From youth engagement to ocean policy advocacy, the Seattle Aquarium is working to advance climate solutions to avert further ocean acidification and ocean warming and build the resilience of marine ecosystems and coastal communities. Climate change is a multifaceted challenge, with impacts at local, state, national and global scales.

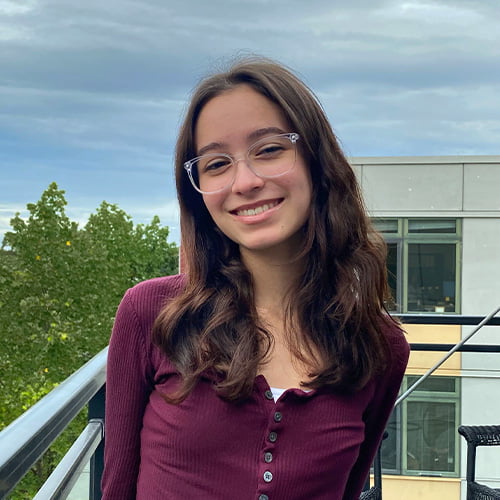

Here, Interpretation Coordinator Nicole Killebrew and Senior Ocean Policy Manager Nora Nickum discuss the challenges of climate change, potential policy solutions and opportunities for hope.

Can you describe some of the ways climate change harms ocean animals and our marine environment?

Nicole: Climate change is caused by burning fossil fuels like coal, oil and natural gas. When we burn fossil fuels in excess, that creates a heat-trapping blanket around the Earth, warming the ocean and land. This fuels extreme weather events, alters where animals can live and travel, shifts food availability, and changes the chemistry of the ocean through a process called ocean acidification. The ocean is like our planet’s heart, and just like a heart circulates blood and regulates the body’s temperature, so does the ocean for our planet by circulating heat, moisture and nutrients. Burning fossil fuels puts stress on our ocean and damages the ocean’s ability to keep the climate stable. These climate impacts increase survival stressors on marine animals around the world in a number of ways. Climate change also puts strain on the resilience of marine ecosystems that animals rely on as their home.

Nicole, how has your work as an educator informed the way you speak about climate issues?

Nicole: I’m involved with the National Network for Ocean and Climate Change Interpretation. That work focuses on identifying the core story of climate change and telling that story so that people feel hopeful and empowered to take action. We need to connect people based on their values and things they already care about to collectively work toward solutions. We also need to keep social and environmental justice in mind—there are differences in how different communities are affected by ocean disruptions and climate change. It comes down to raising our voices and rethinking our reliance on fossil fuels as a primary energy source.

Nora, how can policy solutions help build climate resilience across the United States and the world?

Nora: Taking action to reduce emissions and build resilience is urgent to avoid worsening impacts on human communities and ecosystems. We can all make changes in our daily lives to help with that, like taking public transportation instead of driving. But we also need big changes to happen quickly and at scale. That’s where policy plays a key role.

What types of national climate policies does the Seattle Aquarium support and why?

Nora: We’ll need multiple policy solutions to address climate change—but fortunately, there are a lot of good, science-based ideas out there. There are currently several bills in Congress that the Aquarium is supporting. The Blue Carbon Protection Act (H.R. 3906), for example, would mobilize new funding to protect and restore blue carbon ecosystems—like mangroves, tidal marshes and seagrass beds—and increase long-term carbon storage. The Ocean-Based Climate Solutions Act (H.R. 3764) would prohibit the expansion of offshore oil exploration and drilling on most of the Outer Continental Shelf; promote decreases in shipping emissions; and create a grant program to support climate research and resilience with Indigenous and local knowledge. And the Climate Resilience Workforce Act (H.R. 6492) would ensure there’s a skilled and equitable workforce capable of preparing for and responding to climate change. We also support carbon pricing policies that are science-based and center the voices and needs of those disproportionately impacted by pollution, and we advocate for phasing out fossil fuels as rapidly as possible.

I also want to mention the importance of policies to reduce single-use plastics. Plastic is largely made from petroleum and there are greenhouse gas emissions at every stage of the production process. Reducing single-use plastics will also have the benefit of reducing pollution along shorelines and in the ocean.

There are more policies needed, but these are all meaningful steps in the right direction.

What is a story of hope that has resonated with you?

Nicole: One very tangible example was the Seattle Aquarium’s participation in the Community Solar Program. Through the program, community members could purchase solar panels to put on our roof. They receive credits for renewable energy and the power is part of the Aquarium’s general power grid. The program not only supports renewable energy, but also has an additional psychological benefit: What kind of message does it send to the community to look at the roof of the Seattle Aquarium and see it covered with solar panels?

Nora: I find hope in the many ways we can reduce emissions, build climate resilience and protect biodiversity all at the same time. There are so many good ideas and “shovel-ready” projects out there, we just need to prioritize and invest in them. For example, eelgrass beds can store huge amounts of carbon—keeping it from entering our atmosphere as carbon dioxide. They also protect coastlines during storms. And they provide important habitat for forage fish and juvenile salmon. We can realize all of these benefits by protecting and restoring eelgrass beds. This legislative session, we supported a bill in Washington state to ensure the Department of Natural Resources now has the resources to create a collaborative plan to restore or conserve 10,000 acres of eelgrass meadows and kelp forests by 2040.

Do you have advice for someone interested in raising their voice for ocean-climate action?

Nora: Contact your members of Congress to let them know you want to see urgent action on climate change. You could ask them to support any of the specific policies I mentioned earlier. Most importantly, tell them why you care about the climate crisis, which will make your message personal and memorable.

Nicole: There are many ways you can support renewables, including through community solar programs or rounding up your energy bill to have funds go directly toward renewable energy. Puget Sound Energy and Seattle City Light provide that option, and you could ask your energy company to if they don’t already. Beyond renewables, ask questions and reach out to organizations focused on climate action. See how you can get involved!

What do you hope these solutions can achieve in 10 years? Fifty years?

Nicole: It comes back to the core mechanism of why climate change is occurring—we need to shift away from fossil fuels toward a renewable energy system. Reducing our fossil fuel use is a step in that direction. If we can do that, we’ll see a stabilization in the climate system, ensuring the ocean can continue to function in a way that supports marine life and communities around the world. My hope is that people feel empowered to take action and feel connected to our climate system. Together, we can work toward positive change.

Nora: I envision us on a new path where all communities and ecosystems can be resilient and thrive. We can get there if we speak up, prioritize action and investments today, and see not just the problems we need to fix, but all the benefits we can achieve for people, public health, biodiversity, access to nature and more.