Marine ink-spiration: Tattoos of the Seattle Aquarium, part 2

A few weeks ago, we introduced you to some of the many Seattle Aquarium team members who are so passionate about the marine environment that they’ve gotten tattoos representing the animals nearest and dearest to their hearts.

Now we’re back with our second installment—featuring a group of five outstanding individuals who met with us to share their tattoos and the inspiration behind them. We hope you enjoy getting to know these folks and reading the stories behind their ink!

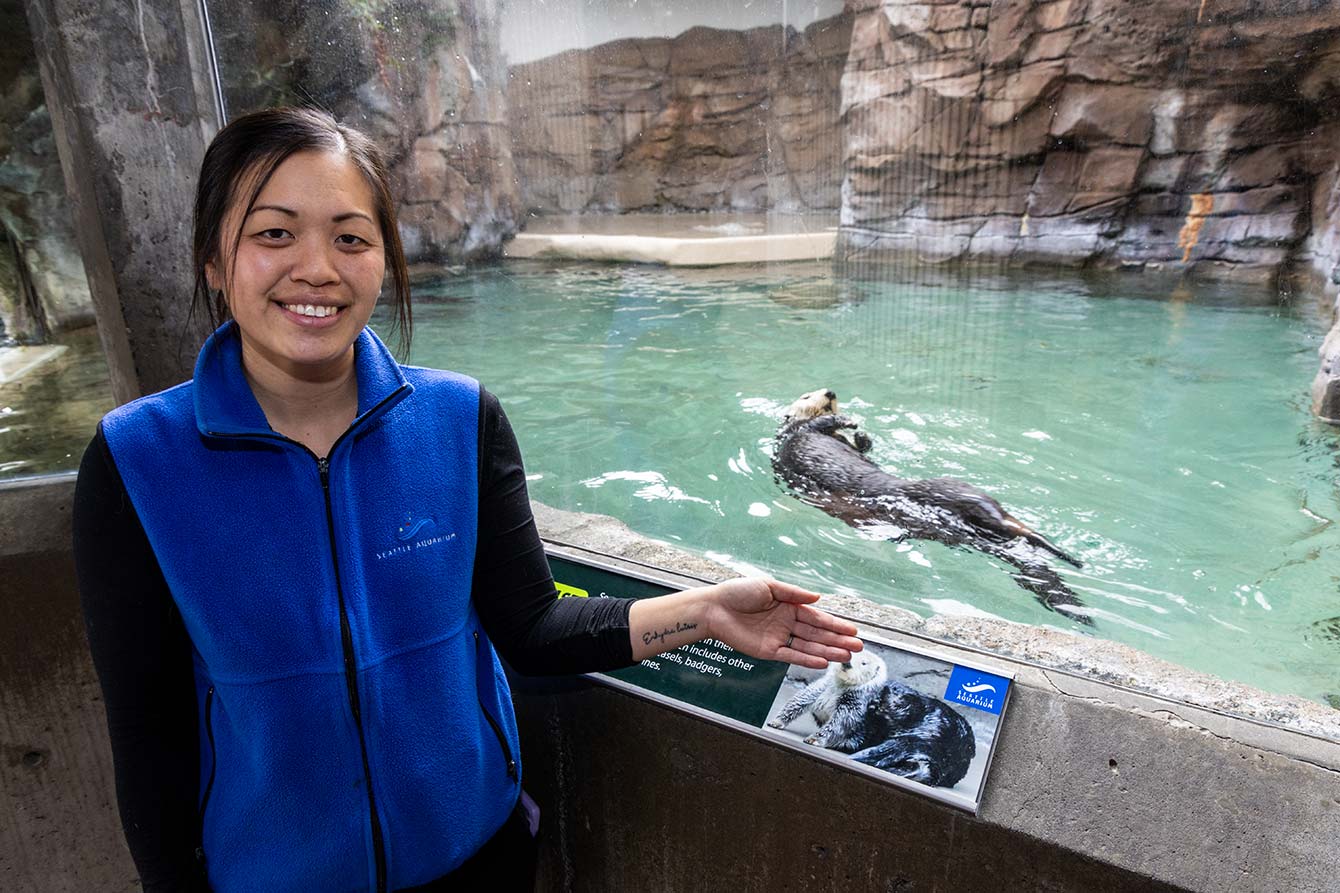

“My tattoo is the scientific name for sea otters: Enhydra lutris. They got me into this field of work that I love, and I wouldn't want to be doing anything else.”

—Kelli Lee (she/her), animal care specialist

“This is going to sound silly but, growing up, I enjoyed watching a show called The OC. In the last season, my favorite character started advocating for southern sea otters, which are found along the California coast.

I grew up in the Bay Area, more inland, so I didn’t have much exposure to marine mammals. When I first saw the show, I didn’t know exactly what a sea otter was. Obviously, I thought they were really cute—and then I started looking into them, how they’re a keystone species and how living so close to civilization has created challenges for them.

I pursued my first internship, at Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium, because it was with sea otters. I wanted to get experience with them to see if I wanted to work with terrestrial or marine animals.

I loved them right away. But it was working with other species in that section of the zoo, like harbor seals and puffins, that made me really want to stay with this. So l have sea otters to thank for me getting into the aquarium field and specifically focusing on marine animals.

My favorite is training with the animals, especially new behaviors. You have to be thoughtful of what species you’re working with and the individual, because everybody is different, with their own ways and speeds of learning. It’s really cool.

Working with my team is also something that I really enjoy. We help each other through the ups and downs of work and our lives too. It’s great to have support like that at work.”

—Kelli Lee (she/her), animal care specialist

Tattoo by Kendal Tull-Esterbrook at Lilith Tattoo, Instagram @lub.dub.tattoo

“A cuttlefish felt right: I had a job that I enjoyed in an organization that I appreciated during an important transition in my life. It all came together at the same time.”

—Jessica Williams (she/her), philanthropy data entry specialist

“I’ve always loved cephalopods. Anything in that group—I love it if it’s free-flowing and tentacle-y. I think they’re so graceful and magical. Especially cuttlefish. I love how they look like spaceships, the way they hover at a very specific angle. I can’t get enough of them.

I moved to Seattle looking for a clean slate. You may notice that my tattoo has the colors of the transgender flag. I moved here because I’m trans and this is a wonderful place to transition. I have family up here. Everything came together: Seattle was the place for me to go next.

I was floating, not sure what I wanted to do, but I knew the kind of mission I wanted to serve, the kind of place and people I wanted to be around. For me, that’s the Seattle Aquarium. I love my team. It’s such a good group and I’m happy to work with people I’m so frequently in awe of.

I like that the Aquarium is trying to change the conversation around animals that people don’t necessarily have a lot of empathy for. I love the concept of not lower intelligence, but different intelligence—and that we have the opportunity to widen people’s idea of what animal intelligence is.

I also think the Aquarium is elevating the conversation that a lot of people living next to a body of water are having: ‘This is valuable. We need to save it.’ It’s not just us working here who care—there’s a community of people around us who want to see this place succeed and help the marine environment thrive.”

—Jessica Williams (she/her), philanthropy data entry specialist

Tattoo by Grace Peters at Grace Does Tattoos, Instagram @gracedoestattoos

“It reignited that passion in me: ‘Here’s an opportunity where I can actually make a difference and see that difference in the world.’ ”

—Emma Leiser (she/they), web intern

“I got my kelp tattoo because I’ve always felt strongly about our ocean and environment and wanted a little something on my body to represent that. I love that kelp is such a vital part of so many different ecosystems. It’s shelter, it’s food…it’s a beautiful resource for so many different creatures, and I just think that’s super neat.

I was a very science-driven kid. In high school, I took a marine biology class, which was really cool because I was at a small, rural, poor school—we didn’t even have a physics class. But we had an amazing teacher with a degree in marine ecology. She had a full roster but was so passionate that she wanted to teach marine biology too. That was an incredible experience for me as a young kid in inland California, three hours from the coast.

Growing up, we never really went on vacations but we did go tide pooling occasionally, and that was—oh my gosh, so magical. That’s why I love that the Aquarium has programs like the Beach Naturalist program. Just giving kids and families opportunities to explore what’s in their local environment. It’s one thing to read and learn about it, and it’s entirely different to actually experience it and make that connection with your local waters and all the creatures living there.

I saw the opening here at the Aquarium and got so excited because I love the work that’s being done here—and I didn’t even know about half of it yet. I just really desperately wanted to work somewhere that was actually fighting to make a difference.”

—Emma Leiser (she/they), web intern

Tattoo by Callie Little at Good Habits Tattoo, Instagram @goshcallie

“I've always had a passion for marine life, but didn't always have a lot of opportunities to experience it, growing up in Minnesota. Little bits of my history and my love of animals carried me to the point of wanting to get a beluga whale tattoo.”

—Ben Swenson-Klatt (they/them), annual fund officer

“I have a particular affinity for beluga whales, which goes all the way back to my early childhood. My parents would read the book Baby Beluga to me and I had the joy of getting to see them at the Shedd Aquarium when I was young. My parents like to joke that I broke down in tears because I was so excited to see them. I’ve always just loved them so much.

I have a tattoo artist friend and pitched the idea of a beluga whale wearing a hat. My fun story is that I had already booked the appointment when I was in the process of interviewing, and I got the tattoo on the day that the Aquarium offered me the annual fund officer job. It definitely felt like a wonderful coincidence.

I fully believe that there is no action too small to take to protect our environment and, obviously, things like recycling make a big difference. But putting your money where it matters, I think, is a really important thing. Even something small really can make a big difference.

I look at fundraising as a way to organize collective care around things that are important to a community. And, for me particularly, I think that something that’s really inspiring about the Aquarium is that there’s this care in the Seattle community for our environment. We’re blessed to live so close to these incredible natural features. Having an organization that’s on Puget Sound and taking care of it—I think that’s a really important thing for the city to believe in.”

—Ben Swenson-Klatt (they/them), annual fund officer

Tattoo by Gabby Clarke, Instagram @_honeydewd_

“Sunfish are such cool, unique animals. I think it's inspiring that they start as itty-bitty plankton and grow into the heaviest bony fish in the ocean.”

—Kaitlin Brawley (she/her), aquarist

“The reason I get tattoos is mostly to mark new chapters in my life and commemorate things that are important to me. In some cases they celebrate new jobs, places and experiences; others helped me find closure from loss or big life transitions. Whatever the reason, they always end up being very special to me.

The sunfish was one I had wanted for a while. To me, sunfish represent big things growing from small things. And they truly embody the ‘just keep swimming’ mentality, so they’re special to me in that way. I moved around a lot as a kid because my dad was military, so I’ve done a lot of starting small and just swimming until I get things figured out. Bigger things come from that.

I wasn’t diagnosed with ADHD until I was 20. So I had a learning disability that impacted my grades and ability to study, to the point where I almost had to drop out of college. Then, after I got diagnosed and figured some things out, I got my life rolling on a better track. I ended up doing an internship with Monterey Bay Aquarium and moved to Hawai‘i to pursue diving and then, finally, the job here.

I think aquariums play an important role in connecting people to nature and getting them to care about it. Being part of that mission is something I really appreciate. Anytime I talk to someone and they say, ‘Oh, we love going to the Seattle Aquarium,’ it makes me happy to be part of that.”

—Kaitlin Brawley (she/her), aquarist

Tattoo by Anthony Bending at Lady Luck Tattoo, Instagram @ladylucktattoohawaii

Interested in joining the people featured in our web story with a job at the Seattle Aquarium? No tattoos required! Visit our careers page to see our latest open roles.