Taking a bite out of food waste: Composting supports sustainability at the Seattle Aquarium Café

Compostable packaging from the café ends up helping local farmers grow lettuce and other produce—which then gets served at the café! Photo credit: Sound Sustainable Farms.

When you sit down to enjoy a delicious lunch in the Seattle Aquarium Café, there’s a chance that the lettuce on your burger was grown using “trash” from the Aquarium.

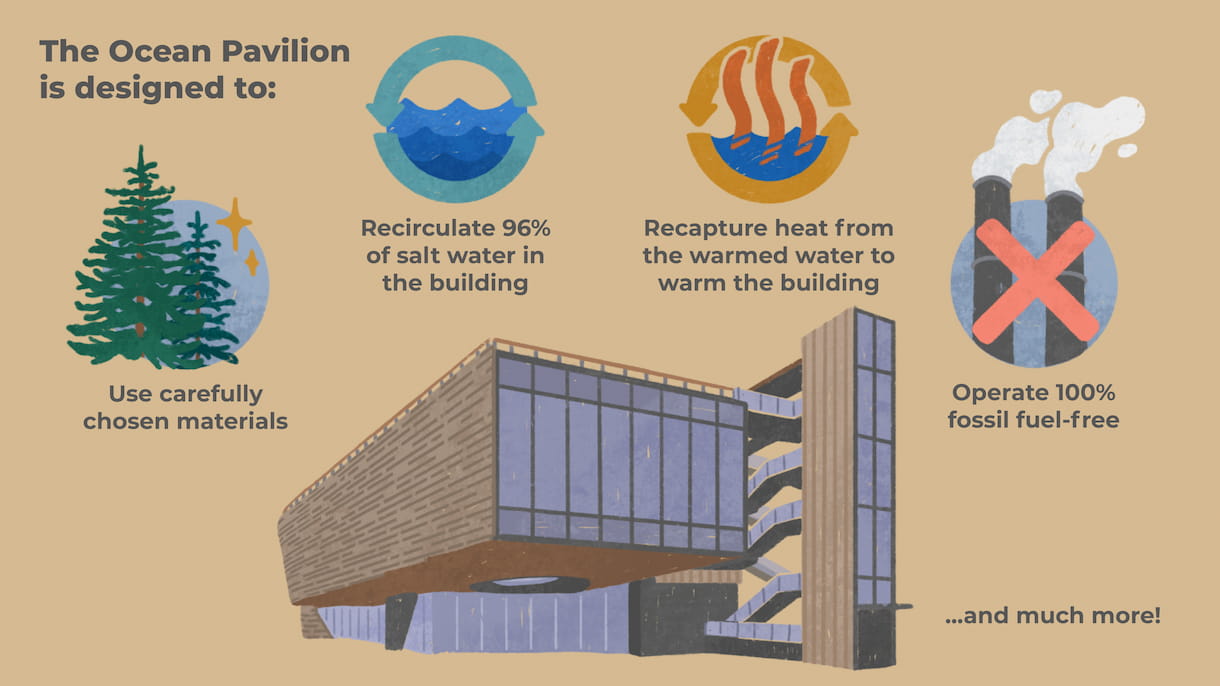

As a part of our vision to become a regenerative institution—one that gives back to the environment more than we take from it—the Aquarium has a complex relationship with “trash.” We know it well. That’s because we work to divert as much “trash” as we can from landfills, with the ultimate goal of becoming a zero-waste facility. Instead, most items on our campus can be recycled or composted.

Composting is a method of breaking down or “recycling” organic matter, including food scraps, into a rich material that resembles soil. Growers use the finished compost to enrich their soils.

OVG Hospitality, which operates the Seattle Aquarium Café, partners with the local composting company Cedar Grove. Cedar Grove provides the compostable packaging for café food and handles the composting process afterward.

Finished compost like this is a soil enricher made of broken down organic matter.

When a used compostable fork or cup enters the compost bin at the café, that is just the start of its journey. Cedar Grove picks up the Aquarium’s compostable materials, which also includes other organic waste and paper towels, and takes them to their composting facility. There, it is processed and refined into high-quality compost.

After that, the compost gets put to work at Sound Sustainable Farms, an organic farm in Redmond that is also operated by Cedar Grove, where it enriches the soil for local produce, which can be enjoyed by many businesses and community members.

Available produce at Sound Sustainable Farms varies by season, but the Aquarium mainly purchases leafy greens like lettuce and kale. We strive to source as much produce as possible from them and plan to buy even more as they continue to scale up their operations.

Cedar Grove’s rich compost is also used by other organizations, including the City of Seattle, and can be purchased by anyone. That means the Aquarium’s food waste goes on to support gardens, farms and green spaces across the region. Through the composting process, the Aquarium and our community can participate in “closing the loop” on sustainability, where discarded “waste” can actually be processed and used in a way that allows for future growth.

By composting food scraps, yard waste and other organic matter, Cedar Grove diverts hundreds of thousands of tons of waste from landfills every year.

The Seattle Aquarium Café also recently took another exciting step toward sustainability by swapping out gas-powered food prep equipment for electric appliances earlier this year.

We all have a part to play in caring for the environment, including by making more conscious decisions about the ways we choose, prep, store and dispose of our food and other waste. So, the next time you’re at the Seattle Aquarium, double check before tossing something out. We’ve got some handy signs in the café to help you sort your “trash.” Because that napkin or spoon could have a second life nourishing somebody’s lunch.