Category: Uncategorized

Quiz: Which marine species is your cozy season alter ego?

Quiz: Do you know the Spanish names of ocean animals?

Dive down memory lane with us to celebrate Barney’s 40th birthday!

Editor’s note: This story was originally published in September 2024 for Barney’s 39th birthday, as he approached the human equivalent of 100 years old. Barney passed in March 2025. To celebrate his life and legacy, we’re republishing this story on what would have been his 40th birthday.

Barney the harbor seal was born right here at the Seattle Aquarium on September 14, 1985! And he’s been stealing the hearts of staff and guests alike ever since, while inspiring millions to help protect his beloved and charismatic species.

In his golden years, Barney enjoyed the simple things in life, like a nice nap in the sunshine, getting his teeth brushed daily and eating some of his favorite snacks, including all things fish. He was also a fan of his birthday celebrations, as you’ll see in the photos below. Dive down memory lane to revisit some of those celebrations with us as we commemorate Barney’s extraordinary life!

Centennial celebration—happy 39th, Barney!

According to the Association of Zoos & Aquariums (AZA), of which we’re proud to be an accredited member, the median life expectancy for harbor seals in zoos and aquariums is about 25 years. At 39, Barney has lived well beyond that. In fact, his biological age is about the equivalent of a 100-year-old human!

Give him—and his caretakers—some love on our Facebook or Instagram to mark the occasion.

38 years young!

Barney’s 38th birthday bash was complete with a “cake” made from ice and 38 frozen fish!

37 looks good on you

We welcomed harbor seal Casey earlier in 2022, and all three “roomies”—Barney, Hogan and Casey— dug into a delicious, fish-filled ice treat together.

Having his cake and eating it too

Barney rang in his 36th birthday by tucking into a towering ice treat “cake.”

Pandemic party

While we couldn’t invite the public to celebrate with Barney because of our temporary, pandemic-related closure, our incredible animal care team made sure he felt the birthday love.

Just another enriching birthday

Animals at the Aquarium receive enrichment every day (read more about it on our webpage). Special occasions, like Barney’s 30th, give our animal care team a fun reason to get creative with it.

28 and looking great!

In 2013, Barney celebrated his birthday with cake in his habitat’s new haul-out space*! Generous support from people like you allowed us to renovate and expand the harbor seal habitat back then.

*What’s that? Space that the seals use to go onto dry land to nap, groom, cooperatively participate in their own health care and, in Barney’s case, eat a birthday treat.

Your gift today will make a difference too: Please consider a donation of $19.85, $39 or any amount on behalf of Barney’s birthday!

Awww, you shouldn’t have

Shown here in the habitat’s previous haul-out space, Barney looks ready to devour the ice treat that our animal care team prepared for him.

Stealth celebration

What’s better on your 26th birthday than a delicious ice treat, just waiting for you to notice it as you casually swim by?

Blow out the candles!

Here’s a throwback to Barney’s 25th! Our animal care team went all out with an ice treat complete with “candles” for him to crunch and munch.

Baby Barney’s birth day

Photo: Seattle Post-Intelligencer

How’s this for a sweet, vintage photo of newborn Barney alongside his mom, Clyde? For perspective on how long ago that was in terms of other Pacific Northwest icons, Barney was born the same year that downtown Seattle’s tallest skyscraper, Columbia Center, opened; two years before the band Nirvana was formed; and 15 years before the Kingdome was demolished. Just our humble opinion, of course, but we think he’s the best and most charming icon of the bunch. Happy, happy 39th to beloved Barney!

Quiz: Plan your perfect day on the Seattle Waterfront

Remembering Dive Safety Officer Jeff Christiansen

Editor’s note: We at the Seattle Aquarium were deeply saddened to learn of the recent passing of Jeff Christiansen—an extraordinary person, lifelong diving aficionado and valued staff member here at the Aquarium for nearly 40 years before his 2021 retirement. Jeff died on August 25 after experiencing a medical emergency underwater during a night dive.

To celebrate his life and honor some of his many contributions toward advancing our conservation mission, we’re resharing a web story we published as Jeff retired from his long career with us. Our hearts are with his grieving family, friends and diving community.

Celebrating the Seattle Aquarium career of retiring Dive Safety Officer Jeff Christiansen

“You’re so lucky when you can make your passion your vocation,” says Jeff Christiansen, who retired on March 12, 2021 after a career at the Seattle Aquarium that began nearly 40 years ago. Jeff’s passion? Scuba diving. “It’s the closest you can get to another world without going into space,” he says.

Jeff’s love of diving started before he even entered elementary school in Aurora, Colorado. “I’ve been scuba crazy my whole life,” he laughs. “I learned to swim on the bottom of the pool when I was 4 years old. I grew up watching Sea Hunt and, for Halloween, I’d dress as a diver wearing a modified cat costume with oatmeal canisters on my back as oxygen tanks.”

Jeff generously shared his knowledge and expertise with the Seattle Aquarium and diving communities.

When Jeff was 12, in 1968, his family moved to Seattle—and Jeff took his enthusiasm for diving to a whole new level. “My parents signed me up for scuba diving lessons, and I was certified as a junior scuba diver at age 12½,” he notes. “I helped start a scuba diving club at school. We lived on Three Tree Point near Burien, so I could walk down the block and into the water,” he adds.

As college approached, Jeff researched careers that could involve diving and landed on fisheries sciences. He became a Seattle Aquarium volunteer just a year after we opened, landing a slot in what was then called the Puget Sound Fishes exhibit in 1978. Two years later, he graduated from college and became a member of the Aquarium’s first pool of volunteer divers.

“It was a career of coming to fun, not coming to work, every day.”

Jeff joined our staff in 1982, in a role called bio guard, which was, “half life sciences and half security,” he says. His shift ran from 7pm to 3am and, despite the challenging hours, “It was a lot of fun—a very diverse position and a great way to learn where everything was at the Aquarium and how it worked,” he comments. After stints as an exhibit technician and biologist (and transitioning to working at the Aquarium during the day instead of through the night), Jeff became our assistant dive safety officer in the mid-1980s and eventually took over as the lead dive safety officer—a position he held until his retirement.

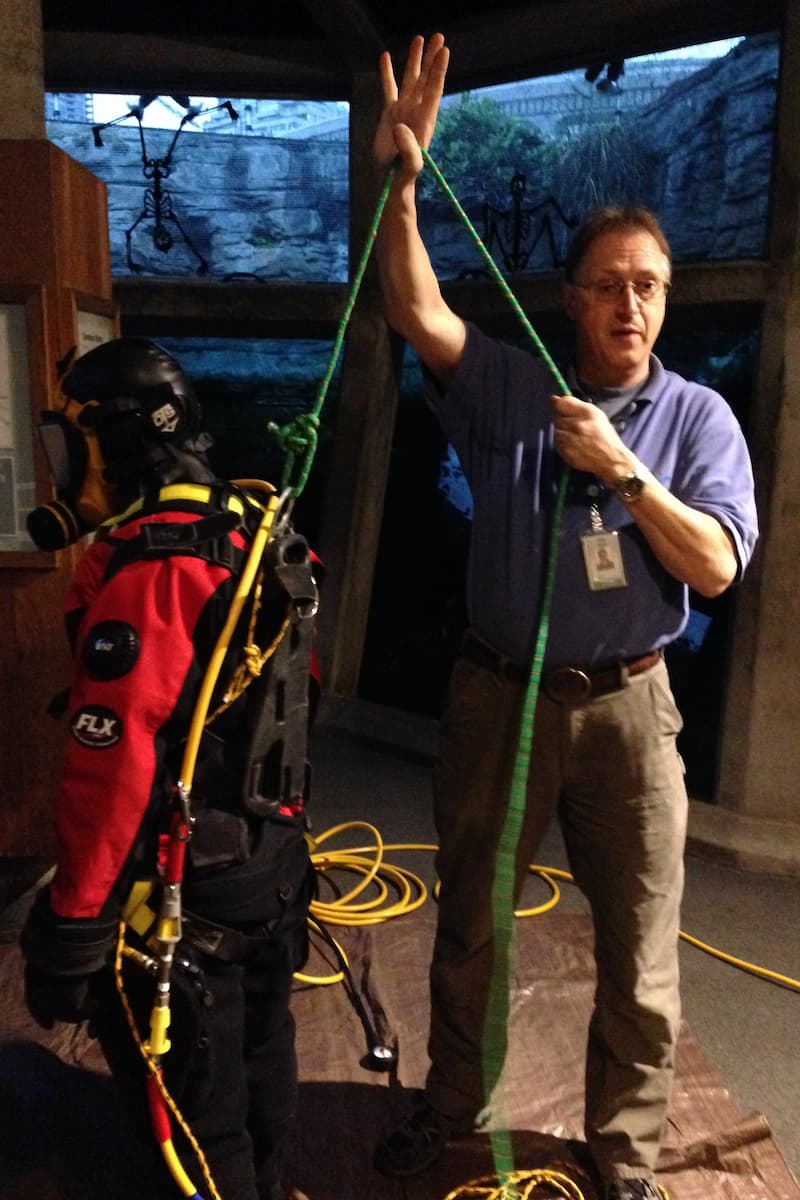

Jeff Christiansen leading a dive safety demonstration at the Seattle Aquarium.

Hearing Jeff describe highlights of his career at the Seattle Aquarium creates a quick understanding of why he describes it as “coming to fun.” He helped lead trips to Neah Bay, visiting sites that sit within Makah Tribe waters (we operate under a permit from the Tribe to enter their land/waters) and serving as the primary operator of the Aquarium’s boat. “Some of the sites we’re still visiting were found with a chart, compass and an old-school, flashing fishfinder,” he laughs. “It was a real test of our navigation skills.”

He was also closely involved in our sixgill shark research during the extraordinary era when these amazing animals were regularly spotted below the Aquarium’s pier. “Staying at the Aquarium late into the night, seeing a shark cruise by, and then having the opportunity to tag one underwater—those were some of the most exciting dives of my life,” he notes.

Jeff in his element, diving with underwater camera equipment.

The most fun of all? “It’s a tie between diving in the Underwater Dome and working in the Puget Sound Fish habitats before the Aquarium opens,” Jeff says decisively. “You put on the music of your choice, do your work as a professional fish janitor and get the privilege of seeing what happens as the fish wake up,” he smiles. “Watching fish for 10 minutes will solve most problems.”

“I like seeing what we’ve built.”

The Seattle Aquarium has grown and changed in many ways since those very early days when Jeff joined us as a volunteer—with many more exciting changes yet to come. “The Aquarium has only gotten better and better over the years,” he says. “It’s truly a jewel on the waterfront, doing the important job of connecting what’s going on above the water with what’s happening below the surface.”

Jeff diving off of the Big Island of Hawai‘i with then-Associate Curator of Fish & Invertebrates/Assistant Dive Safety Officer Joel Hollander, who has since become our dive program manager.

He adds, “The Aquarium is so much more than just our physical footprint. Research, conservation education, community outreach, advocacy…it’s been great to see it going in those directions and I’m looking forward to seeing what the future holds.”

From the bottom of our hearts, we thank Jeff for his remarkable years of service to the Seattle Aquarium and our mission of Inspiring Conservation of Our Marine Environment. He will be greatly missed—and we wish him all the underwater adventure he could dream of in his well-deserved retirement.

“I recognize what we’re capable of and what’s at stake, because there’s still so much we can do:” Q&A with President & CEO Peggy Sloan

Gift shop buyer. Baby bald eagle caretaker. Nature adventure leader. International sailboat crewmember. Chief animal operations officer. Education curator. President & CEO.

What do these roles have in common?

Peggy Sloan, who joined us as our new president & CEO in May, has held each of them—and others!—over the course of her storied career. She recently sat down to talk about the road that brought her here, what she’s learned along the way and her vision for the Seattle Aquarium and our conservation mission. (Missed the announcement about her arrival? Check out our press release.)

Seattle Aquarium President & CEO Peggy Sloan.

Q: What experiences did you have as a young person that created a sense of connection to the natural world and ocean?

A: I think my curiosity about nature and animals was innate. I grew up in an urban-suburban environment with pockets of wildlife—wherever there were animals and trees, I was out in it.

Q: Did you grow up thinking that you were going to do something with animals?

A: I had no idea except that I wanted to be happy. And what made me happy was being in nature and helping animals.

Q: What drew you to a career in marine conservation?

A: That’s a long story with a lot of twists and turns along the way! But where it started was pursuing environmental science in college, because that was the major with the most field courses and time outside.

I took classes in marine science. I was also working and had many different jobs, including one with an organization called Project U.S.E., where we brought urban youth into the outdoors for transformative experiences through nature and community.

My first job after graduation was like my little-kid dream: raising and releasing bald eagles for the endangered non-game species program in New Jersey. After my first season, they offered me a permanent job. At the same time, Project U.S.E. offered me a job leading a new coastal canoeing program. That’s the one I took. It was a very conscious choice that we have to work with people to protect nature.

After two years, I recognized that what I was doing was working for people in nature, not working for nature—and that I had a different calling. Because I didn’t need housing during my time with Project U.S.E., I’d been able to save some money. I took what I had, which was a bicycle and camping gear, and bought a ticket to New Zealand for a few months to see some of the world and figure out what was next.

On the last leg of the trip, I got stuck in a rainstorm and pulled over in a little port town where circumnavigating sailboats were looking for crew. I’d never sailed before but I’d always wanted to. I thought I’d extend my travel by a few weeks and instead sailed for the next 18 months, ending back in the U.S.

“That was what solidified marine conservation for me: How small the planet is. How much of it is covered by water. How vulnerable the ocean is, even though it seems so vast.”

At the end of it all, when I got back to the U.S., I knew I had to work for the ocean. But what that looked like, I didn’t yet know.

Working and living in the Pacific Northwest helped Peggy fall in love with our unique region. Photo: Susan Sommer (nee Beeman).

Q: What a story! What happened next?

A: I got a job here in Seattle working in the Bering Sea as a scientific observer for commercial fisheries. I fell in love with the Pacific Northwest and decided to pursue research and education for the ocean.

I thought, “I will run a boat, I will do research and education, and I will do it in the Pacific Northwest because I love it here.”

I had a job lined up to operate a boat for three months in the Florida Keys and went there to get my captain’s license. I got it—and in the process found a calling where it wasn’t required. I started working in a marina and, on my days off, volunteered at a place called the Dolphin Research Center (DRC).

“And that's where the switch turned on. I saw the intersection between what I wanted people to care about and what they did care about. They came through the door just wanting to see dolphins and were absolutely transformed in their receptivity to connecting with and caring about nature.”

Q: And we’re only in 1993! What happened over the next 30+ years?

A: I took the first job available at DRC, which was the gift shop buyer, and ended up leaving as director of education. A lot happened in the interim! But throughout my time there, I recognized what I really wanted to know about was, “How are we activating people in the conservation space?”

After eight years with DRC, I started graduate school and took a job as the education curator at Brevard Zoo in Florida. This position introduced me to the broader community of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and the possibility to amplify conservation impact through broad collaboration. However, after two years, I knew my focus needed to be marine. I had the opportunity to go to North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher as their education curator, which I did for seven years and then became the aquarium director for another nine. I also finished my graduate degree in marine biology at UNC-Wilmington.

In 2018, I welcomed the opportunity to join the John G. Shedd Aquarium in Chicago during a time of major transformation. I wanted to understand how to reach people in urban settings—where most humans live—and Shedd created an ambitious plan to do so.

I’d probably still be there if it weren’t for the opportunity here. As much as I loved the work and will always love the Shedd Aquarium, I missed the ocean.

Q: What drew you to the president & CEO role at the Seattle Aquarium?

A: The sense of place, the potential for impact, the ethos and the talent.

Throughout my career, once I became connected with the AZA community, the Seattle Aquarium was very much in my sphere of work partners. This aquarium has always punched above its class—the culture and community here are really effective and innovative. And when I’m in conversation with the board, it’s clear that the most important thing to them is delivering on the conservation mission. We also have two new buildings, the off-site Animal Care Center and the Ocean Pavilion—and a whole new waterfront of opportunity.

Peggy meeting with a group of Seattle Aquarium volunteers.

Q: What initiatives would you like to move forward during your time here?

A: I want us to be operationally stable, meaning that people want to work here, and stay, because we are effectively delivering on our mission and they’re excited about what’s next: deepening our impact. I want us to lean in to what we’re good at and combine our strengths in such a way that we are moving the needle on marine conservation with a highly engaged, talented and valued team.

Q: What does deepening impact look like to you?

A: Deepening impact means that the changes we’re working to achieve come to fruition: more critical marine areas are protected, effectively—creating nature solutions to global environmental threats, like warming seas, while simultaneously leading to more species recovery—because more people, all people, value nature—because we need it to live on a habitable planet.

Q: Last big question: Why are aquariums important?

A: The Seattle Aquarium is a conservation organization and we’re preaching to the congregation more than the choir. For example, The Nature Conservancy, World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International and other great and well-established conservation organizations would love to have our platform. The people that are engaged with those organizations—who are doing tremendous work—are already in the choir. They’ve joined up because they already value nature.

Our audiences are not necessarily there. We have this incredible opportunity to reach people where they are. That’s why we call aquariums free-choice learning environments, right? People may choose to come here because their kids want to see sharks or otters or an octopus. Or they may simply want something to do on a rainy day. And that gives us a chance to reach them.

Aquariums are one of most accessible and best ways that we have of introducing people and getting them connected to the ocean in a meaningful way. That’s why some of the most important roles in the Aquarium are probably the front-line greeters who encourage people to go to the touch pools or the harbor seal habitat—“You’ve gotta see XYZ!” They feel important, seen and heard. They have fun, and want to come back and want their friends to come too. And they want sea otters to be happy for the rest of their lives.

Q: Last question for real: What’s your favorite invertebrate and why?

A: That’s one I can’t answer because it’s whichever one is in front of me—the one that I’m getting to see and experience. I saw two opalescent nudibranchs in the touch pools this morning. The fact that they just come in with the water from Elliott Bay, just below our pier—it’s absolutely magic and our guests think so too. From moments like that, it’s a quick jump to, “Oh my gosh, we have to save the ocean.”

Can you spot an opalescent nudibranch on your next visit to the Aquarium?

Ready to learn more about what you can do to help protect the one world ocean we all depend on? Visit our Act for the Ocean webpage and plan your next visit to the Seattle Aquarium! You might even spot Peggy admiring the nudibranchs at the touch pools.

Quiz: Are you an Oatmeal or a Kuda?

Getting to know nudibranchs

Summer is here! And you’ve still got time to meet Seattle Aquarium beach naturalists on local shorelines to discover the amazing animals that live in the intertidal zone, aka where the water meets the land between high and low tide. (Check the schedule here!)

Nudibranchs are among the many fascinating creatures you may encounter on the beach at low tide. You can also get to know some nudibranch species in a number of habitats at the Seattle Aquarium.

But wait! Are you wondering, “What’s a nudibranch?” It’s a fair question. You may also be thinking, “How do I pronounce that word?” We can help with that too!

Is that a lemon nestled into the kelp? Almost! It’s a species of nudibranch called a sea lemon. It’s among the nudibranchs you can see and learn about at the Aquarium—and you may be able to spot one on a local beach at low tide as well.

Nudibranchs 101

First things first: Nudibranchs are members of the sea slug family. They’re mollusks, related to bivalves (meaning animals with two shells) like clams, mussels and oysters, as well as single-shelled animals like chitons.

But unlike those cousins, nudibranchs don’t have shells.* So you could technically think of them as naked sea slugs. After all, their name does start with the word “nude” (minus the “e”)!

All kidding aside, the name nudibranch means “naked gills.” It refers to the external gills or feathery-looking appendages that many nudibranch species display on their backs.

And how do you say their name? NEW-de-brank (with the same “a” sound as “tank”). If you’re admiring more than one of these fascinating creatures, it’s NEW-de-branks (never NEW-de-branches!).

*Well, the adults don’t. Larval nudibranchs have shells but shed them as they mature.

You can also get to know the opalescent nudibranch when you visit the Seattle Aquarium.

A deeper dive

Scientists estimate there are over 3,000 nudibranch species. They’re found worldwide—in cooler, temperate waters like those in Puget Sound, tropical waters like the Coral Triangle and even the frigid waters of the Arctic and Antarctica. They live at depths ranging from the intertidal zone to over 2,000 feet below the surface. And they come in incredible variety of shapes, colors and sizes, from a fraction of an inch to about the size of a football.

That’s a lot of differences! But the majority of nudibranch species share some common characteristics—in addition to the soft bodies, lack of shells and external gills that inspired their common name, that is.

For one, most nudibranchs have a pair of sensory tentacles on their heads, called rhinophores, that help them detect chemicals in the waters (similar to how your nose helps you detect odors in the air). They’re carnivores, preying on animals including sponges, barnacles, anemones—even other nudibranchs! And they have both male and female reproductive organs.

It’s easy to see why the common name for this nudibranch species is “shaggy mouse!”

See for yourself—and lend a helping hand

There’s much more to learn and love about nudibranchs, and the Seattle Aquarium is a great place to start. You can chat with our volunteer naturalists on the beach this summer or visit the Aquarium to strike up a conservation with one of our knowledgeable interpreters—just look for the folks in blue shirts!

And, no matter how far away you are from the ocean, you can make a difference for the animals that live there, including nudibranchs. A few ideas: Contact your legislators to urge support for legislation that protects ocean health. Use public transportation, fly less and limit your use of single-use plastics. Looking for other ideas? Volunteer naturalists on the beach and interpreters at the Aquarium are a great source for those too! You can also check out our act for the ocean webpage.

Gay whales and trans fish: celebrating queerness in the ocean

Pride Month is a great time to appreciate queerness in all its powerful beauty in our human communities. But just like in cities and towns across the world, the ocean is abundant with queerness all year long! Many different marine species—including some found at the Seattle Aquarium—naturally display queer behavior.

Queer is a term reclaimed by some members of the LGBTQIA+ community, and it carries a long and complicated history. In this story, we take it to mean a living being who is not strictly heterosexual and/or cisgender.

Birds (and whales and dolphins) of a feather

You may have heard of Roy and Silo, a pair of male penguins at New York’s Central Park Zoo who paired up for many years and even raised a chick together. But those queer penguins are just the tip of the iceberg!

Same-sex partnerships have been documented among seabirds. In one studied group of albatrosses in Hawaiʻi, nearly a third of bonded pairs were female-female. Like male-female pairings, these birds took turns incubating a single egg while the other went off in search of food.

At the Seattle Aquarium, female tufted puffins Gil and Gertie have been bonded for over five years. During mating season, Gil and Gertie engage in billing, a flirtatious move when puffins tap on each other’s bills, and stacking, a breeding behavior where they stack several small fish in their bills. They also gather materials to build a nest together and spend a lot of time with one another.

While tufted puffins often return to the same mate, puffin “couples” like Gil and Gertie could change in the future due to new social dynamics. Just like humans, animal relationships can change.

Tufted puffins Gil (front) and Gertie (back) act as a bonded pair, spending a lot of time together and displaying flirtatious behavior at the Seattle Aquarium. Video credit: Animal Care Specialist Ana.

Dipping below the waves, many other animals also form same-sex pairs. Both male and female dolphins of multiple species—notably, bottlenose dolphins—engage in same-sex mating behavior, sometimes with multiple partners. Young male orcas split off from their pods to spend time wooing each other. Just last year, for the first time scientists directly observed humpback whales mating—and the participants were both male!

No partner? No problem!

Many marine invertebrates, from corals to jellies, can reproduce asexually, aka without a mate.

Sea stars are well known for being able to regrow a lost arm. But for some species, that detached arm can grow into a whole new individual, so long as it retained some of the original star’s central disk. One known genus, Linckia, can reproduce asexually by dropping an arm even without the central disk.

Eye-catching sea slugs known as nudibranchs often sport multiple colors on their bodies. And they sport multiple kinds of reproductive organs too! Nudibranchs have both male and female reproductive organs. They can partner up with any other member of their species and some can fertilize each other simultaneously.

Nudibranchs, like this sea lemon, who can be found at A Closer Look, have both male and female reproductive organs.

While many invertebrates can reproduce asexually, scientists consider it unusual behavior in more complex animals. But females from some species of rays and sharks, including Indo-Pacific leopard sharks, can bear offspring without any male assistance. This rare and delicate process is called parthenogenesis. It’s been well-documented among sharks and rays in human care, but more research is needed on how common it is in the wild.

Transitioning trends

As the saying goes, there’s plenty of fish in the sea. And over 500 of those species can change their sex! Some fish change sex permanently at a specific point in their lives, while others, including the blue-banded goby, can transition back and forth. One known species, the mangrove rivulus, can even self-fertilize.

Going from female to male, a process called protogyny, is the most common way fish change sex. Squarespot anthias all start out life as females and develop their namesake squarespot when some transition to male.

All squarespot anthias, a fish you can meet at the Ocean Pavilion, are born female. Some transition to male and develop the namesake purple square spot.

For clownfish, protandry, or transitioning from male to female, is the way of life. The two largest fish in a group are the reproductively mature male and female. The fish in their home anemone are all male juveniles. Should the female die, the current breeding male will transition to female and the next largest male will mature to take his place.

These are just a handful of the many species who showcase the beauty and diversity of marine life. From birds in the sky to benthic sea stars, queerness is as natural as the ocean itself.