Students at Muckleshoot Tribal School name new octopus

One of the Seattle Aquarium’s newest residents weighs 20.5 pounds, sports eight arms and hails from the chilly waters of Neah Bay. She’s already helping visitors understand the importance of her species—the giant Pacific octopus—to local ecosystems.

The young octopus also has a special name—sqiqələč (skee-sku-luch)—that reflects the Aquarium’s place on traditional and contemporary Coast Salish land. sqiqələč means “baby octopus” in the Lushootseed language. The name was chosen by middle- and high-school students in a language and performing arts class at Muckleshoot Tribal School.

The Salish Sea is rich not only in biodiversity, but also in linguistic diversity. The language of the land and headwaters where the Aquarium resides is Lushootseed. As noted on the Muckleshoot Tribe’s website, “The Lushootseed language was nearly lost through the forced assimilation of the boarding school era beginning in the early 1890s. Today, Muckleshoot, as well as many other Coast Salish Tribes, are working to restore and preserve Lushootseed by developing robust language and culture programs that teach our youth and keep our Native language alive.”

In early 2024, Aquarium team members Malik Johnson and Kaitlin Brawley—who help care for giant Pacific octopuses—contacted the students’ teacher Teresa Allen about naming the octopus. The naming process reflects the Aquarium’s aim to further integrate more languages, stories, names, faces and knowledge of the Indigenous peoples we partner with throughout the region. Recent work has also included new signage in Lushootseed, the integration of Indigenous languages into Aquarium camp and youth curricula, presentations that highlight our relationship with Makah waters and other projects that amplify Indigenous languages and traditional ecological knowledge at the Aquarium.

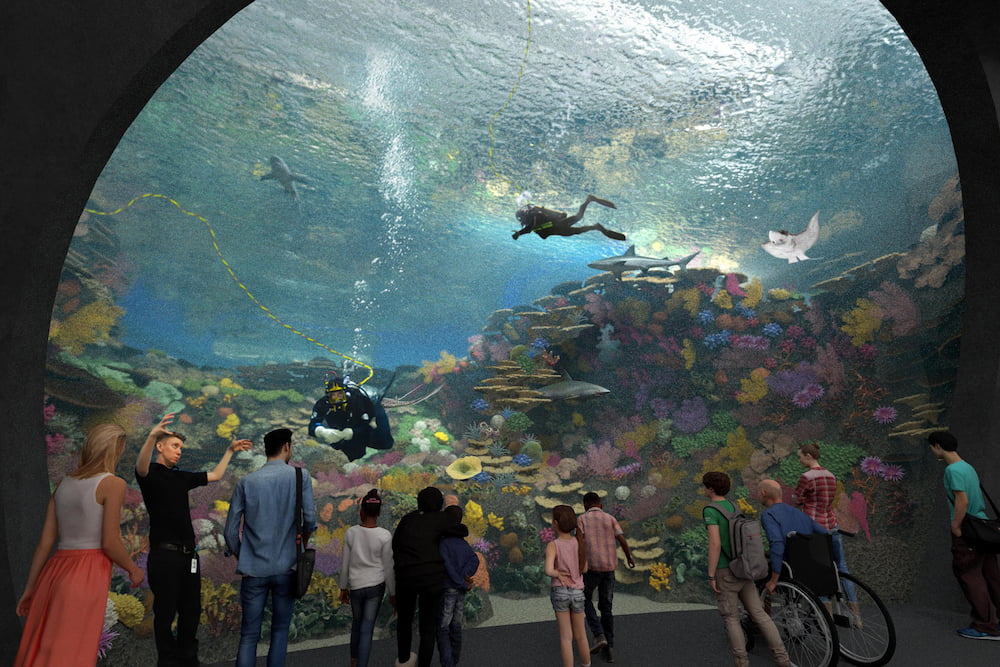

Arrangements are being made for the Muckleshoot Tribal students to visit sqiqələč this fall. Like other giant Pacific octopuses, sqiqələč will live at the Aquarium temporarily. Aquarium divers carefully collect a certain number of octopuses with a special permit from the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife. They typically stay with us for around a year, and when they show signs that they’re mature and ready to mate, our divers return them to their original collection location so they can complete their life cycles and reproduce.

In August, the Aquarium and the Muckleshoot Tribe announced a new partnership to enrich cultural and marine science education work.