The doctors (and techs) are in: Getting to know the Seattle Aquarium’s veterinary care team

This story is part of our series, The Doctor Is In—highlighting our veterinary team’s expertise in service of animal wellbeing.

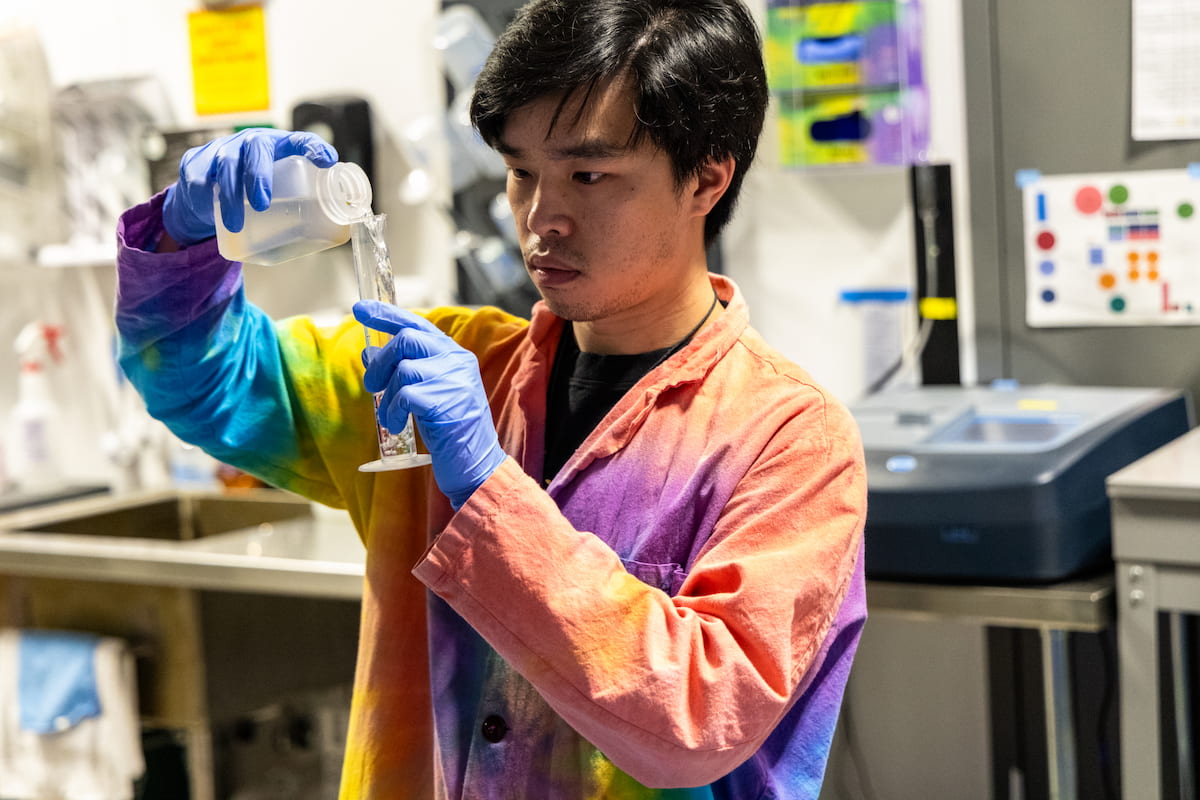

Providing medical care for the animals at the Seattle Aquarium—soon to be nearly 18,000 with the opening of the Ocean Pavilion!—is far from a one-person endeavor. Working to provide excellent animal health and wellbeing requires skill and expertise from a well-rounded veterinary team, one that is required to be available any time of the day or night, every day of the year.

The Seattle Aquarium’s veterinary care team is currently composed of six people:

- Two full-time veterinarians—Our director of animal health and team leader, Dr. Caitlin Hadfield, MA VetMB MRCVS DiplAZCM DiplECZM and Dr. Sasha Troiano, DVM MS CertAqV;

- Two relief veterinarians, who are available to step in when our staff veterinarians are unavailable and/or extra support is needed—Dr. Brian Joseph, DVM MFAS CertAqV and Dr. Alicia McLaughlin, DVM CertAqV; and

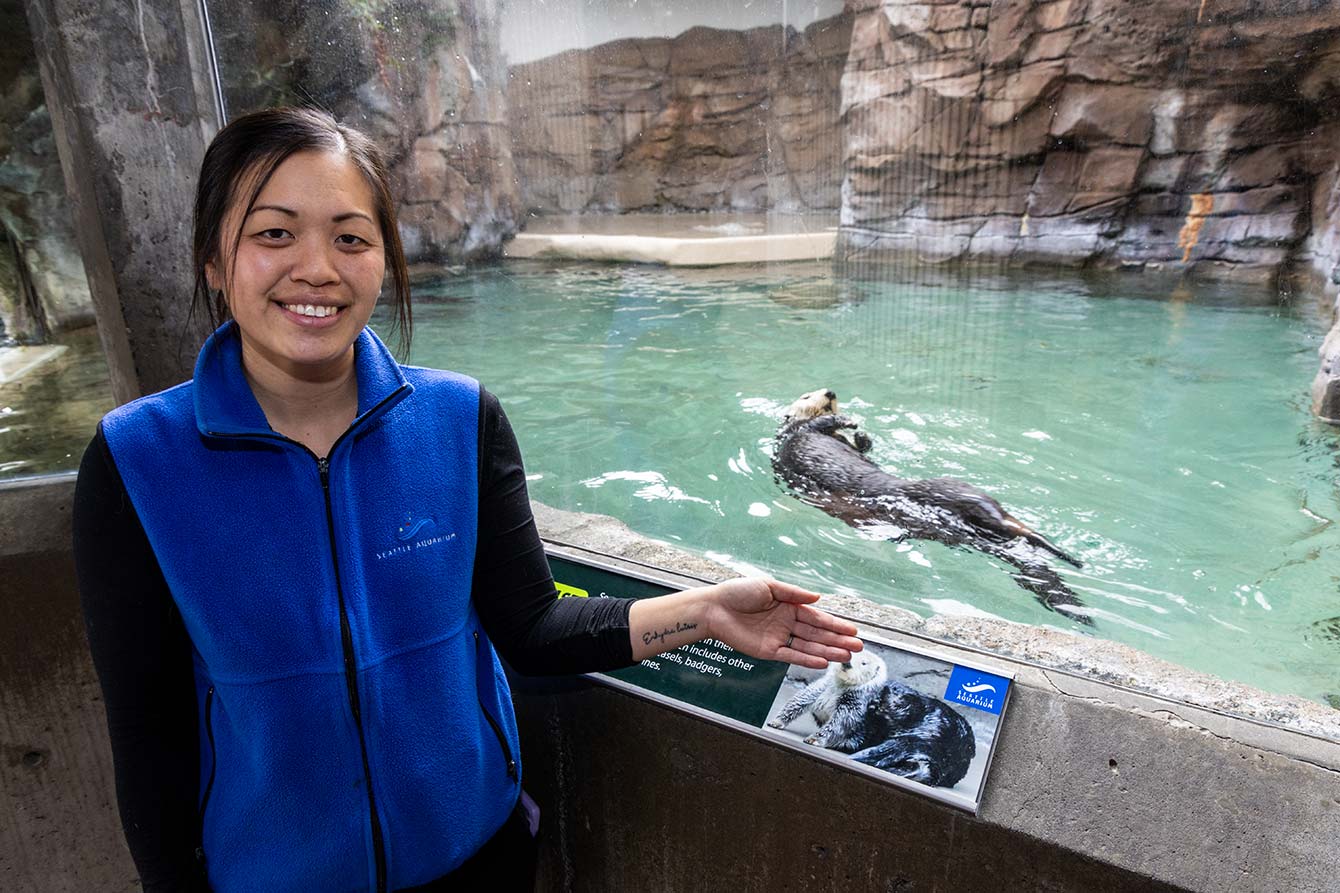

- Two veterinary technicians*—Lindy McMorran, BS LVT Cert AqVN/T and Erika Russ Paz, BS LVT.

*Not sure what a veterinary technician is? Be on the lookout for our upcoming web story, in which we’ll introduce you to Lindy and Erika and share some highlights of what they do—as well as details about a prestigious new credential that Lindy recently earned!

Initials = hard-earned credentials

Did you happen to take in the initials following our vet team’s names? They’re credentials—each one representing extensive education and certification.

For instance, staff vet Dr. Sasha Troiano and relief vets Dr. Brian Joseph and Alicia McLaughlin have doctorates of veterinary medicine, or DVMs. The three also have certified aquatic veterinarian (CertAqV) credentials from the World Aquatic Veterinary Medicine Association (WAVMA), indicating their extensive experience working with aquatic animals. In addition, Dr. Troiano has a Master of Science (MS) degree; Dr. Joseph has a Masters of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (MFAS) degree.

Lindy McMorran and Erika Russ Paz have Bachelor of Science (BS) degrees—marine biology for Lindy; marine science with a minor in biology for Erika—and licensed veterinary technician (LVT) credentials. In addition, Lindy recently received a certified aquatic veterinary nurse/technician (CertAqVN/T) credential from WAVMA—more on that in our upcoming web story!

As for Dr. Hadfield’s credentials, we’ll let her explain them in her own words:

- MA: “I did a bachelor’s degree in zoology that included a master’s.”

- VetMB: “Then I did my vet degree, which goes by those initials at University of Cambridge —the initials vary a bit by school.”

- MRCVS: “That means I’m in good standing as a member of the United Kingdom’s Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. It’s an odd requirement from England!”

- DiplACZM: “These letters are for board certification. This was my first one, with the American College of Zoological Medicine—that’s what the ‘ACZM’ is for. Qualifying to take the exam requires years of clinical experience and publications. That’s followed by a challenging exam—in my case, I specialized in aquatics for my second day of exams, while day one had everything from red-eyed tree frogs to rhinos.”

- DiplECZM: “I was also able to get certified with the European College of Zoological Medicine—the ‘ECZM’ in the title—and become a ‘diplomate’ of that group.”

Benefitting animal wellbeing beyond the Aquarium's walls

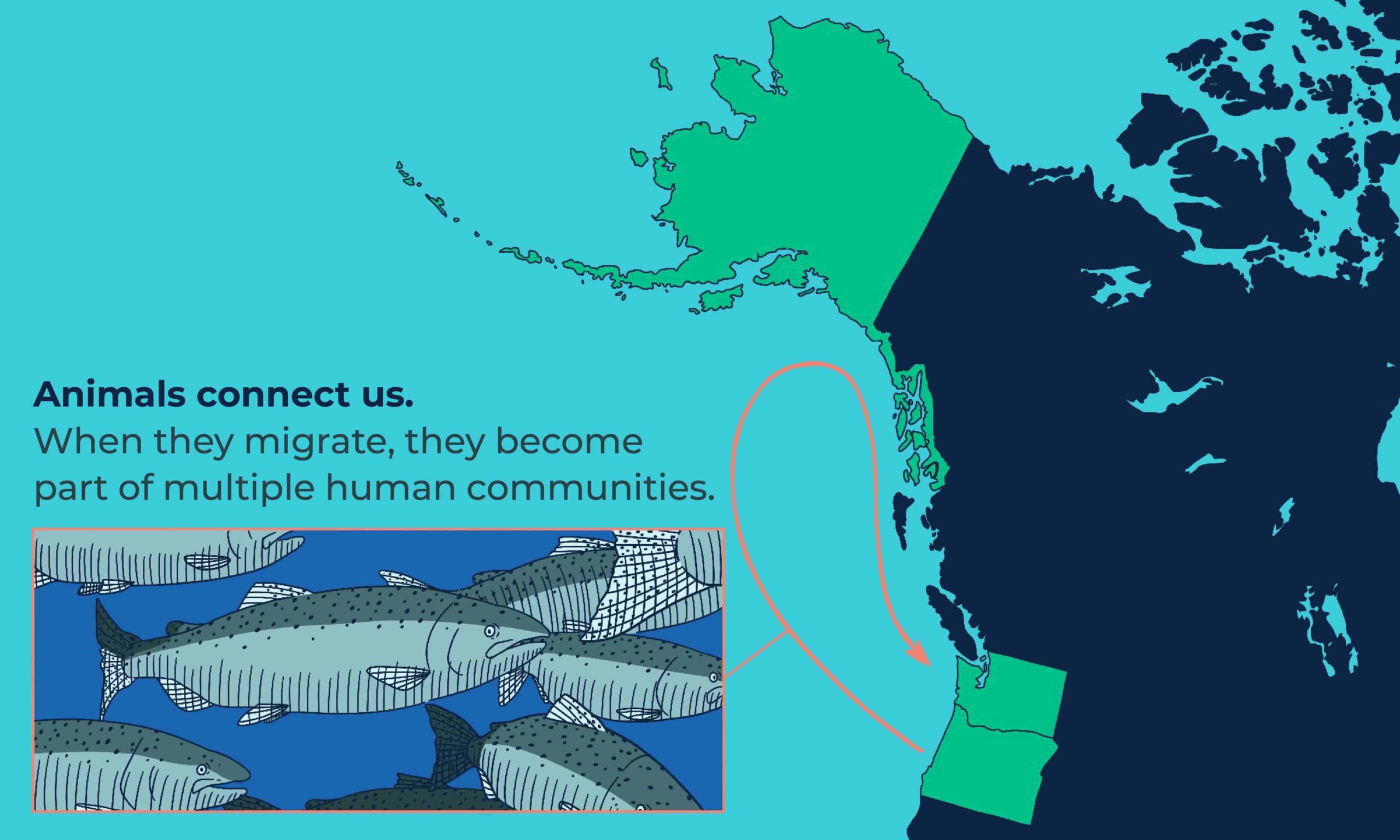

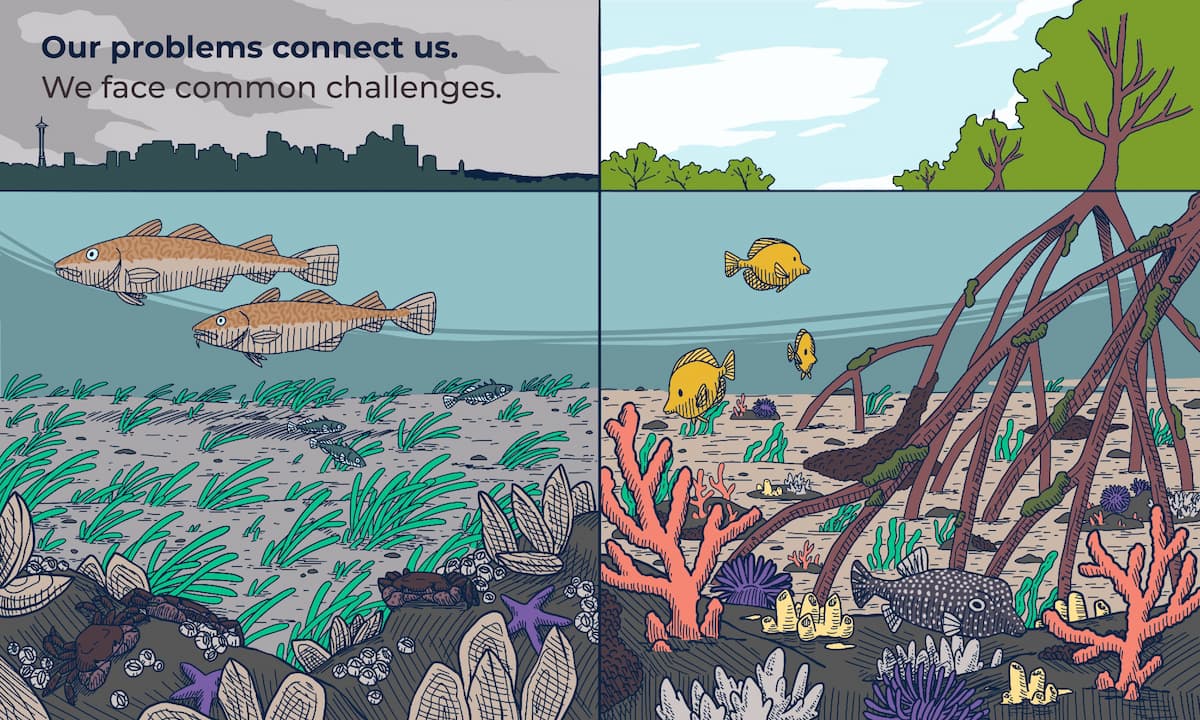

Members of the Aquarium’s veterinary, water quality and animal care teams share their expertise with the larger community in many ways—for instance, serving in leadership roles with the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (a nonprofit, independent organization that accredits zoos and aquariums, including the Seattle Aquarium, worldwide); helping to rescue and rehabilitate stranded animals; participating in research on wild populations; making presentations; collaborating on and authoring papers and articles—and even co-authoring an entire textbook on fish medicine.

That’s right: On top of her regular duties, Dr. Caitlin Hadfield found time to co-author the 624-page Clinical Guide to Fish Medicine. Written for vets, vet techs, biologists and fish enthusiasts, it’s now required reading for zoological board exams.

What kind of exams are those? “Just like your dentist and knee surgeon have done additional exams to confirm their specialization, there are boards for vets who specialize in zoological medicine or specific types of animals,” Dr. Hadfield explains. “Boards require a lot of extra studying and difficult exams. It’s great to be on the required reading list because it ensures a steady stream of readers! But more importantly, it helps set high standards for health care of fish.”

The book was the first of its kind. “There are textbooks that provide practical information on clinical medicine of domestic species—like dogs and cats—that vets can refer to through the day while at work, but that resource just didn’t exist for fish,” notes Dr. Hadfield. “There are good textbooks on fish, but they are focused on specific aspects of fish medicine or particular diseases and aren’t as useful in a busy clinical setting. So we submitted a proposal to the publisher and they accepted.”

A true team effort

For any team to be successful, each member must bring something different and valuable to the table—and that’s definitely the case at the Seattle Aquarium. “I’m really proud of the team’s diverse skills and how we work together and learn from each other,” comments Dr. Hadfield. “We provide care whenever it’s needed: any time of day or night, any day of the year,” she adds, “so we need a team that can be one voice for animal care and wellbeing, and support the wellbeing of the staff and volunteers we work with. That’s a big task given the variety of species in our care.”

And that variety is increasing in a big way with the opening of the Ocean Pavilion this summer. Interested in a behind-the-scenes look at some of the species you’ll find there—and a chance to see Dr. Hadfield and other Seattle Aquarium team members in action? Check out episode six of our Animal Care Stories series. And if you’re curious about what it takes to become an aquarium vet, dive into this great conversation with Dr. Hadfield!