“Resharking” the ocean: Five lessons learned

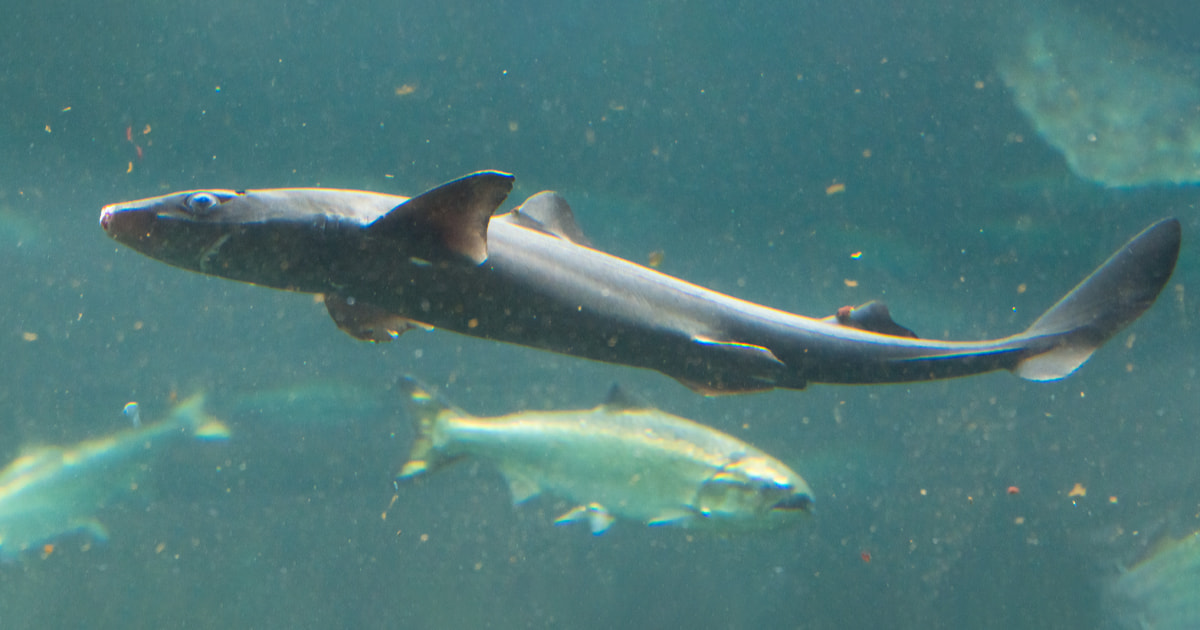

Sharks and rays are vanishing at an alarming rate due to fishing and habitat loss. When these keystone species disappear, their entire ecosystems collapse. For over two years, the Seattle Aquarium has been part of a global coalition devoted to changing the story and “resharking” the ocean.

In August 2022, the coalition—called ReShark—achieved a major milestone in its first project. Eggs laid by Indo-Pacific leopard sharks (Stegostoma tigrinum) in the SEA LiFE Sydney Aquarium were moved from Australia to a new shark nursery in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. Pups have already hatched and are growing quickly! When they’re mature, they’ll be released into their home waters to help bring back their species locally and safely within marine protected areas. And ReShark’s work will continue, with new eggs, new locations and new species to recover.

Dr. Erin Meyer, Director of Conservation Programs & Partnerships at the Seattle Aquarium, has helped build the coalition from its earliest days and chairs the project’s Steering Committee. She shared five key lessons from the first chapter of its work.

1. Aquariums can help bring back endangered marine species.

Aquariums have been advocating to protect ocean health, mobilizing communities and educating people about endangered marine animals. We can also help reverse the exponentially increasing number of species listed as endangered or critically endangered. For some endangered species, protecting and restoring habitat areas isn’t sufficient. Because if their numbers get too low, they can’t successfully reproduce. And that’s where aquariums can step in because we are the organizations with the expertise and experience in breeding, rearing, feeding and caring for these animals in ways that no other organization can do. It’s an incredible opportunity to put our knowledge to work to restore threatened species in the ocean.

How ReShark Works

- Sharks and rays living in accredited aquariums lay eggs (or, depending on the species, pups).

- Eggs or pups are transferred to special nurseries built by local communities in areas where species are in decline and other protective measures have not brought back their numbers.

- At the nurseries, trained local aquarists rear shark and ray pups.

- Once ready, juvenile sharks and rays are tagged and released into their home waters.

2. Building global partnerships takes time.

The first time I heard the idea for what would become ReShark was in early 2018, about a month after I got the job at the Aquarium. I then became part of a small group of colleagues from around the world that kept talking about the possibility over the next two years. Could we do it? If we did, how would it work? We formally launched the first project in February 2020. Then the pandemic began. Still, we kept going, working virtually with local leaders in Indonesia to get permits, building a nursery for baby sharks at the Raja Ampat Research & Conservation Centre, training aquarists in Indonesia, finding viable eggs to ship. Moving our first set of eggs in August took a huge amount of work behind the scenes by so many people. (See all ReShark partners involved in this work.) In August, I got to see the nursery for the first time in person—this amazing structure we’d all been working toward for two years. For me, that’s when it became very real.

ReShark by the Numbers

70+ partners | 13 countries | 2.5 years of planning

3. Cross-cultural collaboration moves at the speed of trust.

Conservation is about people. And we are agents of change, both damaging and regenerative. Collaborative conservation is intentional, co-led and begins with a blank slate. ReShark’s first project is co-designed and co-implemented with the West Papuan government in Indonesia as critical partners in this coalition. It would not have been possible without local leadership. Doing cross-cultural conservation work in a way that centers the priorities and needs of the people in the country where the work is taking place is incredibly important for this project and for the future of conservation in general. I often hear in the environmental justice community that work like this moves “at the speed of trust.” It takes years to earn trust and seconds to break it. As ReShark grows to include more species and more locations, we will continue to center the perspectives and expertise of local partners, breaking the colonialist approach to conservation, challenging our biases and checking our privilege. Conservation requires leaning into uncomfortable spaces, and we’re not shying away from that.

4. Restoring species means being willing to learn and adapt.

I’m not a shark biologist; my expertise is in invertebrates, ecosystems and conservation action. I’ve learned that it’s a far harder thing to move eggs around than I ever thought it would be. It seems so simple! You get the right animals, the right habitat, they make eggs and then you move the eggs, right? Wrong. It’s incredibly complicated. Bringing people to the table with unique experience and expertise is how this project has gone as far as it has. And we will continue to bring new perspectives and new expertise to the table as we grow. So far, we’ve successfully moved eggs and seen pups hatch. These are huge milestones! And now we’re hopeful that the animals will thrive, that we’ll be tagging and releasing them in the coming months. But we don’t yet know the outcome of this work because nobody’s ever done this before.

5. Hope is the key.

When the Seattle Aquarium’s Ocean Pavilion opens in 2024, we will have the opportunity through that platform to show people these incredible animals that exist on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. We’ll also have a new platform to talk about this initiative to bring sharks and rays back from the brink of extinction: to not only tell people that there are almost 400 species of sharks and rays listed as endangered or critically endangered around the world, but also, here’s what we—all 70+ partners—are doing to turn that back around. I believe that will bring a sense of hope to people who visit.

And importantly, our visitors can take action in their daily lives to help sharks and rays throughout our one world ocean. We’re all connected.