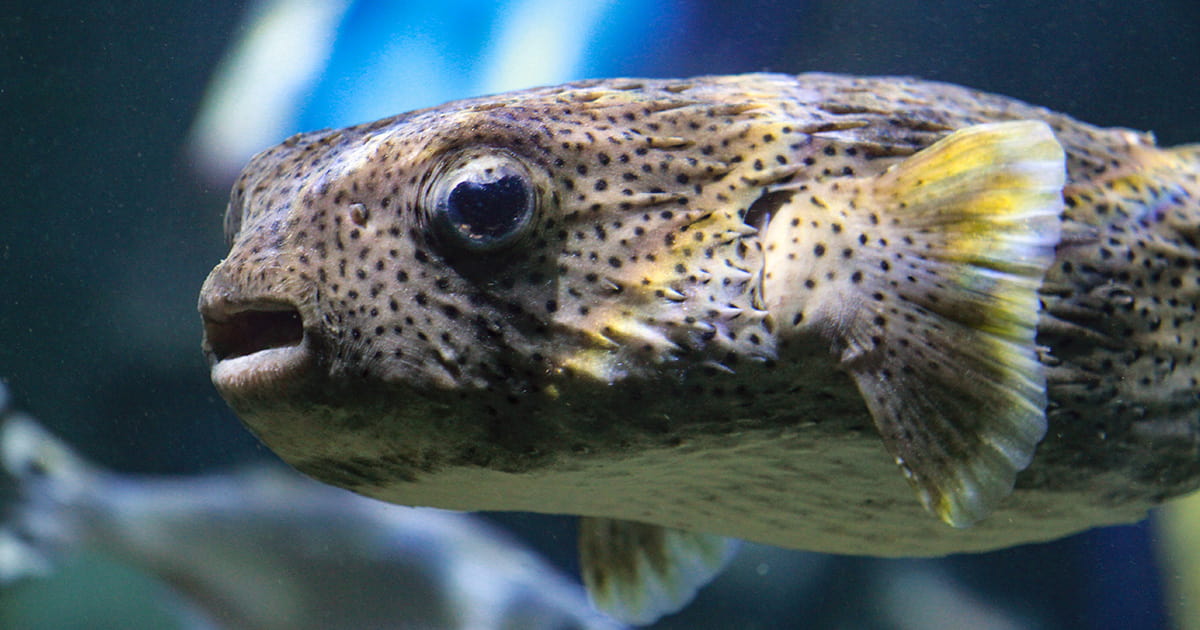

What is it like to care for a porcupinefish? Our senior aquarist weighs in

It’s fair to say that Senior Aquarist Alan Tomita knows more about porcupinefish than most people. An expert on tropical fish, he’s worked at the Seattle Aquarium for more than three decades. In this Q&A, Alan shares insights from his years spent caring for porcupinefish.

Q: What’s especially amazing about a porcupinefish?

A: Its superpower is intimidation. It can scare off predators by swallowing air or water to blow itself to double its size or more. Once it does, its spines—which are otherwise tucked away—transform into dangerous spikes.

Q: Does being puffed up change the way a porcupinefish moves or swims?

A: When a porcupinefish fully puffs itself up, its buoyancy is altered, often causing it to flip upside-down. But the upside-down fish ball has no problem bobbing along. Researchers and caregivers have noticed that a porcupinefish will sometimes puff up for no known reason, and not to the point where it loses buoyancy. This is believed to be the fish’s way of stretching its “puffer” muscles.

Q: In the wild, what kinds of predators are willing to take on a porcupinefish?

A: Because of its clever emerging spikes, the porcupinefish has few enemies. Its main predators are sharks, or fish that are large enough to swallow it whole.

Q: So large fish can safely swallow a porcupinefish?

A: Yes—if the predator can deflate it with its teeth, is big and fast enough to swallow it before it inflates, or is big enough to swallow it whole, even inflated.

However, a porcupinefish has a secret weapon hidden in its organs―a lethal toxin 1,200 times stronger than cyanide. This toxin doesn’t bother all fish and is most dangerous to mammals, including humans. In Japan, where porcupinefish (called fugu in that country) are considered a delicacy, fugu handlers must undergo special training to ensure the fish can be safely eaten.

Q: Are large fish the only threat to a porcupinefish?

A: No, its biggest threats are caused by humans. Since a porcupinefish will bite at whatever it finds floating in the water, it’s at risk for consuming plastic, which is dangerous to its health. People also like to collect porcupinefish, dry out the fish’s skin and inflate it for use as a Christmas tree ornament or lamp.

Q: Where do porcupinefish make their homes in the wild?

A: The porcupinefish—like many types of pufferfish—lives mainly in tropical waters around the world.

Q: What’s an average day in the life of a porcupinefish in the wild compared to at the Aquarium?

A: Porcupinefish living at the Aquarium spend most of their time hanging out, bobbing around and enjoying their own company.

In the wild, this solitary species will mostly sleep during the day and spend nighttime looking for food. It will “hang out” in caves and under ledges, swimming around mostly alone. Only juveniles seek the comfort of other porcupinefish.

A porcupinefish can live peacefully among nearly any type of fish. It’s not often threatened and therefore doesn’t need to use its defense mechanism unless something big comes along to scare it. Kōkala—the featured porcupinefish living at the Aquarium—currently lives in a habitat with about 200 other fish, and everything is simpatico.

Q: What does Kōkala eat at the Aquarium versus what she would eat in the wild?

A: In the wild, a porcupinefish enjoys a diet of hard-shell crustaceans, sea urchins, snails and other invertebrates.

At the Aquarium, Kōkala eats a diet mainly of clams, shrimp and squid, along with a jelly made of vegetable matter.

Q: Does she like her veggie gel?

A: Not really, but it’s good for her, and I can usually get her to eat one small square before she realizes what she’s gulped down.

Q: Isn’t that like a parent trying to sneak veggies into their child’s meal?

A: Exactly!

Q: What practical knowledge have you gained while working with porcupinefish?

A: When I’m caring for Kōkala, “care” is the key word. It’s not just the spikes that make being around a porcupinefish risky; her beak-like teeth also require me to proceed with caution. The first rule is to keep my fingers clear of her mouth. I’m always aware of how easy it would be to lose a finger.

Q: What led you to your career at the Seattle Aquarium?

A: I grew up in Hawai‘i, and my degree is in zoology from the University of Hawai‘i. I’d always wanted to work for a reputable aquarium and had my eye on Seattle for a while. When a position opened, I jumped on it, which turned out to be a smart move because I’ve been here for 33 years now!

Even though Kōkala is a loner, she doesn’t mind visitors! Plan a visit to the Seattle Aquarium, and maybe you’ll be lucky enough to see Kōkala stretch her muscles and puff herself up. You might even catch a glimpse of Alan caring for his favorite fish! Look for the puffers in our care in our Pacific Coral Reef and Tropical Pacific habitats. You can also discover more cool facts about these amazing animals on our pufferfish and porcupinefish webpage.