Health care for feathered friends at the Aquarium: A birds-eye view

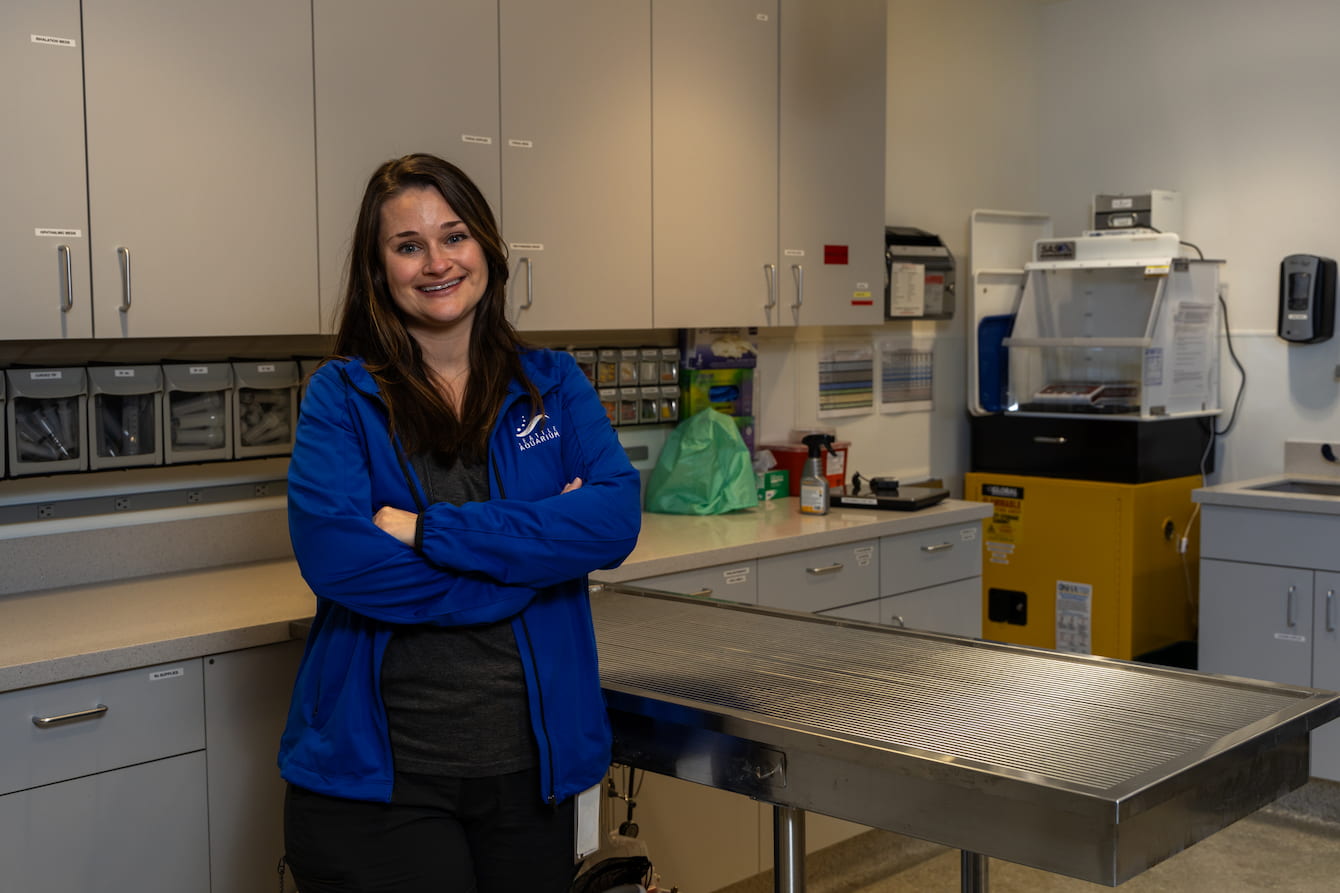

This story is part of our series, The Doctor Is In—highlighting our veterinary team’s expertise in service of animal wellbeing.

It’s not just marine mammals at the Aquarium who are trained to cooperatively participate in their own health care. The birds entrusted to us participate in their own care too. How do they do it? By eating!

“Animal care staff can closely monitor food consumption to help assess health,” says Supervisor of Birds and Mammals Sara Perry. “We count how many and what type of fish or bug each bird eats during the day. Overall behavior during a feeding can tell us a lot about the wellness of the bird as well.”

Working toward the clean plate club

When feeding alcids (including the common murres, rhinoceros auklet and tufted puffins in our care), staff can also deliver specific vitamins or necessary medications, expertly hidden in a tasty fish. It’s similar to how parents of young children may “hide” vegetables in a favorite food!

The comparison to human children doesn’t stop there: Animal care staff often need to be creative and patient when feeding birds. “They’re not like a sea otter who will usually eat anything at any time, or a seal who just gulps fish down. Ask any of our staff, feeding the birds takes finesse!” Sara laughs. “We rely on our knowledge of each bird, their behavior and their preferences—depending on time of year—and apply it to a group setting.”

"You look like you haven't aged a bit!"

Here at the Seattle Aquarium, we have a good number of elderly birds in our care. But it’s hard to know that just by looking at them. Why? Birds don’t show graying of feathers as they age, unlike the graying or lightening of hair and fur of mammals (including us humans!)—so it’s not possible to estimate age based on that indicator.

Birds do show other age-related changes that are seen in mammals, though. For instance, their mobility and vision may deteriorate over time, their appetites may change, and they may rest more than younger birds. “Our Aquarium staff know each bird as an individual, which allows us to adjust feeding and spaces to help the older ones,” comments Director of Animal Health Dr. Caitlin Hadfield. “It’s all in the name of taking the best possible care of each bird at the Aquarium for their whole lives.”

Did you know?

All the birds (and mammals) at the Seattle Aquarium fall into one of two categories—they were either born at a zoo or aquarium or they were rescued and have been deemed non-releasable according to the guidelines established by government agencies such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and policies such as the Migratory Bird Act.

Providing the very best care and quality of life for the animals entrusted to us—at all stages of their lives—is a vital part of our mission, Inspiring Conservation of Our Marine Environment. Learn more about birds at the Aquarium on our website or, better yet, plan a visit with us soon!