Farewell to Barney

It’s a very sad day at the Seattle Aquarium as we say goodbye to Barney the harbor seal. As we shared last September, in a story commemorating his birthday, Barney was quite old: At 39, he was roughly the equivalent of a 100-year-old human—and one of the oldest known harbor seals in human care.

Beloved by many, Barney will be deeply missed and remembered always with love.

Director of Animal Health Dr. Caitlin Hadfield and members of our veterinary and animal care teams had been working closely with Barney for years, making sure he was as happy and comfortable as possible. Just like many elderly humans, he developed some age-related health issues over time but overall had been doing well.

Recently, however, he showed an acute decline. Based on his prognosis and how he was feeling—his quality of life—the team made the difficult decision to humanely euthanize him on the morning of March 14. “We know that many in the community will join the Aquarium’s staff and volunteers in mourning this loss. Barney will be remembered and missed,” says Aquarium President and CEO Bob Davidson.

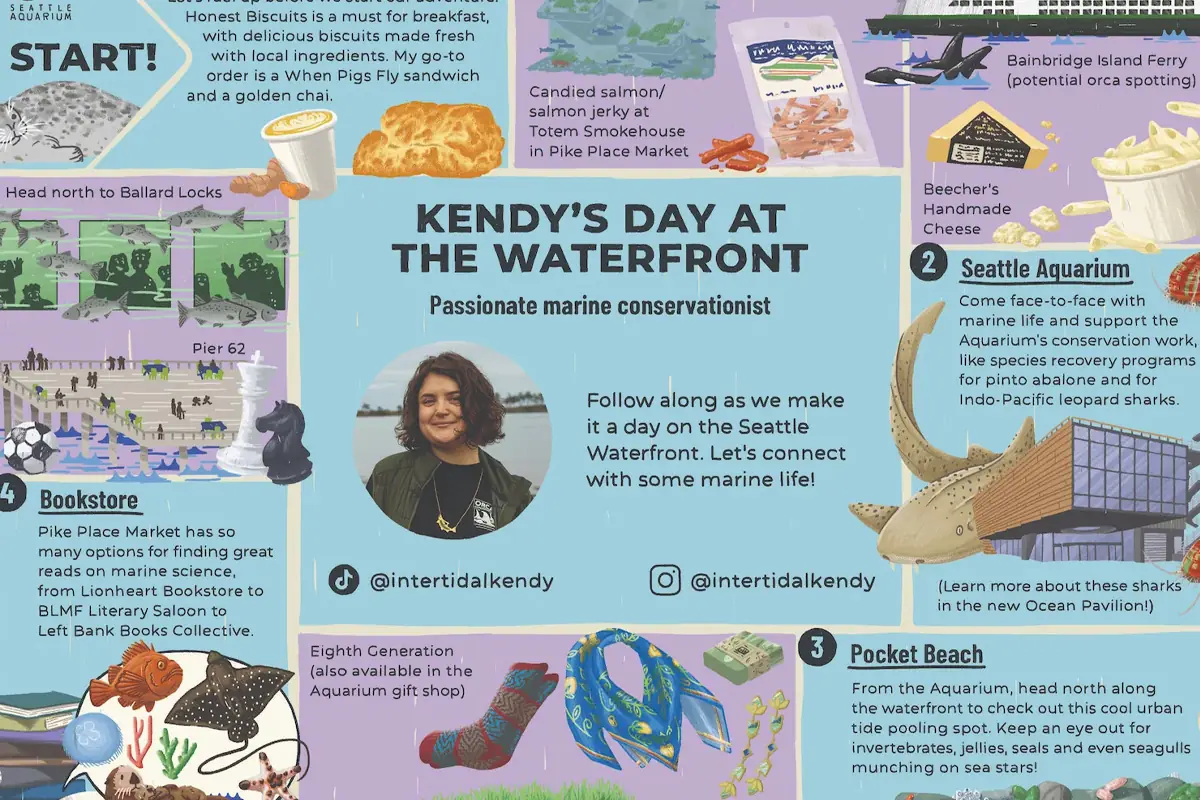

Barney getting ready to tuck into his 39th birthday ice treat on September 14, 2024.

Barney was the first harbor seal to be born here at the Aquarium, in 1985. He shaped many caregivers over his long life and was cherished by all, particularly for his easygoing and inquisitive nature. “I knew Barney for 19 years and my appreciation of him only grew as time passed,” comments Animal Care Specialist Cheryl Becker. Dr. Caitlin Hadfield, who had worked with Barney since joining the Aquarium in 2017, notes, “Barney had great trust in his human caregivers and his home. He had a number of health concerns over the last few years and we learned a lot from each other. I’m proud of the care the animal care staff provided, and that we were able to help ensure that his end of life was peaceful.”

Barney will be remembered as a wonderful, one-of-a-kind ambassador for the Seattle Aquarium. “He inspired a stronger curiosity about the ocean in millions of people—a curiosity that inspired action for conservation of our marine environment,” says Bob Davidson.

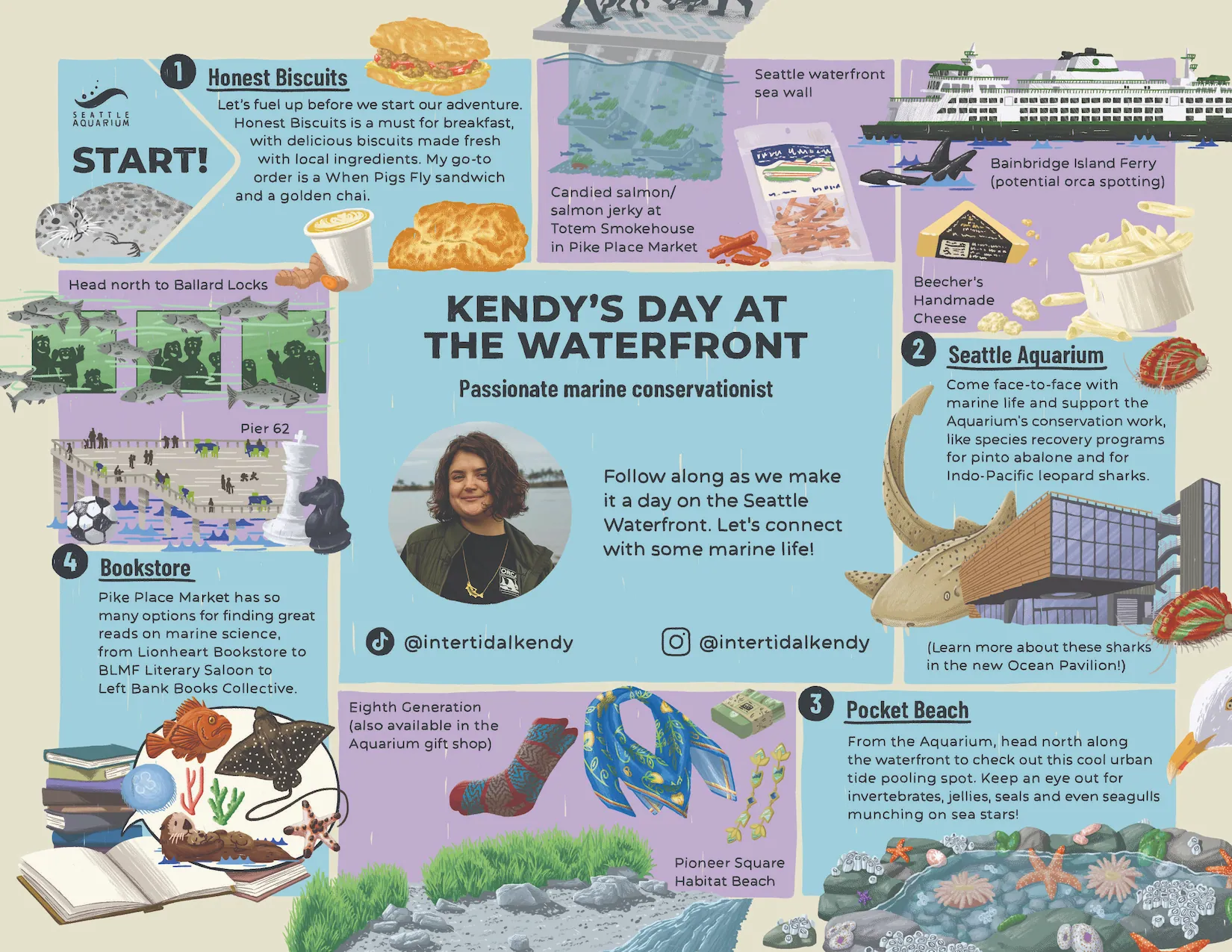

Even at his advanced age, Barney clearly relished his favorite foods.

“In my childhood bedroom is a box filled with my most precious memories. Paramount among them is a series of photos of me as a child at the Seattle Aquarium, including one where I’m smiling beside a harbor seal who happens to be Barney! In many ways, subtle and overt, he played a role in shaping who I am. Choosing a career in animal care, grounding my purpose in life to bring people’s focus and empathy to conservation, staying committed to being silly in my age and, of course, only eating what I want. In the two decades since the photos were taken, I had the immense pleasure of playing a small role in caring for Barney. Thank you, Barney, for watching me grow, encouraging me to learn, allowing me to try to pay it all back in fish—thank you Barney, thank you.”

——Cyren Guerrero, Life Sciences/Operations relief

Barney was a beloved icon here at the Aquarium and, over his nearly 40 years, touched the hearts of countless visitors, volunteers and staff. Says Supervisor of Birds and Mammals Mariko Bushcamp, “Barney and I were the same age and I knew him for nearly half my life.” She speaks for all of us when she adds, “You’ll leave a big hole—but thank you for all the memories, Barn.”

Barney enjoying a moment in the sun.