Remembering Dive Safety Officer Jeff Christiansen

Editor’s note: We at the Seattle Aquarium were deeply saddened to learn of the recent passing of Jeff Christiansen—an extraordinary person, lifelong diving aficionado and valued staff member here at the Aquarium for nearly 40 years before his 2021 retirement. Jeff died on August 25 after experiencing a medical emergency underwater during a night dive.

To celebrate his life and honor some of his many contributions toward advancing our conservation mission, we’re resharing a web story we published as Jeff retired from his long career with us. Our hearts are with his grieving family, friends and diving community.

Celebrating the Seattle Aquarium career of retiring Dive Safety Officer Jeff Christiansen

“You’re so lucky when you can make your passion your vocation,” says Jeff Christiansen, who retired on March 12, 2021 after a career at the Seattle Aquarium that began nearly 40 years ago. Jeff’s passion? Scuba diving. “It’s the closest you can get to another world without going into space,” he says.

Jeff’s love of diving started before he even entered elementary school in Aurora, Colorado. “I’ve been scuba crazy my whole life,” he laughs. “I learned to swim on the bottom of the pool when I was 4 years old. I grew up watching Sea Hunt and, for Halloween, I’d dress as a diver wearing a modified cat costume with oatmeal canisters on my back as oxygen tanks.”

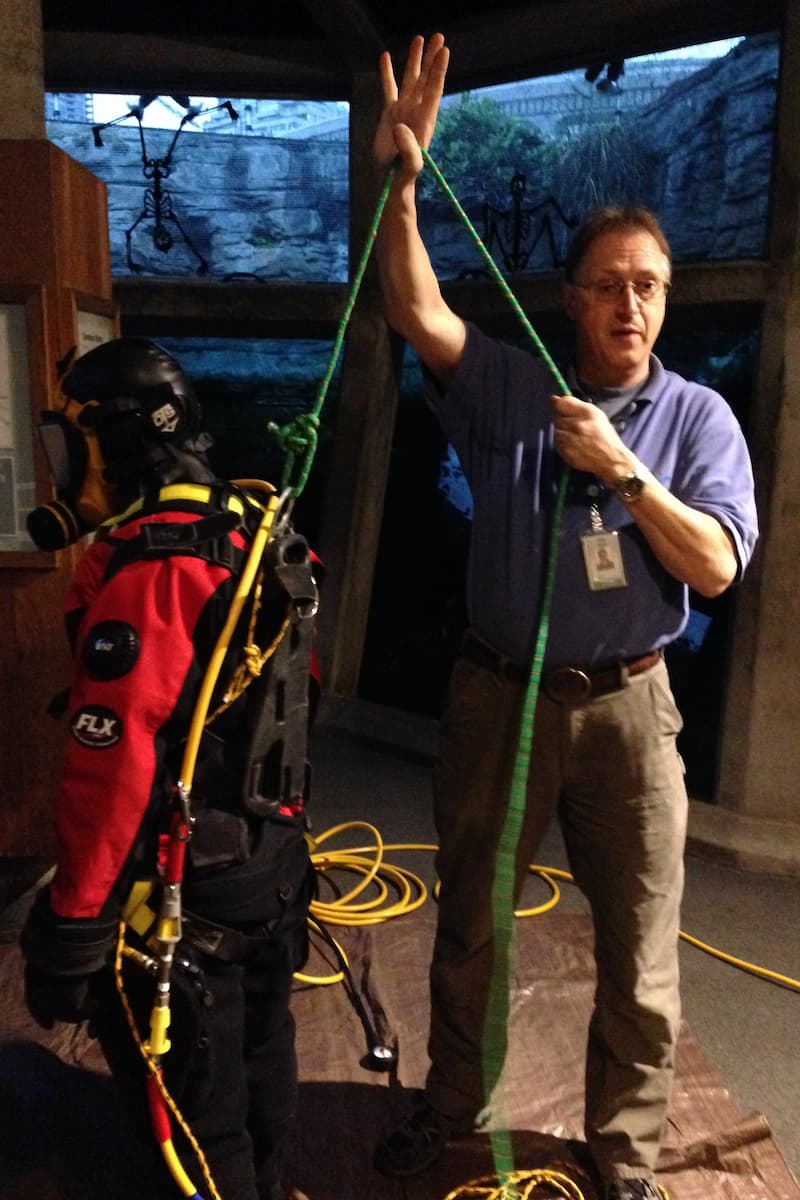

Jeff generously shared his knowledge and expertise with the Seattle Aquarium and diving communities.

When Jeff was 12, in 1968, his family moved to Seattle—and Jeff took his enthusiasm for diving to a whole new level. “My parents signed me up for scuba diving lessons, and I was certified as a junior scuba diver at age 12½,” he notes. “I helped start a scuba diving club at school. We lived on Three Tree Point near Burien, so I could walk down the block and into the water,” he adds.

As college approached, Jeff researched careers that could involve diving and landed on fisheries sciences. He became a Seattle Aquarium volunteer just a year after we opened, landing a slot in what was then called the Puget Sound Fishes exhibit in 1978. Two years later, he graduated from college and became a member of the Aquarium’s first pool of volunteer divers.

“It was a career of coming to fun, not coming to work, every day.”

Jeff joined our staff in 1982, in a role called bio guard, which was, “half life sciences and half security,” he says. His shift ran from 7pm to 3am and, despite the challenging hours, “It was a lot of fun—a very diverse position and a great way to learn where everything was at the Aquarium and how it worked,” he comments. After stints as an exhibit technician and biologist (and transitioning to working at the Aquarium during the day instead of through the night), Jeff became our assistant dive safety officer in the mid-1980s and eventually took over as the lead dive safety officer—a position he held until his retirement.

Jeff Christiansen leading a dive safety demonstration at the Seattle Aquarium.

Hearing Jeff describe highlights of his career at the Seattle Aquarium creates a quick understanding of why he describes it as “coming to fun.” He helped lead trips to Neah Bay, visiting sites that sit within Makah Tribe waters (we operate under a permit from the Tribe to enter their land/waters) and serving as the primary operator of the Aquarium’s boat. “Some of the sites we’re still visiting were found with a chart, compass and an old-school, flashing fishfinder,” he laughs. “It was a real test of our navigation skills.”

He was also closely involved in our sixgill shark research during the extraordinary era when these amazing animals were regularly spotted below the Aquarium’s pier. “Staying at the Aquarium late into the night, seeing a shark cruise by, and then having the opportunity to tag one underwater—those were some of the most exciting dives of my life,” he notes.

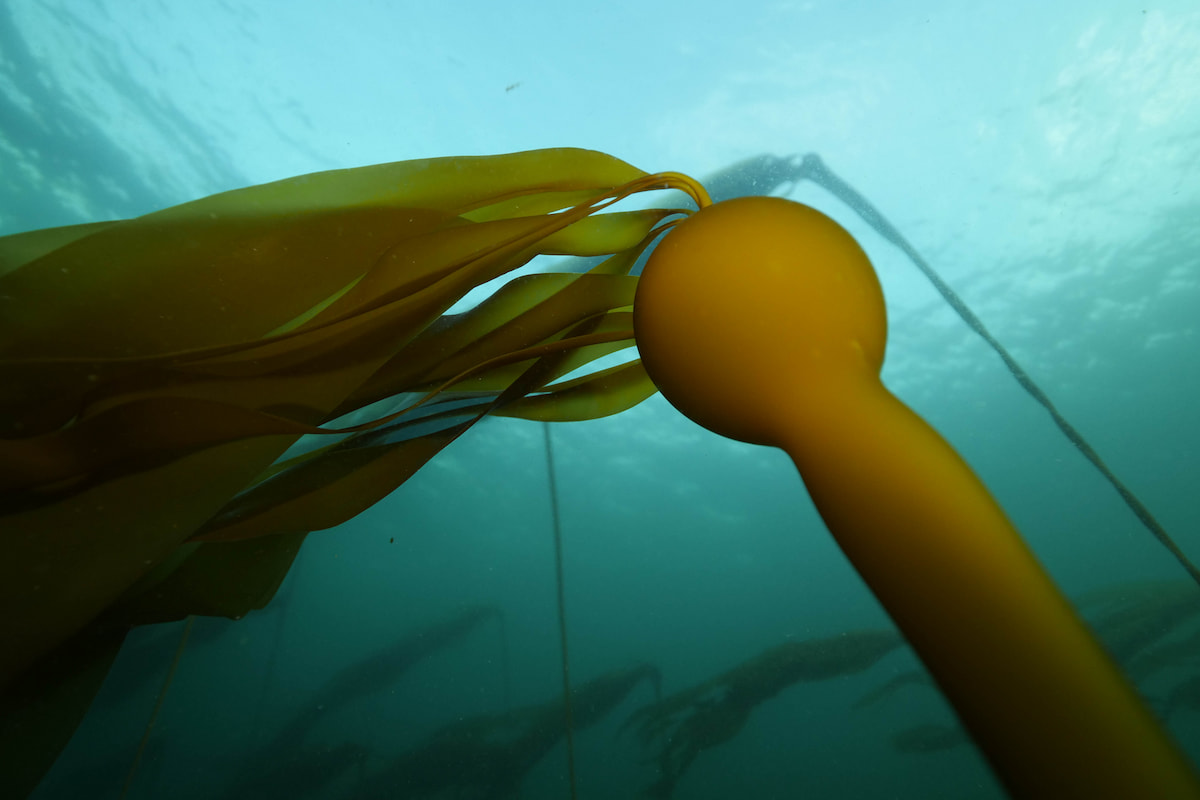

Jeff in his element, diving with underwater camera equipment.

The most fun of all? “It’s a tie between diving in the Underwater Dome and working in the Puget Sound Fish habitats before the Aquarium opens,” Jeff says decisively. “You put on the music of your choice, do your work as a professional fish janitor and get the privilege of seeing what happens as the fish wake up,” he smiles. “Watching fish for 10 minutes will solve most problems.”

“I like seeing what we’ve built.”

The Seattle Aquarium has grown and changed in many ways since those very early days when Jeff joined us as a volunteer—with many more exciting changes yet to come. “The Aquarium has only gotten better and better over the years,” he says. “It’s truly a jewel on the waterfront, doing the important job of connecting what’s going on above the water with what’s happening below the surface.”

Jeff diving off of the Big Island of Hawai‘i with then-Associate Curator of Fish & Invertebrates/Assistant Dive Safety Officer Joel Hollander, who has since become our dive program manager.

He adds, “The Aquarium is so much more than just our physical footprint. Research, conservation education, community outreach, advocacy…it’s been great to see it going in those directions and I’m looking forward to seeing what the future holds.”

From the bottom of our hearts, we thank Jeff for his remarkable years of service to the Seattle Aquarium and our mission of Inspiring Conservation of Our Marine Environment. He will be greatly missed—and we wish him all the underwater adventure he could dream of in his well-deserved retirement.