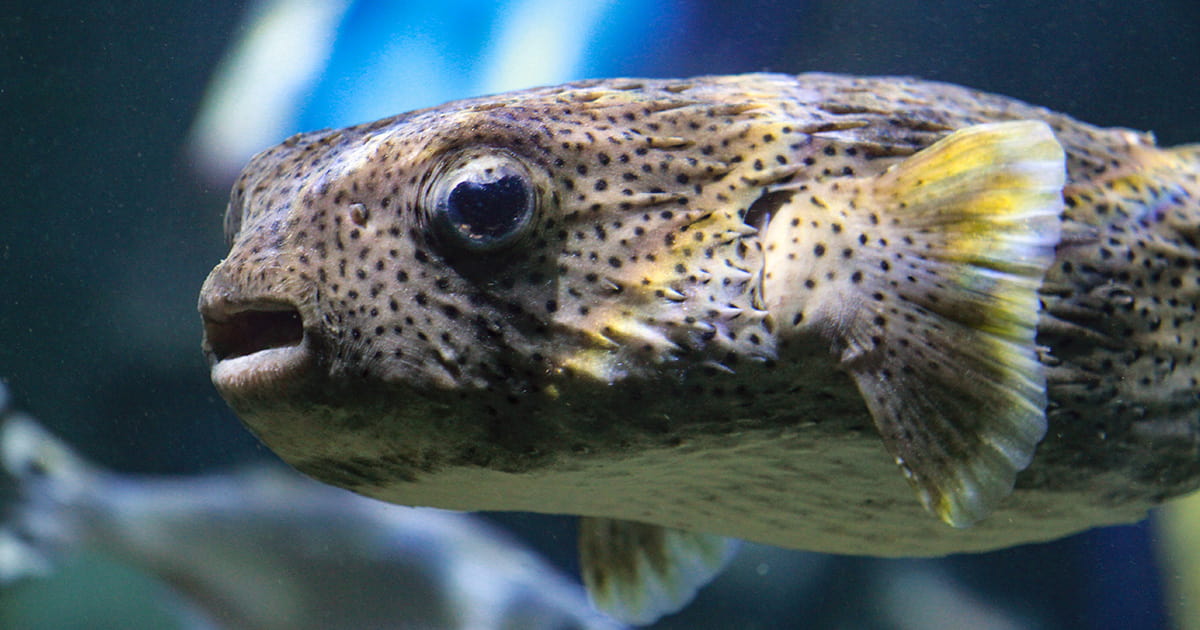

It’s fair to say that Senior Aquarist Alan Tomita knows more about porcupinefish than most people. An expert on tropical fish, he’s worked at the Seattle Aquarium for more than three decades. In this Q&A, Alan shares insights from his years spent caring for porcupinefish.

Q: What’s especially amazing about a porcupinefish?

A: Its superpower is intimidation. It can scare off predators by swallowing air or water to blow itself to double its size or more. Once it does, its spines—which are otherwise tucked away—transform into dangerous spikes.

Q: Does being puffed up change the way a porcupinefish moves or swims?

A: When a porcupinefish fully puffs itself up, its buoyancy is altered, often causing it to flip upside-down. But the upside-down fish ball has no problem bobbing along. Researchers and caregivers have noticed that a porcupinefish will sometimes puff up for no known reason, and not to the point where it loses buoyancy. This is believed to be the fish’s way of stretching its “puffer” muscles.

Q: In the wild, what kinds of predators are willing to take on a porcupinefish?

A: Because of its clever emerging spikes, the porcupinefish has few enemies. Its main predators are sharks, or fish that are large enough to swallow it whole.

Q: So large fish can safely swallow a porcupinefish?

A: Yes—if the predator can deflate it with its teeth, is big and fast enough to swallow it before it inflates, or is big enough to swallow it whole, even inflated.

However, a porcupinefish has a secret weapon hidden in its organs―a lethal toxin 1,200 times stronger than cyanide. This toxin doesn’t bother all fish and is most dangerous to mammals, including humans. In Japan, where porcupinefish (called fugu in that country) are considered a delicacy, fugu handlers must undergo special training to ensure the fish can be safely eaten.

Q: Are large fish the only threat to a porcupinefish?

A: No, its biggest threats are caused by humans. Since a porcupinefish will bite at whatever it finds floating in the water, it’s at risk for consuming plastic, which is dangerous to its health. People also like to collect porcupinefish, dry out the fish’s skin and inflate it for use as a Christmas tree ornament or lamp.

Q: Where do porcupinefish make their homes in the wild?

A: The porcupinefish—like many types of pufferfish—lives mainly in tropical waters around the world.

Q: What’s an average day in the life of a porcupinefish in the wild compared to at the Aquarium?

A: Porcupinefish living at the Aquarium spend most of their time hanging out, bobbing around and enjoying their own company.

In the wild, this solitary species will mostly sleep during the day and spend nighttime looking for food. It will “hang out” in caves and under ledges, swimming around mostly alone. Only juveniles seek the comfort of other porcupinefish.

A porcupinefish can live peacefully among nearly any type of fish. It’s not often threatened and therefore doesn’t need to use its defense mechanism unless something big comes along to scare it. Kōkala—the featured porcupinefish living at the Aquarium—currently lives in a habitat with about 200 other fish, and everything is simpatico.

Q: What does Kōkala eat at the Aquarium versus what she would eat in the wild?

A: In the wild, a porcupinefish enjoys a diet of hard-shell crustaceans, sea urchins, snails and other invertebrates.

At the Aquarium, Kōkala eats a diet mainly of clams, shrimp and squid, along with a jelly made of vegetable matter.

Q: Does she like her veggie gel?

A: Not really, but it’s good for her, and I can usually get her to eat one small square before she realizes what she’s gulped down.

Q: Isn’t that like a parent trying to sneak veggies into their child’s meal?

A: Exactly!

Q: What practical knowledge have you gained while working with porcupinefish?

A: When I’m caring for Kōkala, “care” is the key word. It’s not just the spikes that make being around a porcupinefish risky; her beak-like teeth also require me to proceed with caution. The first rule is to keep my fingers clear of her mouth. I’m always aware of how easy it would be to lose a finger.

Q: What led you to your career at the Seattle Aquarium?

A: I grew up in Hawai‘i, and my degree is in zoology from the University of Hawai‘i. I’d always wanted to work for a reputable aquarium and had my eye on Seattle for a while. When a position opened, I jumped on it, which turned out to be a smart move because I’ve been here for 33 years now!

Even though Kōkala is a loner, she doesn’t mind visitors! Plan a visit to the Seattle Aquarium, and maybe you’ll be lucky enough to see Kōkala stretch her muscles and puff herself up. You might even catch a glimpse of Alan caring for his favorite fish! Look for the puffers in our care in our Pacific Coral Reef and Tropical Pacific habitats. You can also discover more cool facts about these amazing animals on our pufferfish and porcupinefish webpage.

Take a deep dive into the world of our resident sea otters, Sekiu and her “roomie” Mishka! Our own Caroline Hempstead, lead animal care specialist for sea otters, gave us some great, insider-only details about this dynamic duo—as well as what it took for her to land her dream job as their caretaker.

Q: What’s an average day like for Sekiu and Mishka at the Aquarium, compared to an average day for a sea otter living in the wild?

A: For a sea otter, life at the Aquarium is a bit like a vacation compared to life in the wild, where an average day is spent working around the clock in order to stay fed, warm and healthy. Sea otters need to consume 25 percent of their body weight in seafood every day, so searching for food takes a lot of their time. They’re also constantly grooming their fur to retain its waterproofing and insulating qualities. Resting is key to survival as well, since searching for food and grooming burns an immense amount of calories—especially in the frigid waters of the Pacific.

Sekiu and Mishka have it easy by comparison! Their caretakers deliver every meal—nine per day, to be exact—by hand from dawn to dusk. Their diet consists of restaurant-quality seafood: Dungeness crab, Penn Cove mussels, squid, shrimp, capelin, herring, surf clam and butter clam. And, while they still need to spend time grooming their fur and resting like their wild counterparts, not having to hunt and collect their own food allows them more time to play. We offer enrichment in all different forms, from live food—they love to crack open and devour live oysters and manila clams!—to puzzle toys, ice treats and changes to their habitat like increasing water flow, direction or level, or even shifting them to a different habitat.

Fast fact: Sea otters need their incredibly dense fur to stay warm because, unlike other marine mammals like harbor seals, they don’t have a blubber layer for added insulation. They meticulously groom their fur by rubbing and blowing into it.

Q: What would you say are the top things people can do to help sea otters thrive in the wild?

A: First, purchase sustainable seafood, which keeps our oceans healthier and allows all marine species to prosper. Next, avoid single-use plastics and properly dispose of toxic chemicals and oils. Debris—whether it’s large or microscopic, solid or liquid—is harmful to any living species and in most cases end up in our waterways. Sea otters need a healthy ocean to survive so by taking care of our planet, we’re also taking care of sea otters everywhere, including Sekiu and Mishka at the Aquarium.

Fast fact: Every year, 11 million metric tons of plastics enter the ocean. That’s the equivalent of one garbage truck full of plastic going into the ocean every single minute of every single day! You can help keep plastic out of the ocean—visit our take action page to get started.

Q: You’re an ultimate insider when it comes to Sekiu and Mishka. What can you tell us about their likes and dislikes?

A: Just like us, or our pets at home, Sekiu and Mishka have their favorite and least favorite foods. If given the choice, Sekiu prefers Dungeness crab over any other food item and will devour a whole crab within minutes. It’s one of my favorite feeds to watch as she literally tears into the crab limb by limb without hesitation. All you hear is crunch, crunch, crunch!

Mishka’s favorite food is shrimp. She will often store shrimp tails in her armpits, so she can eat all of them at the end of her meal—saving the best for last!

Fast fact: Crab and shrimp provide the sea otters with good fiber, since they eat not only the meat, but also some of the shell—which helps them digest and process the food properly.

Q: It must be amazing to work so closely with Sekiu and Mishka. What was your career path?

A: After earning my bachelor’s degree in marine biology and having a few other fun and exciting jobs in the marine field, I decided to volunteer at the Seattle Aquarium. I was hired soon after and worked in all the animal life science departments. It soon became apparent that sea otters were becoming my favorite. With a couple more years under my belt, I landed my dream job—caring for the sea otters! I not only oversee the care of our sea otters, I also get to conduct sea otter surveys and research in Washington. And now I’ve been working here for 24 years. Time flies when you’re having fun!

Interested in a career like Caroline’s? Check out our careers page—and watch this video featuring some of our amazing animal care staff!

Q: If someone wanted to follow in your footsteps, what would you suggest as far as education and training?

A: I’d recommend an educational background in animal science, animal behavior or marine biology to get a better understanding of animal biology. And it’s essential to obtain hands-on work experience in a zoo or aquarium setting. You can start like I did and become a volunteer, or apply for an internship to get your feet wet with our sea otters.

Bonus video! Learn more about sea otters as Caroline answers questions from Seattle Aquarium members.

Porcupinefish can inflate their bodies by swallowing water (or air), becoming rounder and doubling in size. This makes them appear larger, scaring off potential predators.

A porcupinefish is covered with sharp spines (up to 2 inches long) that lay flat against its body. When it puffs up, the spines stick out and become sharp spikes (like a porcupine)!

While the two fish are often collectively referred to as pufferfish, they are indeed distinct. Other pufferfish have soft spines that are unnoticeable in some species, but only the porcupinefish has sharp, protective spines.

When a porcupinefish puffs itself up, the modified buoyancy causes it to turn upside down. When the danger has passed, a porcupinefish will deflate, turn right-side up and continue on its way.

In many parts of the world, porcupinefish and puffers are served in high-end restaurants even though their internal organs contain a neurotoxin that’s 1,200 times stronger than cyanide.

Taking shorter showers, or showering less frequently, is one way to conserve water and reduce energy use, which benefits all the animals that live in the ocean.

Through a new campaign developed and produced by the nonprofit Sachamama, the Seattle Aquarium is featured alongside other prominent locals engaged in efforts to address threats to the health of Puget Sound—and the impact those threats could have on the vitality of our communities and economy.

Sachamama is a conservation organization grounded in Latinx cultural heritage and working to build support for a clean energy economy for all, and cultivating sustainable attitudes, behaviors and lifestyles. (Sachamama is a word in the Quechua language, which is spoken in the Amazon and South American Andes regions—it means “mother jungle.”) One of their key initiatives involves protecting the health of our ocean and inspiring conservation action and advocacy throughout Latinx communities.

Now we, along with several others, have lent support to Sachamama on a series of editorials focused on the health of Puget Sound and connections to local communities—including the environmental challenges that threaten our ecosystem and the well-being of our region’s residents.

The series showcases five local champions, their connections to the Sound and the environmental benefits the Sound provides for current and future generations. It’s part of a larger effort in support of 30×30, a global initiative to protect and conserve 30% of land and waters, including the ocean, by 2030.

Seattle Aquarium Senior Manager of Ocean Policy Nora Nickum was featured in Sachamama’s first published editorial, devoted to microplastics. The editorial highlighted our research into the prevalence of microplastics in Elliott Bay as well as partnering with the Plastic Free Washington/Washington Sin Plástico Coalition to pass SB 5323 and SB 5022, both of which will reduce plastic pollution in our local waters. Nora also participated as a panelist in Sachamama’s Facebook Live event focused on microplastics in Puget Sound. Seattle Aquarium Empathy Fellow Gabi Esparza was featured in the editorial as well, describing the important role of empathy in marine conservation and the Aquarium’s initiatives to increase access and inclusion throughout the community.

Other champions featured in the series include Candace Penn, climate change ecologist with the Squaxin Island Tribe Natural Resources Department; Luis Navarro, director of workforce development for the Port of Seattle; Ruby Vigo, coordinator for the Duwamish River Community Coalition; and Noe Rivera, an owner of Rivera’s Shellfish. All are working, in various ways, to ensure that Puget Sound can continue to be a source of life and livelihood for our communities and future generations. We thank Sachamama for their leadership on this exciting project—and inviting us to participate in it.